Ariana Franklin - Mistress of the Art of Death

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ariana Franklin - Mistress of the Art of Death» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mistress of the Art of Death

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Mistress of the Art of Death: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mistress of the Art of Death»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

From The Washington Post

It's hard enough to produce a gripping thriller – harder still to write convincing historical fiction that recreates a living, breathing past. But this terrific book does both, and does it with a cast of characters so vivid and engaging that you'd be happy to read about them even if they weren't on the track of a sexually depraved serial child-murderer.

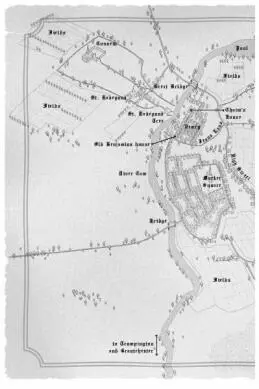

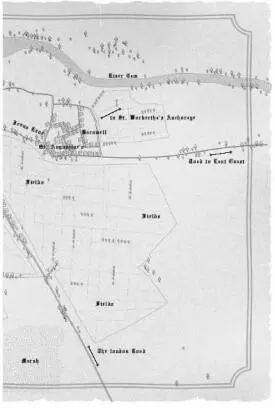

Mistress of the Art of Death opens with a clever takeoff on Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, which introduces the central players, a group of pilgrims returning from the shrine of the newly canonized St. Thomas à Becket: a prior and a prioress (from rival abbeys); two knights, lately returned from the Crusades; an overweight but very shrewd tax collector; a gaggle of citizens; and three Gypsies, who are in fact secret investigators sent by the king of Sicily to discover the truth behind a series of gruesome murders near Cambridge.

Four children have been found dead and mutilated. The Jews of Cambridge have been blamed for the murders, the most prominent Jewish moneylender and his wife have been killed by a mob, and the rest of the Jewish community is shut up in the castle under the protection of the sheriff.

As the only group allowed to commit usury – that is, to lend money at interest – the Jews are prosperous, and thus the king of England considers them his prize cash cows. He wants them cleared of suspicion and released, so they can go back to paying him high taxes. To this end, he appeals to his cousin, the king of Sicily, to send his best master of the art of death: a doctor skilled in "reading" bodies. Enter Vesuvia Adelia Rachel Ortese Aguilar, 25, the best mistress of death that the medical school at Salerno has ever produced. With Simon of Naples, a Jewish "fixer," and Mansur, a eunuch with a mean throwing-ax, it's her job to find a murderer before he – or she – can kill again.

Adelia comes onstage when she meets the prior under dramatic circumstances on the road, saving him from a burst bladder caused by a swollen prostate by thrusting a hollow reed up his penis. Not every man would follow up on an introduction like this, but the prior wants the mystery solved, too – and if the solution happens to ace out the rival abbey, so much the better.

Adelia finds 12th-century England a barbarous place. England finds Adelia a jaw-dropping anomaly. And Franklin exploits the contrast brilliantly. We're on Adelia's side from the start, identifying with her quite modern sensibilities – but at the same time, as she begins to know the English inhabitants as people, we sympathize with them, too. And a small but nice romantic subplot develops as the celibate, married-to-science Adelia discovers to her horror that live bodies have minds of their own.

Though the story is set in Cambridge, the Crusades run through the culture. We see both the corruption and the idealistic faith of the period, and while the Jews come off by far the best, Christians and Muslims are portrayed with evenhanded understanding. Beyond this, the story's background is a wonderful tapestry of the paradoxes and struggles of the times: Christianity and Islam, Christians and Jews, science and superstition, and the new power of Henry II's rule of law versus the stranglehold of the Church.

There are also fascinating details of historical forensic medicine, entertaining notes on women in science (the medical school at Salerno is not fictional), and a nice running commentary on science and superstition, as distinct from religious faith. Franklin does this subtly, by showing effects, rather than by beating us over the head with her opinions. These are clear enough but expressed with artistry rather than political correctness.

Franklin likewise balances cynicism, humanity and objectivity well. Adelia feels horror, fury and sympathy on behalf of the victims and the bereaved, but she doesn't let that get in the way of finding the truth. And the story makes it clear that the motives of those who want a solution to the crime are not necessarily purer than the motives of those who want to conceal it.

Mistress of the Art of Death is wonderfully plotted, with a dozen twists – and with final rabbits pulled out of not one hat but two, as both the mystery and the romance reach satisfactorily unexpected conclusions. It's a historical mystery that succeeds brilliantly as both historical fiction and crime-thriller. Above all, though, Franklin has written a terrific story, whose appeal rests on the personalities of the all-too-human beings who inhabit it.

– Diana Gabaldon, author of a series of historical novels, including "Outlander" and "A Breath of Snow and Ashes."