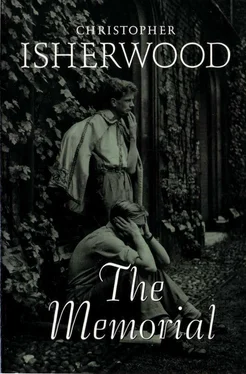

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She wore grey today, not black. And this seemed exactly to suit the mood of the sad, cloudy afternoon and the abandoned rooms of the mansion, where chandeliers hung from moulded ceilings, draped in holland bags. Their visit was somehow like a religious ceremony, and their eyes met with the expression of people who regard each other for a moment in church. The caretaker's voice echoed dully down the corridors. Ronald and Mrs.Vernon addressed each other occasionally, in low voices, remarking on a piece of china or the back of a chair.

At length, when they stood looking out over the lawn from a window on the second storey, she said:

"I can't bear to think of all this passing away."

There was real emotion in her voice. It moved Ronald deeply.

"People want to destroy all this," she said. "But what have they got to put in its place?"

The courage of her reactionary romanticism

moved him. He was a reactionary himself, perhaps, but, reading the newspapers, he had felt a confused enthusiasm also for housing schemes, playing-fields, London as a garden city. He belonged to both camps. She did not. He honoured her for it. Standing at the window, in the waning afternoon, with her slight figure, her low voice, she seemed to be crying out against that distant stream of scarlet buses and dark closed cars sweeping by the gates. She challenged the future with an extraordinary passion of quiet resentment. There were tears in her eyes.

"They've got nothing," she said.

He mumbled some words of agreement.

Mrs. Vernon seemed pleased at his support. She smiled sadly and yet gaily.

"At any rate, they've got no use for us."

III

Coming down the gas-lit mews with three beer bottles under her arm, Mary experienced, as often before, a pang of love for her home. My dear little house, she thought. It was full of people. The front door stood ajar. Lights shone from all the windows. Odours of fish-pie met her as she set foot on the stairs—which were really only a very steep step-ladder covered with linoleum. Mary had once tripped and slid down them on her seat, shooting right out into the mews and the presence of several astonished chauffeurs, clutching a new loaf.

"You've left the door open, Earle," called Margaret's voice from above; "somebody's got in."

They peeped down at her:

"Oh, it's only you, dearie. We were afraid it was more uninvited guests. There's enough of us as it is."

"And to think," said Mary," of your poor old Ma running all the way from the Goat in Boots because you'd left your key behind. I thought the music-room window was bolted."

"So it was, but that didn't deter our Maurice. He climbed the drain-pipe."

Maurice, in shirt-sleeves, waiting for Anne to tie his evening tie, grinned.

"Look here, my Tad, you know I don't like my sanitary system to be used for your gymnastic displays."

They all helped to lay the table, pushing past each other in the narrow doorway, each carrying a single fork or a plate.

"Oh, children," said Mary, "it's very kind of you to help Mother, but, you know, I could get the whole job done in two minutes alone."

"That's all right. Just you sit down and rest, Granny dear. Somebody get Mary her Bible and her cashmere shawl."

"I say, we just must subscribe for one. Wouldn't it be too suitable for the Gallery? She'd be exactly like those dear old pets one sometimes sees in ladies' cloak-rooms."

Earle came out of the kitchen:

"Say, if you don't eat your pie soon, Mary, I guess there'll be nothing left but the fish-bones."

"Oh, Earle," said Margaret, "you mustn't guess so much, my dear, really. It simply is not done. In this country we confine ourselves to the direct statement."

"Oratio Recta," said Maurice.

"Oratio what did you say?"

"Oratio Recta."

"I don't think I like that expression at all."

"Where's Eric," Mary asked, "and Georges?"

"Eric rang up to say he might be late," said Anne. "He's got to go to a committee meeting. He says he'll probably take a sandwich and eat it on the bus."

"And Georges isn't quite comfortable about something in the Hindemith."

