Frank Bellew - The Art of Amusing

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank Bellew - The Art of Amusing» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Art of Amusing

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40309

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Art of Amusing: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Art of Amusing»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Art of Amusing — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Art of Amusing», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Did we know what a million meant?"

To which we promptly replied that a million meant ten hundred thousand.

"Did we know what a billion meant?"

A billion, according to Webster, was a million million.

A light twinkled out of the gold spectacles, and a glow suffused the expansive forehead, as, with a certain playful severity, he propounded the following:

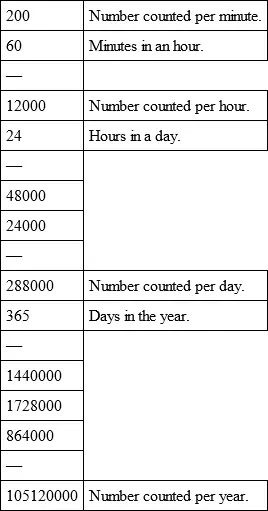

"How long would it take you to count a million million, supposing you counted at the rate of two hundred per minute for twenty-four hours per day?"

We replied, after a little reflection, that it would take a long time, probably over six months.

With a triumphant air, the gold spectacles turned to our friend Nix. Nix, who is a pretty good accountant, thought it would take nearer six years than six months. One young lady, who was not good at figures, felt sure she could do it in a week. Gold Spectacles exhibited that intense satisfaction which the mathematical mind experiences when it has completely obfuscated the ordinary understanding.

"Why, sir," he said, turning to us, "had you been born on the same day as Adam, and had you been counting ever since, night and day, without stopping to eat, drink, or sleep, you would not have more than accomplished half your task."

This statement was received with a murmur of incredulous derision, whilst two or three financial gentlemen, immediately seizing pen and paper, began figuring it out, with the following result:

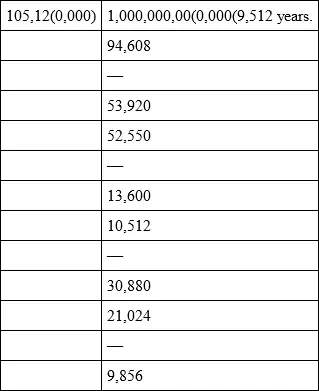

From this calculation we see that by counting steadily, night and day, at the rate of two hundred per minute, we should count something over one hundred and five millions in a year. Now let us proceed with the calculation:

So that it would take nine thousand five hundred and twelve years, not to mention several months, to count a billion. Gold Spectacles chuckled visibly, and for the rest of the evening gave himself airs more worthy of a conquered Southerner than a victorious mathematician. He afterwards swooped down upon and completely doubled up a pompous gentleman bearing the cheerful name of Peter Coffin, for making use of the very proper phrase, "As clear as a mathematical demonstration."

"That may not be very clear, after all, Mr. Coffin," said Gold Spectacles.

"How is that, Mr. Sprawl (Gold Specks' proper name being Sprawl); can anything be clearer than a mathematical demonstration?"

"I think, sir," answered Mr. Sprawl, "I could mathematically demonstrate to you that one is equal to two. What would you think of that, sir?"

"I think you couldn't do it, sir."

Thereupon Mr. Sprawl took a sheet of paper and wrote down the following equation – the celebrated algebraic paradox:

Mr. Coffin examined it carefully standing up, and examined it carefully sitting down, and then handed it back, saying that Mr. Sprawl had certainly proved one to be equal to two. The paper was passed round, and those learned enough scrutinized it carefully. The demonstration all allowed to be positive, yet no one could be made to admit the fact .

Here a certain married lady avowed her great delight in knowing that one had at last been proved equal to two . She had been for years, she said, trying to convince her husband of this fact, but he always obstinately refused to listen to the voice of reason. She now trusted he would not have the effrontery to fly in the face of an algebraic paradox .

Seeing the talk had taken an arithmetical turn, and was moreover getting fearfully abstruse, our friend Nix thought he would gently lead the tide of conversation into some shallower channel, wherein the young ladies might dabble their pretty feet without danger of being swept away in the scientific torrent. To this end he submitted the well known problem: "What is the difference between six dozen dozen and half a dozen dozen?" Strange to say, no one present had ever before heard of it, but the best part of the joke consisted in Mr. Sprawl being completely taken by it.

"Why, they are both the same," he answered promptly.

All the rest seemed to think so too, and some could not get into their heads, although poor Nix spent half an hour trying to convince them, that half a dozen dozen was the same thing as six dozen, or 72; whilst six dozen dozen must of course be seventy-two dozen, or 864.

While Nix still spoke, a handmaiden appeared, bearing tinkling cups and vessels of aromatic tea (not the weak green kind, bear in mind), and plates of sweet cookies and toast, and then bread and butter, and steaming waffles, and divers and sundry other delicacies known to true housewives and good Christian women, who love their fellow-creatures and respect their organs of digestion.

As the tea is being served, we walk up to a young gentleman and ask him if he knows why the blind man was restored to sight when he drank tea. The young gentleman gave it up precipitately.

"Because he took his cup and saucer (saw sir)."

The gentleman in gold spectacles says something about our being a sorcerer , but we heed him not, fearing he may put us through another algebraic paradox. Then comes a general demand for the answer to the charade we published in our last chapter, which commenced:

"My whole is the name of a school-boy's dread."

"The answer to this, ladies, is Rattan; and you will find it," said we, "a most excellent charade for children."

Now commenced a grand festival of puzzles and riddles. Specimens of all kinds were trotted out for inspection, from the ponderous construction of our ancestors, commencing in some such style as, "All round the house, through the house, and never touching the house," etc., to the neatly turned modern con.

Our friend Nix asked why Moses and the Jews were the best-bred people in the world?

Another wished to know why meat should always be served rare?

Both these individuals, however, refused to give the solution until the next meeting of the assembled company. Others were more obliging, but as their riddles were mostly old friends, somebody knew the answers and revealed them. It is a mistake to suppose that a good thing ought not to be repeated more than once. There are certain funny things that we remember for the last twenty years, and yet we never recall them without enjoying a hearty laugh. We have read Holmes's Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table once every six months, ever since it was published, and enjoy it better each time. We have been working away at the Sparrowgrass Papers for years, and yet we raise just as good a crop of laughter from them as ever. These books resemble some of our rich Western lands: they are inexhaustible. So when one of the company asked, "When does a sculptor die of a fit?" we waited quietly for the answer, "When he makes faces and busts," and laughed as heartily as though it were quite new, although we had been intimate with the old con ever since it was made, some fifteen years ago. We even enjoyed the time-honored riddle: "What was Joan of Arc made of?" "Why, she was Maid of Orleans, of course." But then this was put by a seraph with amber eyes, and a very bewildering way of using them. The success attending this effort seemed to stimulate the gentleman in gold spectacles, who rushed into the arena with the inquiry: "What was Eve made for?" Most of us knew the answer well enough, but we waited politely to let him deliver it himself. Our surprise may be readily conceived when he informed us, with evident glee, that "she was made for Harnden's Express Company." Some looked blank, and others tittered, whilst Nix explained to the ladies the true solution. It was for Adam's Express Company that Eve was made. After this followed in quick succession a shower of riddles, some of them so abominably bad, that an old gentleman, who did not seem to take kindly to that sort of amusement, gave the finishing-stroke to the entertainment by the annexed:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Art of Amusing»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Art of Amusing» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Art of Amusing» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.