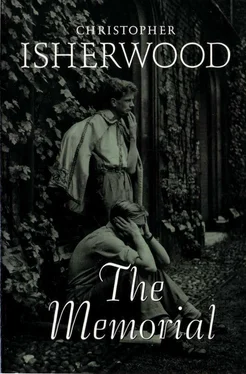

Balefanio - tmp0

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Balefanio - tmp0» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:tmp0

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

tmp0: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «tmp0»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

tmp0 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «tmp0», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Edward had visited Richard, too. Even after that scene he couldn't stay away altogether. And both Richard and Lily had sent him notes—Lily's bright and semi-formal; Richard's cordial but brief. "You must try and find the time to look us up soon." That was irony indeed. Time—Edward had nothing but Time. He fidgeted about Town, dabbled and dawdled, could settle to nothing. From a seat in the park, from an armchair in his club, he regarded the enormous horizons which opened before his time, his money and his talents. Such horizons appalled him. He ordered a drink. Then another.

And at Earl's Court Lily welcomed him with conscientious brightness. She didn't like him, he knew that. Well, he didn't like her either. She left Richard and Edward alone together, after dinner, with some ceremony. "I know you've always such a lot to talk about." They had absolutely nothing. Richard, who wouldn't admit this, it seemed, even to himself, filled the silence between them with loud, uneasy joviality. When they were all three upstairs, later, in the drawing-room, the eyes of the married pair scarcely left each other for a moment. They appeared almost to forget his presence. Edward generally made an excuse to be out of the house before ten. At this they were genuinely surprised. Richard, indeed, had actually expressed his qualms:

"I'm afraid you find it pretty slow, spending

the evening here?" he had asked, with an anxiety which would have been rather pathetic were it not so irritating, as he stood in the hall, ready to show Edward out.

To escape from those two houses, he had travelled. China. South Africa. Brazil. Twice round the world. Had shot big game, climbed in the Alps, been round the coasts of Europe in a small sailing-boat. At any rate, he could afford to risk his life expensively. And he was happier away from England.

And then the War. And that last afternoon with Richard, sitting talking by the side of a muddy road. Edward was glad to be able to remember that afternoon. He'd taken a good deal of trouble to procure it, wangling things at the aerodrome, getting a fifty-kilometre lift, bribing the telephonist to put through a private message to Richard's mess. He hadn't expected anything but a sentimental pleasure from the meeting. And, after all, it had been a success. For Richard, away from Earl's Court and his office, had seemed again the Richard of their schooldays. He was busy knitting. He offered Edward a pair of mittens. And Edward had been wearing them when he crashed. They must have been cut off him at the hospital with his other clothes and thrown away or burnt. It was a pity, because he had nothing, absolutely nothing to remind him of Richard as he used to be, as he was when he died.

Ramsbotham had finished his story about the jute and was beginning another, also not new, about an accident with the transformer. Mary beckoned to them to make haste. Two men, said Ramsbotham, had been killed. Richard had been killed. Richard, who had said that everything would go on much the same. Richard is dead. And this is what remains, said Edward to himself, seeing the doll in her black, the slobbering old man, the gawky boy getting into the carriage. This is what we've got left of Richard.

IV

Eric jumped into the victoria, nearly treading on his mother's foot. Squatting down on the back seat, with his knees sticking out, he felt clumsy and huge—all bones.

His clumsiness was loathsome to him. He put his hands round his knees to make himself more compact in the narrow space. But his hands were as bony as his knee-joints, and always either too hot or too cold.

He looked at his mother, to see that he had not offended her. But Lily's eyes were fixed on the tree-tops, dreamily watching the rooks. He looked at his grandfather, and John smiled at him, widely, out of his bland, collapsed face. They were moving away from the church. The heavy line of Cobden rose above the trees. The white farms were sprinkled on its back like grains of salt. Eric began to think about the boy who had been killed in the War.

"I've asked Mary to come and lunch next Monday," said Lily to John. "Will that be all right?"

John smiled at her. Then he nodded, with a little grunt.

Eric had never heard of the boy before. He felt that he would like to find out about him, and wondered whom he should ask. Kent would probably know. Kent knew almost everybody in Chapel Bridge. When they were out driving people often touched their hats or nodded: Good morning, Mr. Kent, who never took any notice of Grandad at all. Mother said that this was simply deliberate Socialistic rudeness. But it couldn't be stopped. It wasn't Kent's fault.

That last spring of the War, in the Easter holidays, Maurice had said laughingly one day: "Suppose we join up, Eric?"

They had been alone together at the time, and though Maurice had laughed, he'd meant what he said, so Eric thought. Maurice had a way of half-jokingly suggesting doing a thing and then, if anyone agreed or dared him to do it, doing it at once—with so much decision that you felt he'd been meaning to, all the time. Only last spring, they'd been up in his bedroom one day and Gerald Ramsbotham had started talking about heights. Gerald said the bedroom was thirty feet from the ground. Maurice said: "No, not nearly that." Gerald said: "Anyhow, I bet you wouldn't like to jump out." "Do you," said Maurice, smiling. "How much?" Gerald said sixpence and Tommy said ninepence. Maurice had climbed out on to

the sill and jumped. He landed in a flower-bed, the only one in the garden, and lay there shouting to them to chuck him down the money. His ankle was twisted a bit, but nothing serious.

Those words of Maurice's had thrown Eric into a fever of doubts and hesitations for the rest of the holidays. Almost every day he was on the point of going to Maurice and saying: "Come along. I'm ready." Every night he lay awake for hours thinking about it, screwing himself up. At night, in the darkness, he was brave. The adventure seemed possible, almost easy. He saw it before him in the blackness, lived through it in all its stages. They would have been passed, almost certainly. They were tall for their age at fifteen, and at that time, with the German Push going forward, they couldn't afford to be particular whom they took. Eric saw their life together in the training-camp, watched himself and Maurice drilling, being taught how to fight with bayonets, embarking on the troopship, cheering from French trains—Are we downhearted?—arriving in billets, going up along miles of communication trenches to the front line, waiting for the zero hour at dawn, in thin rain. He weighed, tasted every experience, every hardship —decided that, with Maurice, he could face them all.

It hadn't been a mere day-dream, either. Again and again he'd all but asked the question. And of course Maurice would have come. The truth

was, he'd been held back by pure fear—nothing else. Yes, I'm a coward all right, Eric thought.

But suppose he had known then of someone else—of his own age—who'd done the same thing. This boy, for instance. That example might just have turned the balance. And so, one night, they'd have run away, caught an early morning train into Manchester, leaving notes in their bedrooms. And, as a matter of fact, the War would have been practically over before they got out to the Front at all. And now they'd be war heroes, old soldiers, as good as grown-up men, respected by everybody. Or their names might be written with his father's on the Cross. Eric preferred to think of that. No, not Maurice's name. His own, only. He had saved Maurice's life. They got him back to the base hospital, fatally wounded. He felt no pain. Maurice came and knelt by his bed. Oh, Eric, why did you do it? I don't deserve it. But Eric smiled and said: I'm glad I did it, Maurice. You mustn't cry like that. You must try to make things easier for my mother. Maurice was standing today beside Aunt Mary and Anne at the Cross. Maurice wore a black band round his arm. They talked of Eric. Maurice said: We shall never forget him. Never. What bloody trash, cried Eric to himself, pouncing suddenly upon the day-dream, kicking it savagely, smashing it to atoms.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «tmp0»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «tmp0» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «tmp0» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.