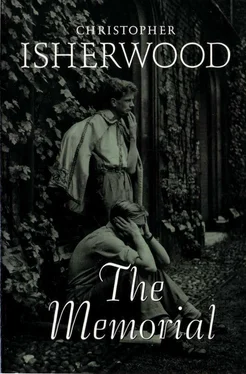

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I'll come on Monday," she said briskly, and kissed Lily, a thing she seldom did, as she got into the carriage. She could see that the public kiss

melted Lily at once. They both looked round for Eric, for Kent was ready on the box. He was dawdling just inside the gate, talking to Anne, and Mary moved towards them, calling: "Come along, children." Anne was in no hurry, but Eric started and flushed when he saw that he was keeping the carriage waiting. He blundered forward, nearly colliding with his aunt. He paused for an instant to try to apologise, and Mary had the impulse to say:

"If you like to blow in this afternoon, we shall all be at home."

He looked at her with his large, rather startled brown eyes:

"Oh, t-thanks awfully, Aunt Mm—"

"If you've got nothing more amusing to do," she added hastily, smiling, to cut short that awful stammer. And she signalled to Ram's B, who was talking to Edward Blake, that they were ready to start.

III

Ramsbotham was telling the not very new story of how, one week-end, the railway company had refused the responsibility of storing a consignment of his jute. So on Saturday evening he and Gerald and Tommy and a couple of watchmen had taken a lorry down to the station and brought the jute back, unloading it outside the mill gates and stacking it right across the roadway, so as to hold up the traffic. He'd been summoned, of course. Edward nodded, not listening to a word.

"I suppose everything'll go on much the same." Richard had said that, the last time Edward had seen him alive. He was sitting on the edge of an overturned wheelbarrow, a derelict, minus its wheel. He puffed his pipe. It was a blue, mild day. High above Armentieres an aeroplane caught the sun on its turning wing. There were heavy grumblings of artillery from the north. Behind them, some men were playing football near the farm with

the hole in the roof—Richard's billet. They sat at the edge of the muddy road, watching an enormous procession of lorries slowly bumping forward over the pot-holes.

They had been talking of that unimaginable time, the end of the War. Unimaginable, at least, for Edward. He'd never for a moment, he now felt, expected to come through, to see it. And there was Richard sitting on the wheelbarrow, puffing his pipe, speaking with such calm certainty, as though he meant to live for ever. It had done Edward good. He came away from this last meeting, as from their first, reassured and soothed.

Their last meeting wasn't, after all, unlike their first. Then, also, the future had seemed obscure and uncertain. Then, also, had Edward been oppressed by a fatalistic sense of helplessness, of being a tiny part of a machine. Not such a big machine. Only a school of four hundred boys. Yet now Edward remembered more clearly than this later afternoon in France that dreary Midland evening. How they'd all crowded together—the "new youths"—mutely wretched, wishing to efface themselves, unhappily trying to avoid the questions, the sarcasms of their seniors. And Edward Blake had trembled, loathing it passionately, more than any of the others, loathing and resenting it. Hating his parents for having sent him to such a place. He'd run away, he told himself, at once. He'd drown himself. Starve himself to death.

He'd never submit, not if they tortured him. He almost hoped they'd try.

From the very first, he'd been defensively on the lookout for marks of injustice and tyranny. He hadn't long to wait. His fag-master gave him three strokes because the sausages weren't properly cooked. How could you be expected to cook sausages if you'd never learnt and if the study fire had to be fed with coal-dust? How could you be expected, after a single week, to remember all the idiotic nicknames of the various masters? And fancy having to clean boots. What an indignity. You might as well be a slave. How did people endure it? Why didn't they rebel?

Why didn't they rebel? he'd asked Vernon; and Vernon had answered vaguely that he didn't know. He supposed that everyone had to put up with it, at first.

Already they were friends, and took, as a matter of course, their Sunday walks together. Over the moist fields to the wood where people smoked or along the banks of the wide muddy river as far as the chain-ferry. Richard Vernon was barely an inch the taller of the two, but Edward thought of him as being exceptionally large for his age. His mild, good-tempered air invested his broad shoulders with an added strength and solidity. The second and third termers, in exercising their prerogative of bullying the new youths, had preferred to leave Vernon alone.

Of Edward, who was wiry and strong as a monkey, they felt no such timidity. They attacked him continually, in the passages, in the changing-room, in the dormitory—and when, fighting with the power of desperation, he managed to keep three or even four of them at bay, they merely doubled their numbers and, getting him helpless at last, applied their clumsy traditional tortures, mocking his tears, which were not of pain but of rage.

Richard Vernon seemed mildly amused by the difficulties which Edward was perpetually creating for himself. He did not altogether believe that they were so necessary or so unavoidable. But his sympathy was entirely practical. He helped Edward with his sausages, his boot-cleaning and his impositions. As for his own work, he appeared to get through it without effort. From time to time he made mistakes, was punished, justly or unjustly, like all the others. It did not worry him. He forgot a beating as soon as he could comfortably sit down again.

Edward was amazed by his equanimity. Impatient at and furious with it by turns. But he could never finally condemn it. He gave up trying to quarrel with Richard and surrendered to a deepening admiration.

Their friendship survived the passing of terms and the sharpening of the almost comic contrast between them. Edward was going to take life by storm. He admitted no final obstacle, no barriers. He could do anything. He would do everything. He was jealous of the whole world. All that he read, either of heroism or of success, he applied at once to himself. Could I do that? Of course. And, what's more, I will. At school, he appointed definite objects for his ambition. He'd get into the cricket eleven. He had. He'd get into the football team. He hadn't, but that was, partly at any rate, because he'd sprained his ankle. He'd get into the Upper Sixth. He'd only reached the Lower—having decided on the way that work was a waste of time and that all the masters were incompetent fools. Everywhere he saw a challenge. His schoolfellows delighted in baiting him, encouraging him to break bounds, to go to the Green Man for beer, to let loose a guinea-pig in form, to put a chamber-pot on the arch of the school bell. How well they had understood him. He dared not refuse. He dared refuse no adventure—horribly frightened as he often was. He would have fought any boy in the school, would have got himself expelled for any offence, rather than admit to being afraid.

He was never popular. His violent, ill-balanced temper kept people at a distance. His jokes, overstrained and malicious, seldom raised a laugh. He was accused of playing games selfishly. When he worked hard in form he was called a sweatpot; when he slacked, the masters wrote scathing reports. The little group of Sixth Form intellectuals might have welcomed him, but he openly spurned them. The rest of the House found him over-subtle. He had started his school career by hating the school; he ended by despising it. And throughout he had no close friend but Richard.

Everybody liked Vernon. As he grew older he was universally known as Uncle Dick. He played cricket adequately, was a useful full-back for the House, did a sufficient amount of work to satisfy, if not to please, his form master. His laziness, of which he now made no secret, was a perpetual joke. Unnecessary exertion he frankly avoided. While Edward never missed an afternoon's exercise when games were not compulsory he played fives or went for runs—Richard preferred his study fire. The Spartan element in the House was inclined to be shocked, but, somehow, Vernon was never severely criticised. He had his own special position and it was respected.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.