Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"If ever you cared to come, I'm certain they'd give you a ticket."

"That's very kind of you." She shook her head, smiling. "But I'm afraid it would be wasted on me. I don't understand music."

"Neither do I." His sudden exasperation made Lily smile. "But that needn't prevent your coming if you'd like to."

"I don't think I will, thank you, darling. I very seldom go out in the evenings now."

Yes, actually, he could swear that it had amused her to break through his carefully and painfully prepared armour. His armour of politeness, mildness, dullness. She said very sweetly:

"You'll give my love to Mary, won't you, when next you're there? I haven't seen her for ages. Tell her that any time she cares to, I should be delighted to have her to tea. But, of course, I know she's very busy." Lily was helping Eric on with his overcoat. "I've nothing very important to do myself"—she suddenly uttered a quiet laugh— "and so I always feel I may be rather apt to forget how hard other people in the world are working."

She came with Eric across the little hall to the door of the flat. Her manner changed.

"I hope your landlady feeds you properly?"

"Of course she does," he forced himself to smile.

"And doesn't put all sorts of ridiculous extras on your bills?"

"No."

"Well, good-bye, darling."

"Good-bye, Mother."

He stooped and kissed her cheek. Had an impulse to bolt down the stairs. Rang for the lift.

Out in the street, walking fast, he thought dully: Why do I come here? What makes her wish to see me?

She can trifle with all this, he thought, in a sudden gust of anger. It costs her nothing. She doesn't feel. For her this is only pleasant, sad. It's a sentimental luxury.

No, he thought, that's utterly unjust. I'm a brute. I'm vile to her.

Darling Mother. Can't I help her? Must we go on like this? It seems so miserable and senseless. His mind ranged for solutions, followed the old circle. No, there's nothing.

Nothing, nothing, he thought—seeing a tram, people shopping. Sane women with baskets choosing fish, or materials for curtains. Sensibility is an invention of the upper class, he had read, had said. Suppose one explained everything to that policeman. Don't get on with yer Ma, eh? After all, some of it could be translated into that language. But he would expect a black eye to be shown him, or a bruise inflicted by a poker.

It was a lovely afternoon. He had vaguely intended a walk in the Park. But bright, clean Kensington, with its nursemaids and old ladies, so prim and cosy and well-to-do—no, Eric was still haunted by the memory of a Welsh village. The strangely compact blocks of cottages, like the keyboard of a piano, mounting the hill. The sombre' and motionless headgear of the pits. Men lounging in groups at corners. The rain-drenched landscape. The grey sodden sky. No, he must do some sort of work. He'd go back to his rooms in Aldgate and write a few more pages of his report. Later, he might see how they were getting on with the new room at the Boys' Club. And he'd promised his friend the probation officer to see if he could trace an ex-reformatory boy whom they'd got a job as boots in" a commercial hotel and who'd disappeared. His uncle, who lived somewhere in the neighbourhood of Hackney Marsh, might know where he was.

V

Edward Blake stood for a moment at the corner under the lamp-post, swaying gently on his toes. Behind him, the Tiergarten lay inky black. Patches of snow gleamed bluish round the feet of the bare trees. In the Sieges Allee the lights shone brilliant and hard as diamonds upon the icy array of statues. It was much colder than the North Pole.

Edward didn't feel the cold. He started forward again, his overcoat flapping loose around him, singing to himself. He was beautifully warm all over, and the thing which kept whizzing round in his head gave him a pleasant sensation of deafness which was in itself a kind of warmth, blunting the edges of the freezing outside world. For quite considerable distances he walked almost straight— then suddenly he made an erratic swerve, wandering to the brink of the roadway or stumbling up against the steps of a statue. Whenever he did this, he saluted or said: Excuse me.

Edward knew the statues well. Heinrich das Kind was of course his favourite, but Karl IV. was

the one he really liked. Karl and he had something in common. Karl always looked as though he'd seen something particularly fetching on the other side of the road. When Edward reached him, he sat down for a little on the steps. Then he got up and wandered on.

"Well," said Edward, aloud, but not addressing the statues, "here I am, you see." For it had suddenly struck him—how queer; ten years ago I wasn't allowed to come down this road. Now it's allowed again. And in ten or twenty years' time perhaps it won't be allowed. How bloody queer. In 1919 we were going to have bombed Berlin. Mathematically speaking, there's no reason why I shouldn't be dropping a bomb on myself at this very moment.

Somehow or other he got across the Kemper Platz without being run over. He had a curious feeling, as though he weren't allowed to look either to the right or the left, was in blinkers.

He'd been walking for hours and his feet were tired. He'd been right up in Pankow and down through Wedding. He'd stopped at least twenty or thirty times for drinks. Well, he was nearly home now. In the Potsdamer Platz an omnibus bore suddenly down upon him, seeming to swim out of the darkness, waving its lighted fins. He had to jump for the pavement. Why, I might have been killed, he thought—and this was really extremely comic.

His hotel was in aside street behind the Anhalter

Bahnhof. Edward steadied himself, said Guten Abend to the girl in the office, took his key from the hook. He met nobody on the way up to his room. At this time, early in the evening, the place was very quiet. He flung open the door. It banged against the foot of the bed.

How extraordinarily bright the electric light was. Its reflection flashed from the mirror of the wardrobe and from the mirror over the monumental washstand. The room was warm. Too warm. Edward sat down on the bed. The brightness of the light made him dizzy.

He rose and opened his suitcase, which stood on a chair. Yes, they were there all right. The two envelopes lay on top of his folded clothes. He took them out. Miss Margaret Lanwin. Eric Vernon, Esq. He opened Margaret's first. Three pages of it. How beautifully it's written, Edward thought. How bloody lucky I wrote it while I was still sober. Dear Margaret—By the time you get this I hope you'll be thinking a little better of me than you do at present.

Damn these explanations. And they'll read it all out in court. I could post it now, though. No, Edward decided, sitting down on the bed, I can't be bothered. He tore the letter up slowly. But perhaps they'll find the pieces and stick them together. The Germans are said to be a patient race. Better burn them. He went over to the washstand for the soap-dish, dropped the pieces into it and

set fire to them. Then he carefully took the ashes, opened the window and scattered them out. Better clean the soap-dish too. It might be a clue. While he was cleaning the soap-dish, he dropped it. It broke in three pieces. Oh hell, thought Edward. But it'll go on the bill. I suppose somebody'll pay the bill.

He opened the other letter:

"Dear Eric,

At my Bank there is a small black metal box. Will you see that all the papers inside it are destroyed?

I am asking you to do this because you are the only person I can trust.

I am leaving you some cash for your funds. Spend it as you think best. Edward."

Yes, that was all right. He put it back in the suitcase and closed the lid. Should he lock it? No. That would only make extra trouble.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

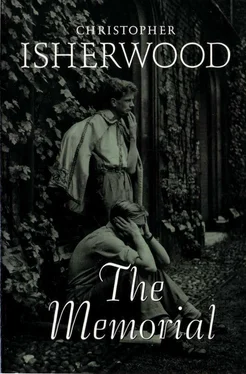

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.