4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

First published as Birds Art Life in Canada by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited in 2017

First published as Birds Art Life in the United States by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc in 2017

Copyright © Kyo Maclear 2017

By association with Westwood Creative Artists Ltd.

Illustrations (interior and jacket): Kyo Maclear

Photography: Jack Breakfast ( www.smallbirdsongs.com), unless otherwise indicated

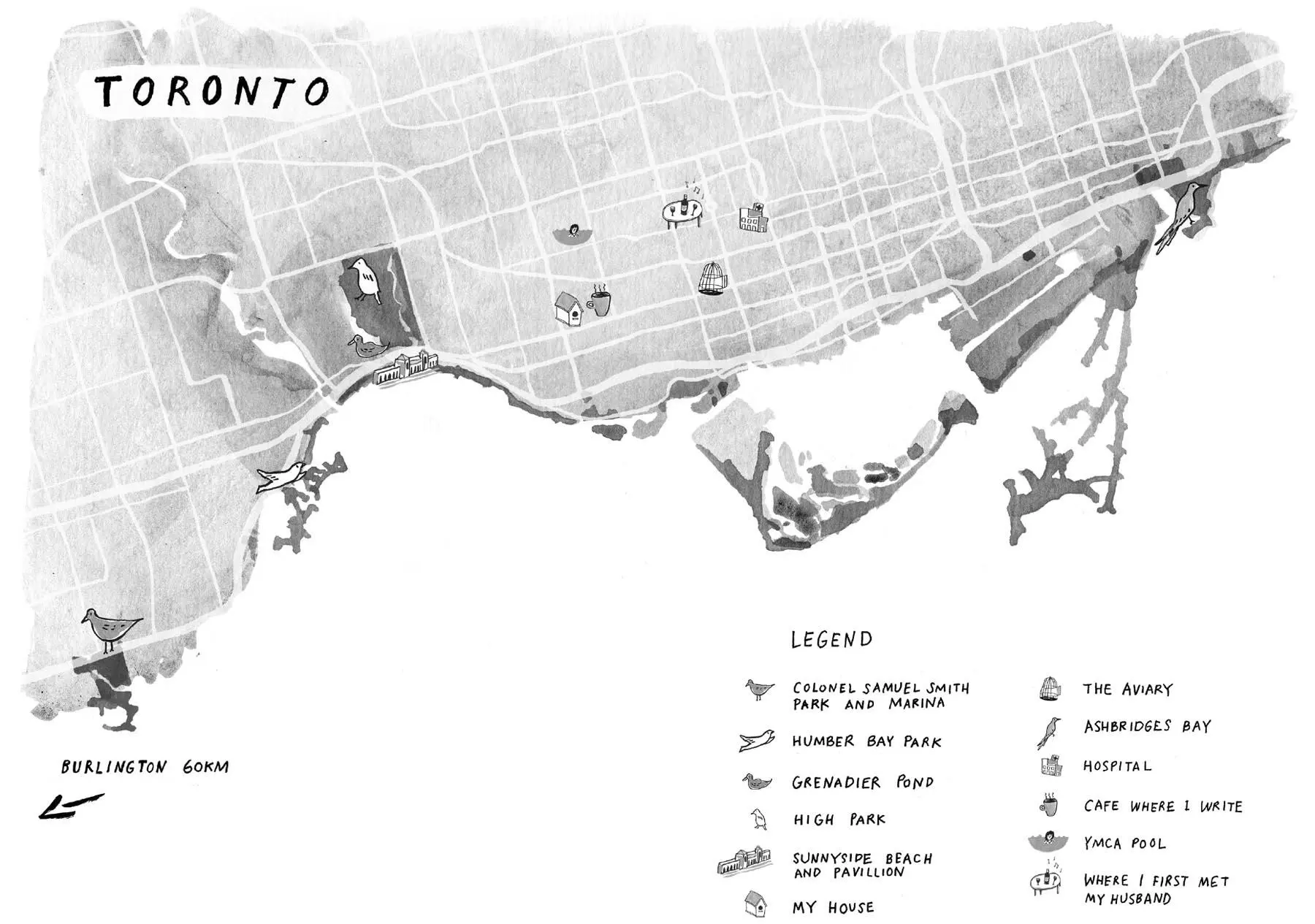

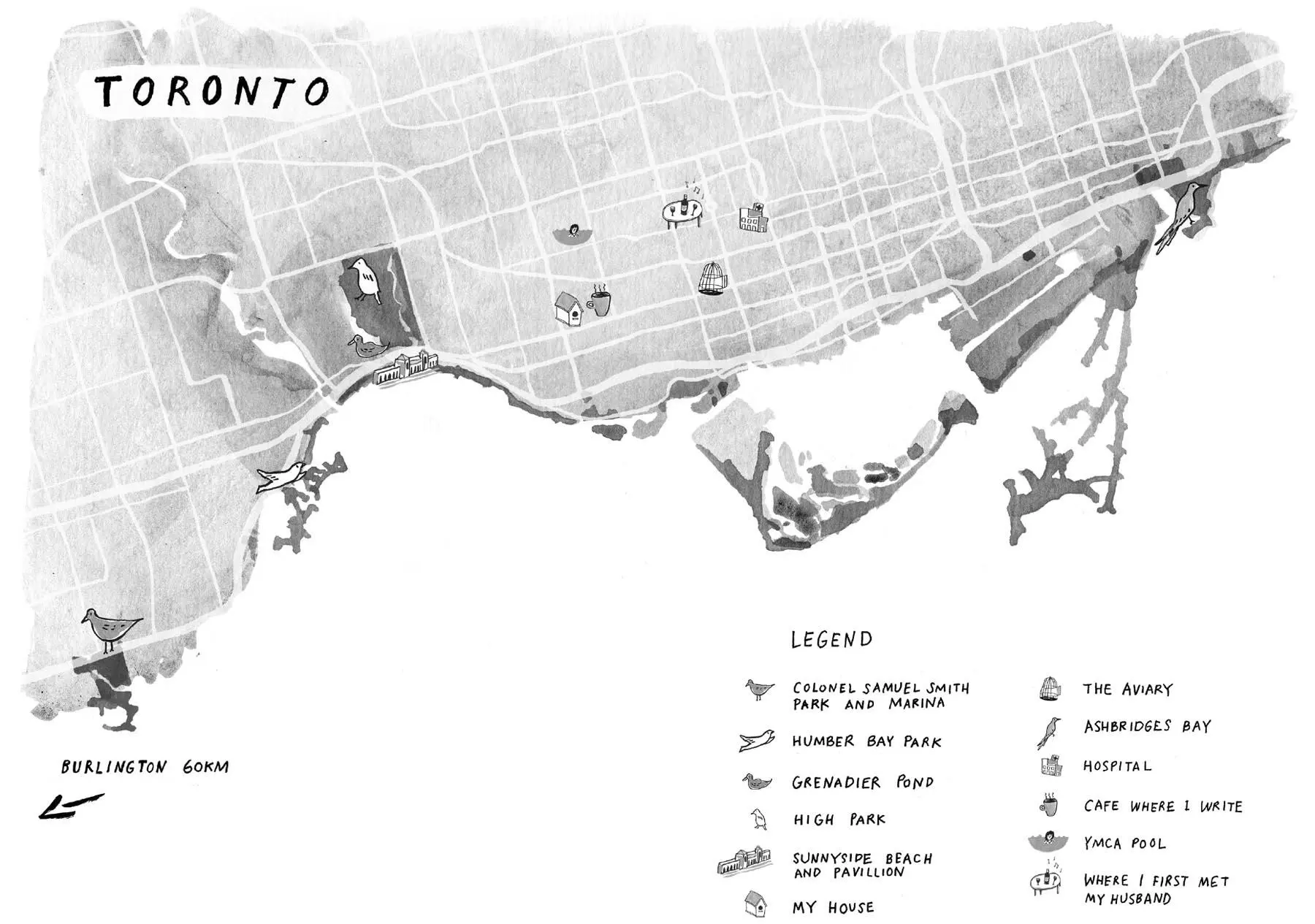

Map: Jennifer Griffiths

Book design: CS Richardson

The right of Kyo Maclear to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008225049

Ebook Edition © 2018 ISBN: 9780008210014

Version: 2017-11-06

For David

Someone has put cries of birds on the air like jewels.