Sure enough, Mary could hear the sound of a violin coming up from underneath the stairs. There was a stove near the coal-hole door and Georges liked sitting with one leg on either side of it and practising.

"He's scared stiff," said Maurice.

"He's not half so scared as I am," said Earle.

"I expect you'll forget your Debussy in the middle and have to play 'Mary Lou'."

"Nobody would notice."

"Don't you get being so nasty, my boy," said Mary. "You ain't got no call ter be so bitter at your time of life, and you so 'andsome."

"I think Oldway would notice," said Margaret. "He'd write that Mr. Gardiner's tempo left much to be desired."

"Now, children," said Mary, "we must eat. Maurice, don't be a pig. If you're too proud to have your dinner with us, you can leave ours alone."

Maurice was at his usual trick of sampling the food. He licked his fingers.

"Yes, I'll pass that. But it's not so good as the

one we had when Edward was here. He's easily the best fish-pie maker we've got."

"You might tell Georges we're ready," said Mary to Anne, glancing quickly—she couldn't help it—at Margaret's face.

"Heavens, I must wash," said Margaret. "I'm simply filthy."

Eric sat at the card-table, murmuring:

"Only members sign. Please give up your guest-tickets inside the door."

Rich old ladies in black silk, with veils, assisted by artistic nieces, passed along the passage into the concert-room, complaining of the stairs.

"My dear, are you sure this is the place?" one of them asked, with distaste.

Lady Croker, always rude, said that the passage was too narrow. The headmistress of a large girls' school gushed to Eric:

"We're sure this is going to be a real treat."

An elderly colonel, sent by his wife, came out to complain that members were keeping as many as three seats for friends and putting mackintoshes on them. A small newly joined member couldn't believe that one was allowed to sit wherever one liked. Two or three men lingered by the door, waiting for their chance to ask Eric where the lavatory was. A flustered lady wanted to know:

"Can you tell me, will my membership card and

these three guest-tickets cover the next three concerts, if I bring a friend who had a half-season ticket last year but couldn't use it?"

Eric had to deal with all these people. Sometimes he referred them to Mary, who was standing just inside the door. He could hear her strong reassuring voice, soothing all these unhappy creatures, promising everything, anything:

"Oh, yes, I'm sure that'll be perfectly all right."

Students came from the Royal College, bringing gaudy cushions, knowing that they were too late for the deck-chairs. Pale cultured Jews, rich amateurs. An Oxford don. The critics, with peevish frowns of predisposed boredom, treading on, other people's toes. A few millionaire bohemians, in suits of rough, baggy, expensive tweed. A French teacher of languages. A famous actress. A chemistry master from a public school. Fragments of talk:

"Yes, the Upper Sixth are doing The Merchant of Venice this term."

"Roy scored in the last seven minutes. At the end, I simply couldn't talk above a whisper." ,

"Oh, but you missed something if you didn't see the private rooms upstairs."

And now they were mostly inside. The chatter had died down. Clapping. Beginning of a Bach partita. Eric pushed open the door and came quietly into the concert-room. Mary made room for him in her corner, at the back. The concert-room was the Gallery. Bright canary-coloured nudes in stockings on striped sofas hung round the walls, alternating with rather scratchy still life, a plate of gritty-looking bananas or a knife, a folded copy of Le Matin, one kid glove. The rigged-up stage was backed by sackcloth curtains. Georges' huge body dwarfed the little violin, like an enormous mechanical appliance required to perform a very delicate and minute task. He held it with grotesque tenderness, like a baby, his double chin doubled against it. Earle, when he came on to play the Debussy Preludes, was very nervous. He sat down in a rapid, preoccupied manner and started without waiting for any applause, as though he'd just hurried back from answering the telephone to resume work. What a noise he could make! "I didn't know he had it in him," Mary whispered to Eric, at the end of the second piece. "The only question is: will the platform stand it? We ought to have lashed the piano down with ropes."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.