He did not try to impose his knowledge and abilities on us. A flock of birds or geese would fly overhead and he would suddenly ask, “How many?” If you saw it once, you had to remember it instantly – that was his system of childrearing. I was supposed to remember after one time the names of streets, buildings, people, transportation, and even which way the wind was blowing when they took me to Orenburg. Leaving an unfamiliar building, I was supposed to describe to him what objects were there and how they were laid out. He himself was very observant. When you walked with him in a crowd, he would say, “Did you see that man who passed? He has a peculiar gait. Do you see this one? He keeps looking around, searching for something.” He noticed all kinds of insignificant details and made me remember everything.

Now it seems unusual to me that from my very childhood, somewhere around nine years old, he taught me to remember everything he said the first time. He used to say, “Remember what I say the first time because it not going to repeat it for you. You have to know this in order not to repeat mistakes and not to tell anyone, or there will be trouble.” Even then I realized that he was concerned not only for us but for other people as well. He used to tell us about them and show us their photographs, saying: “I`m showing you one time. I`m not going to show you again. Remember these people.” But whether or not they were alive at the time, we didn’t know.

Sometimes certain people from some unspecified place would pay him very brief visits. He would go out with them and discuss something with them. We never saw them before or after. We could not get him to tell us who they were or why they had come. He smiled and said nothing. Probably he didn’t want us to know his former life and didn’t want us to expose ourselves or those people to danger. In. the 1960s, my father would write postcards to someone and give them to my younger sisters, who could not read yet, to drop in the mailbox. If we asked him whom the postcards were for and what was written there, he only smiled and said nothing.

He had amazing friends. For example, there was the old man Yavorsky, who lived in our village. Once my father took me along to see him, when I was about nine. There was an old man wearing a belted white peasant shirt lying on the stove. My father suddenly said to him: “Tell me, grandpa, how did Nikolai Ivanovich Kuznetsov die?” The old man raised up onto one elbow and looked at me: “And who’s this with you?” “This is my son; you can talk in front of him.” And then the old man told us about waiting for Kuznetsov with Strutinsky. That was their assignment. He was in the Signal Corps in Poland. They were waiting for him outside Lvov, but he never did come. Then they received the news that Nikolai Ivanovich Kuznetsov had died – he had blown himself up when he fell wounded into the hands of the nationalists. For me what was most interesting is where my father met him. He himself said it was at Uralmash [Urals Machine – Building Factory], where he had been trying to get a job.

Often in our childhood years we would see how lonely he was, despite the fact that he had a wife, our mama, who slaved away indefatigably to raise us. All those years, especially in the 1960s, he spent a lot of time at his radio, listening to “The Latest News” from morning till night. This is when he began telling me about the revolution, politics, and Chamberlain. He was constantly thinking about Kerensky. He knew not only who Kerensky was but for some reason how he had fled and where he lived. He said that Kerensky made himself out to be a leader but in fact was an adventurist. My father would keep returning to the idea that tsars worried constantly about the state, the treasury, and the army, without which there was no state, and watched over their Orthodox Church. He told us how they killed Trotsky in Latin America.

My father was an invalid. (He used to say: “I was born a cripple like this.”) His left foot was withered, size 40, and his right a size 42. Once he said that his foot did not wither until about 1940. He had a curvature of the spine, many scars on his back and arms, and the traces of shrapnel wounds at his waist, under his left shoulder blade, and on his left heel. This evoked puzzled questions from us. The man had never been in a war, but he was so crippled. Where? When? But it was not done to talk about this in our family. Once as a child I saw his wounded back and asked him what had happened. “Well,” he said, “there was a certain business. They were shooting in a basement, killing people.” When I asked him what happened to his foot, he waved his hand and said that if they had cut off his other foot he would have been totally incapable of work. “But this way I can work and earn my living.” His foot always hurt, he had cut himself with a razor somehow on the heel, and he had a terrible scar there. He went especially to Leningrad to buy “general’s boots,” which had a high instep and were sometimes sold in the 1960s. He said that previously he had had an orthopedic insert; they had given him massages, stretched and massaged his foot. He had wanted to have an operation, but he was afraid his heart couldn’t take it, even though he was relatively young.

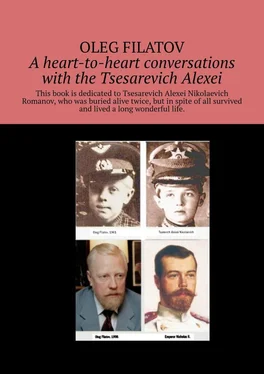

It must be said that he never went to doctors and no certificates of his illness remain. Only once, in 1975, we made him go for a physical. This is the only information we have about the state of his health. By the way, we have never had photographs of my father in his younger years. There are a few from before the war, and those there were had been taken much later. Generally speaking, we have very few documents for him, although he taught us to store every document and every paper carefully and never lose anything. He would tell us that his birth certificate had been lost and so he had had to reconstruct it from the church’s registers. “So it was a dentist who established my age. But he was wrong.” My mother remembers that he confessed to her in 1952 that he was forty eight.

Despite his disability, he possessed stunning endurance. He could go great distances without a stick, favoring first one leg and then the other. He made these treks daily, especially in the summer on his days off, when he walked a couple of miles to the river to fish. He was very strong spiritually and carried himself with the greatest dignity. I don’t remember an instance when he was humiliated by anyone or called an invalid. He himself simply came undone whenever his illness kept him from doing something. This would get discussed and then he would calm down. All his life he did certain special calisthenics and said that without them he would be as skinny as a rail.

Often he would suddenly fall ill. We couldn’t figure out what was wrong, but he never went to doctors. He would put himself to bed and lie there for hours on end. He swallowed certain tablets and was always taking ascorbic acid. When I would ask him what was wrong with him, he would answer: “I got this from my parents. And I was left a cripple my whole life. People said my parents should not have married, but they did and gave birth to me the way I am.” When he was in pain from being hit by something in the foot, he would bandage up the bruise and put himself to bed or sit hunched over, muttering something nonstop. Once I heard him repeating the Our Father. This was his defense. He used to say: “There couldn’t be anything more terrible in life. The most terrible thing of all is theIpatievcellar.” Of course, these phrases sank into our minds.

Usually he got up early, did his calisthenics, splashed himself with cold water, and always shaved very carefully. This amazed me and I would ask, “Papa, what are you, a soldier?” He would answer: “No, but my ancestors were all soldiers.” He was painstaking and neat about his apparel, and if he was going anywhere, then the packing was an entire process. He went off to work with dignity, and we saw that this was his principal business. After I was 16, he began having me lift weights and dumbbells. In the summer I loved to swim and did this very well. He told us it was easiest of all to swim on your back or do the butterfly, if you didn’t make noise.

Читать дальше