Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

in a tin basin—on huge tips, grocer's bills, losses through holes in his pockets, he almost incredibly managed to spend about two thousand a year. Thank goodness, thought Mary, I've got that money out of him for Maurice's school, whatever happens.

It was really hard on Father that he didn't see more of Maurice—his favourite grandchild. But it was so unpleasant bringing the children to the Hall. Not that Lily would make the faintest fuss, of course. Sometimes Father came over to lunch in Gatesley, and then Maurice entertained him the whole time, showing him card tricks, explaining how the dining-room clock worked, asking: "Grandad, what would you do if you were alone in a forest at night, and you had no matches, and no food?" balancing a cricket bat on his chin. But Father was getting too shaky for that now. She'd sent the children over to see him by themselves, but they hadn't enjoyed it much. They liked being on their own ground, especially Maurice. She didn't blame him. She'd got into the habit of seldom blaming Maurice, and this, no doubt, was bad. Maurice was altogether too charming. Again and again she saw Desmond, in the way he smiled, cut the bread, ran upstairs, described a conversation. It was like the explanation of a trick. She could watch her son and say, yes—it was that which attracted me to his father, and that and that. She could only be taken in once in a lifetime, but

she could appreciate nature's cleverness. She could appreciate Maurice. This morning, for instance, she simply couldn't insist on his coming with them. And she might have known that Lily would notice—and remark on it. Well, let her notice. What had this service got to do with Maurice anyhow? No more than with Anne. But Anne took after her mother. She'll make some man a good wife, thought Mary, with resentment against men. I'll try to see that he isn't a Desmond, at any rate.

"I want to suggest to you," said the Bishop, "that this Cross stands for Freedom and for Remembrance. It stands also for Inspiration. I hope that, in days to come, the boys and girls who pass by this place will be told something of the heroism and self-sacrifice which it commemorates, and of the men who gave their lives in the service of that sacrifice."

There was one thing she would probably never tell either of the children. Desmond had spent his last leave in London. He had written to know if he might see her. They hadn't met for years. He didn't come to the house. He'd arranged a rendezvous by Cleopatra's Needle. He was forgetting his way about London now, he said. He'd been abroad most of the time. He wasn't changed in the least. They had tea at a Lyons' and walked up and down rather absurdly, like people waiting for a train.

He swore she was the only one he'd ever cared for. Where are the others now? thought Mary. And when this War is over, can we start again? Will you take me back? Yes, he asked that. She felt so much older than he was, old enough to be his mother. His mother, who'd written several times from Cork, very bitterly. She believed that Mary was the seducer, the betrayer of her son. He'd broken her heart. "No, darling," Mary told him—she shook her head, smiling, "I'd never have you back. Not if you paid me." She loved him better than ever at that moment, but differently. Love made her cunning. She would keep what she'd got—no more gambling. He was astonished, deeply injured innocent. He wasn't used to being treated like that by women. They parted quite good friends. And he was killed almost at once. She cried all day, but she wouldn't put on black. She wondered if the others had seen the name on the lists. It was never referred to. But perhaps Lily had gone through long indecisions wondering whether it would be proper for her to write and condole. Mary grinned. Lily was up at the Hall by then. She'd gone to live there almost as soon as the War broke out.

"There is one name, of all the names written here"—the Bishop made a backward, slight, somehow deprecatory gesture—"which I might specially recall to you. It is the name of a boy. Perhaps some of you here will, in a few years, be telling

your sons: That boy was your own age when he died fighting that you might grow up in a safe happy home. Yes, that boy was not yet sixteen when he was killed at Ypres. I hope that his name will never be forgotten in this village."

Mary didn't know it, but thought vaguely that he must be one of the Pratts from School Green. She seemed to remember having heard at the time. Meanwhile she felt someone pushing through the crowd just behind her. It was Ramsbotham— Ram's B, as the children called him—carrying the wreath. He took his station just behind Lily. He was crimson in the face.

It was all extraordinarily comic. But Mary could hardly believe that Lily had ever given him the slightest encouragement. He'd been at the Flower Show and the Sunday School Sports— where she hadn't, after all, turned up—and at the sale of work. It was getting talked about. Higham had remarked to Mary only the other morning: "Mr. Ramsbotham takes a lot of interest in Chapel Bridge affairs."

And of course he went over to the Hall as often as he got a chance, which was about once a month at best, poor man. Why, she wouldn't wonder if he hadn't originally encouraged Gerald and Tommy to come over so often to Gatesley because he wrongly imagined that it was an easy step from that to being invited to the Hall itself. Poor old Ram's B.

And what did Lily think about it all? Did she

know? Surely. But Lily might be capable of knowing or not knowing anything. And if she were told she would probably be very incredulous, and then a little shocked, and then faintly, rather unkindly interested—as though she'd heard about some curious new disease. Yes, a woman of Lily's sort could be exceedingly cruel.

They all started to sing the first verse of "Abide with Me." Mary began to feel stiff, and realised that she was very bored with this service. Why couldn't they have had something much shorter? She wondered what the account of it would sound like in the local paper. She was quite sure that the hymns would have been "very sympathetically rendered." Would there be a list of the principal "floral tributes"? Poor Ram's B must be hating theirs. It was horribly awkward to carry, to avoid crushing the lilies or letting the moss moult or getting pricked by the wire. She daren't look at his face again.

And really, thought Mary, I suppose it's hateful even to think of laughing here, at this service, for a hundred and three quite decent little men who all got killed stopping Germans flying the two-headed eagle on the Conservative Club. Yes, I do feel that. No, I don't, she revolted. After all, that's only snobbery. All this cult of dead people is only snobbery. I'm afraid I believe that. So much so, that the attitude which we're all subscribing to at this moment seems to me not only false but, yes,

actually wicked. Living people are better than dead ones. And we've got to get on with life.

The truth is, thought Mary, I want my lunch. And my corns ache dreadfully. And I despise men. Almost from the first, she knew, there'd been other women. Desmond scarcely concealed it after being detected once or twice. As he'd said, he had friends in London. Had she minded? She could scarcely remember. Yes, very much at the beginning. But soon she was used to it. She began to realise that she wasn't the only one who'd been treated in the same way. And there were the children. And the Chelsea people, whom she'd disliked and mistrusted so much at first, and who turned out to be quite decent and very kind. And there was her little house which she'd loved so dearly.

She'd often been sorry for Desmond, too. London didn't suit him. As an Irishman, he felt himself a kind of foreigner there. They'd talked of going to live in Paris, but nothing came of it. Ireland was out of the question. He could get no work, and there were his relations. His concerts, when he'd saved up for them—teaching, playing in theatre orchestras, and even once, as he'd foretold, in a restaurant, wearing a false moustache— weren't much of a success. The critics, he said, had made up their minds to ruin him. He shed tears. She comforted him. He was grateful, but soon went out; to be comforted more efficiently by somebody else.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

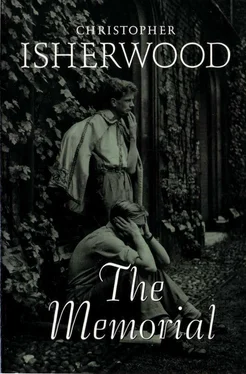

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.