ANNE CARSON

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

WINTER

Prologue

December: Love

January: Cages

February: Smallness

SPRING

March: Waiting

April: Knowledge

May: Faltering

SUMMER

June–July: Lulls

August: Roaming

AUTUMN

September: Regrets

October: Questions

November: Endings

WINTER

December: Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Permissions

About the Publisher

On facing a father’s illness

and finding that grief takes strange forms,

including wanderlust.

One winter, not so long ago, I met a musician who loved birds. This musician, who was then in his mid-thirties, had found he could not always cope with the pressures and disappointments of being an artist in a big city. He liked banging away on his piano like Fats Waller but performing and promoting himself made him feel anxious and depressed. Very occasionally his depression served him well and allowed him to write lonesome songs of love but most of the time it just ate at him. When he fell in love with birds and began to photograph them, his anxieties dissipated. The sound of birdsong reminded him to look outwards at the world.

That was the winter that started early. It snowed endlessly. I remember a radio host saying: “Global warming? Ha!” It was also the winter I found myself with a broken part. I didn’t know what it was that was broken, only that whatever widget had previously kept me on plan, running fluidly along, no longer worked as it should. I watched those around me who were still successfully carrying on, organizing meals and careers and children. I wanted to be reminded. I had lost the beat.

My father had recently suffered two strokes. Twice—when the leaves were still on the trees—he had fallen and been unable to get up. The second fall had been particularly frightening, accompanied by a dangerously high fever brought on by sepsis, and I wasn’t sure he would live. The MRI showed microbleeds, stemming from tiny ruptured blood vessels in my father’s brain. The same MRI revealed an unruptured cerebral aneurysm. An “incidental finding,” according to the neurologist, who explained, to our concerned faces, his decision to withhold surgery because of my father’s age.

During those autumn months, when my father’s situation was most uncertain, I felt at a loss for words. I did not speak about the beeping of monitors in generic hospital rooms and the rhythmic rattle of orderlies pushing soiled linen basins through the corridors. I did not deliver my thoughts on the cruelty of bed shortages (two days on a gurney in a corridor, a thin blanket to cover his hairless calves and pale feet), the smell of hospital food courts, and the strange appeal of waiting room couches—slick vinyl, celery green, and deceptively soft. I did not speak of the relief of coming home late at night to a silent house and filling a tub with water, slipping under the bubbles and closing my eyes, the quiet soapy comfort of being cleaned instead of cleaning, of being a woman conditioned to soothe others, now soothed. I did not speak about the sense of incipient loss. I did not know how to think about illness that moved slowly and erratically but that could fell a person in an instant.

I experienced this wordlessness in my life but also on the page. In the moments I found to write, I often fell asleep. The act of wrangling words into sentences into paragraphs into stories made me weary. It seemed an overly complicated, dubious effort. My work now came with a recognition that my father, the person who had instilled in me a love of language, who had led me to the writing life, was losing words rapidly.

Even though the worst of the crisis passed quickly, I was afraid to go off duty. I feared that if I looked away, I would not be prepared for the loss to come and it would flatten me. I had inherited from my father (a former war reporter/professional pessimist) the belief that an expectancy of the worst could provide in its own way a ring of protection. We followed the creed of preventive anxiety.

It is possible too that I was experiencing something known as anticipatory grief, the mourning that occurs before a certain loss. Anticipatory. Expectatory. Trepidatory. This grief had a dampness. It did not drench or drown me but it hung in the air like a pallid cloud, thinning but never entirely vanishing. It followed me wherever I went and gradually I grew used to looking at the world through it.

Читать дальше