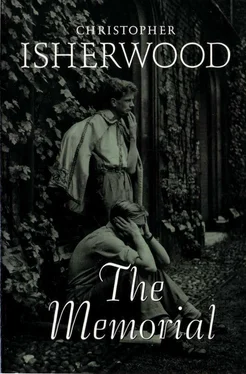

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

BOOK TWO 1920

I

Lily, with her feet up on the chintz window-seat, her cheek resting against the oak shutter, thought: How tired I am. How terribly tired.

It was past eleven, already. Kent, on the box of the victoria, drove round and round the sundial like a clock. The August morning was warm and heavy and moist. The elm-tops were steamy. The atmosphere was drowsy with inaudible vibrations of the distant mills.

Lily thought: It will be like this always. Until I die.

From right across the valley, overlooked by the other window of her bedroom, at the back of the house, sounded the thin wild mournful whistle of a train. A pang caught at Lily's throat and her eyes filled with fresh tears. I ought to be glad to think of dying, she thought. This moved her. She uttered a sob, but others did not follow. She wiped her eyes. Almost immediately she had put away her handkerchief, more tears began to trickle down her face.

This year she had taken more and more to crying when alone. It was becoming easy, a habit. She knew this and must stop. Somebody, or several people, had told her to be brave. Be brave, she repeated to herself. But now that word had no meaning. It sounded rather idiotic. Why should I be brave? Lily thought. Who cares whether I'm brave or not? I'm all alone. Nobody understands or cares. She let the tears stand in her eyes, run down her cheeks, spill into her lap. While the War was still on it had been different. She could be brave then. While the War was still on her grief had had some meaning. She was one of thousands. They seemed to be encouraging each other, standing together. There was patriotism and hatred. You saw cartoons in newspapers and posters on walls. Lily reminded herself that all these mothers and widows, or nearly all of them, were alive today. But they no longer counted. No, we're done with now, she thought. There's another generation already.

And at the thought of this new generation, so eager for new kinds of life and new excitement, with new ideas about dancing and clothes and behaviour at tea-parties, so certain to sneer or laugh at everything which girls had liked and enjoyed in nineteen hundred—at that thought Lily felt not a pang of sadness but a stab of real misery. She was living on in a new, changed world, unwanted, among enemies. She was old, finished with. She remembered how, in schoolroom days, she and a

friend had giggled at their middle-aged governess.

"You must try to live for your boy," somebody had written. Darling Eric, thought Lily mechanically. She always thought of Eric as darling, and her voice, saying the word, was almost audible to her. People didn't understand in the least. How on earth am I to live for Eric, thought Lily, when he's away at school eight months of the year? He was so young, too, when Richard was killed. We could never share this together.

She tried, all the same, to remember fresh scenes of Eric's childhood and boyhood. She saw him running about the garden on a day like this, five years old, in his red jersey and little spectacles. Poor Eric. Poor darling. He was always so plain. He didn't in the least remind one of Richard. Perhaps he was a little like dearest Papa. Lily smiled tenderly to herself and glanced out of the window. But the cockade of Kent's shining black top-hat still moved round and round the sundial. They would all be late. And then she had another memory of Eric, in his preparatory school Norfolk suit, with his new bicycle and another pair of spectacles, really hideous ones, made so as hot to mark the bridge of his nose.

Of course darling Eric would be the greatest joy to her always and the greatest comfort. And every year he would be older and more able to be a companion to her. But the word "companion"

stabbed through her again. A person who held your knitting. That's not life, Lily cried out to herself. That's not life; people being kind to you and talking in gentle voices, trying to think of things which will amuse you. That's not life. She got up, and, walking towards the other window, looked out across the valley at the hills towards Yorkshire and the chimney of the bleaching works by the river and the eye-sore, the new sanatorium for consumptive children from the Manchester slums. "That eye-sore," she called it fiercely, to her father-in-law, who, as usual, grunted. But my life is over, Lily thought.

Perhaps from this very room the Vernon girl of the story had seen her lover drown. Two tiny figures in the valley below. She must have had a telescope. No, it was absurd. The tall stalk-like chimney trailed a long wavy smudge of smoke across the sky. Turning away from that view, so terribly nostalgic, Lily faced her bedroom, the remains of her life; the silver-framed photograph of Richard, taken just before he sailed for France, the hairbrushes she had had as a wedding-present, the black silk cloak—part of her uniform as a widow, laid out across the foot of her single bed.

A friend of hers, who had lost her son at Arras, had tried hard to persuade her to go to a woman she knew of in Maida Vale. Not stances, just you and she together, and the room wasn't even darkened. This woman had worked in a shop. She was

quite uneducated. Her control was a Red Indian. Lily's friend said how weird it was to hear her, when she was in a trance, bellowing in a deep man's voice and shouting with laughter. She was very small and fragile. It seemed that the Red Indian had told Lily's friend that her son was happy and waiting for her to come to him. The poor mother had been so much cheered. It was pathetic. But Lily couldn't believe. No, not in the Red Indian, at any rate. It seemed that there were some things we weren't meant to know. One reads books like the Gospel of the Hereafter and everything seems so certain and beautiful and comforting. And then you try to go one step further, and there is only mockery and blackness.

Yet the temptation was very strong and it was always present. Suppose one went to that woman and did get a message—-just a few words, anything, so long as you could believe it was real. Suppose some woman held your hands and began speaking to you in your husband's voice. In Richard's voice. It would be ghastly, wonderful. One might walk out of that room and never feel unhappy again. Or perhaps, Lily thought, I should go straight home and drink something to send me to sleep. Then we could be together again at once.

Some time ago another friend had impressed Lily very deeply by describing how she had seen her dead husband standing, quite plainly, at the top of the staircase in her own house. Lily's friend

had had no doubt whatever that it was really he, that he had come to console her, to show her that he was still alive in another world.

Lily thought a great deal about this. Finally, she knelt down and prayed that Richard might appear to her. She made this prayer for several nights. During the earlier part of the War, when Richard was still alive, she had prayed regularly for his safety. Nearly everybody prayed then. But since his death she had said a prayer only occasionally, or in church. Several days passed. And then one evening, as she was coming up the staircase from the hall to dress for dinner, she saw Richard standing in front of her. It was getting rather dark, and he appeared, strangely distinct, within the archway of the corridor. He was as she had last seen him, on his last leave, a slightly bowed figure in the British Warm and frayed tunic, his mild eyes wrinkled like his father's, but prematurely, with his deeply lined forehead and large fair moustache. There he was. Then he was gone. Lily, who had paused for a moment on the top step of the staircase, walked dully past the place where she had seen him, and along the corridor, down to her room. For days she couldn't think clearly about what had happened. She attempted different moods, tried to feel that this was a sign, that at last she was calm, she was happy. But she wasn't. Doubts wearied her. She couldn't believe. She felt that what she had seen was a creation of her

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.