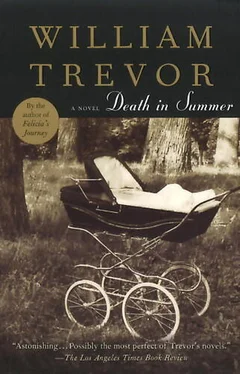

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You don’t go messing with the Dowlers, Albert. You leave them be.’

‘I only wanted to put it to them.’

‘You leave them be. Cheers, Albert.’

‘Take care now, out there on your own.’

‘Yeah, sure.’

As she always does, Pettie buys the cheapest ticket at the Tube station in order to get past the barrier. Two youths on the train keep glancing in her direction. They’re the kind who don’t pull their legs back when you stand up, obliging you to walk around them: Pettie has experienced that on this line before. Ogling her, one of them holds his hands out, palms facing each other, indicating a length, as a man boasting of a caught fish might. But Pettie knows this has nothing to do with fish. The other youth sniggers.

She looks away. The uncle with the birthmark took off her glasses the first time they were on their own. ‘Let’s have a look at you,’ he said and put the glasses on the windowsill. ’Oh, who’s a beauty now?’ he said, and when he whispered that he liked her best a warmth spread through her that came back, again and again, whenever he said it.

The youths get off at Bethnal Green. One of them says something but she doesn’t hear it, not wanting to. ‘Prim little lady,’ the uncle who liked her said. ‘Who’s my prim little princess?’ He told her what a cheroot was because he had a packet in his pocket. She was prim and she still is; being prim is what she wants. ’Never so much as a morsel taken from the knife,’ Miss Rapp read out from the Politely Yours column. ’Return the fork to the plate between mouthfuls.’ She practised that, and Miss Rapp was pleased.

Aldgate goes by, and Bank; Pettie closes her eyes. Wild summer flowers are in bloom, and it could be the picture on the floor but it isn’t because she’s in the picture herself. She’s in the lane with a buggy, far beyond the few houses by the shop and the petrol pump, far beyond the church and the graveyard and the gateless pillars of the house. She’s walking out into the countryside, and fields stretch to the horizon, with the wild flowers in the hedges, a plain brick farmhouse in the distance. ‘Look, a rabbit,’ she whispers, and Georgina Belle waves at the rabbit from the buggy, and you can smell honey in the honeysuckle.

At Oxford Circus she goes with the crowd, jostled on the pavement. A gang of girls gnaw chicken bones and drink from cans, laughing and shouting at one another, strung out, in everyone’s way. Beggars poke out their hands from doorways, tourists dawdle, litter is thrown down. Street vendors sell perfume and watches and mechanical toys. Men in coloured shorts unwrap summer lollipops. Women expose reddened thighs. ‘Thaddeus Davenant,’ Pettie says aloud.

He ran his fingers along the pale wood that edged the back of the sofa, standing there for a moment before she sat down, the grandmother already occupying a chair. He was solemn, not smiling when she held out the reference and the certificate. Still mourning his loss, he naturally wouldn’t have smiles to spare. Something about him reminds her of the man who talked to her in Ikon Floor Coverings, who explained why he recommended 0.35 wearing thickness in a vinyl. Thaddeus Davenant’s clothes were nothing like the grey suit and clean white shirt, Eric on the badge in the lapel, but there was something about his quiet manner that reminded her. More than once she went back to Ikon Floor Coverings, until the time he wasn’t there, gone on to another store, they didn’t know where. Not that she wants to think about the floor-coverings man now, nor the Sunday uncle either, since they let her down in the end. ‘Oh, yes, a lovely walk.’ Pettie says instead, and Thaddeus Davenant takes his tiny daughter from her arms. ‘Georgina Belle,’ he says.

Carefully, Albert attaches the Spookee sticker to his wall. He has all eight of the Spookee stickers now, collected from Mrs. Biddle’s cornflakes’ packets. He stands back a foot or two to inspect the arrangement, his empty eyes engaged in turn with each of the grey, watery creatures, one with a red tongue lolling out, another gnashing devilish teeth. He moves further away, surveying the stickers from the door in order to see what the decoration looks like just in case Mrs. Biddle ever glances in, not that she can manage the stairs, but you never know.

Albert looks after Mrs. Biddle in return for this room. Years ago, when he and Pettie ran away from the Morning Star, they slept rough, at first in an abandoned seed nursery and after that in cars if they could get into them, or in sheds left unlocked on the allotments that stretched for half a mile behind a depository for wrecked buses. In time Albert heard about the night work on the Underground; he slept by day, on benches or in waiting-rooms. Then, because he happened to be passing, he helped a man with elephantiasis to cross a street and the following morning he noticed the man again and helped him again, this time carrying for him a pair of trousers he was taking to a dry cleaner’s.

Albert waited on the pavement outside the cleaner’s and when the man emerged he fell into step with him. He felt compassion for the man’s suffering — the great bloated body, the moisture of sweat on his forehead and his cheeks, the difficulty he experienced in gripping with his fingers. Albert did not say this but simply walked beside the man, restraining his own natural motion so that it matched the slow drag of the man’s. They did not speak much because speech was difficult for the man while he was engaged in the effort of movement, but when they reached a small supermarket — the Late-and-Early KP Minimarket — he thanked Albert for his assistance and his company, and turned to enter the place. He had time to spare, Albert said, and followed him in.

He carried the wire basket around the shelves, filling it as he was directed. The man rested, leaning against the shelves where tins of soup and vegetables were stacked, calling out to Albert the remaining items on his list. A family of Indians ran the minimarket, two young men and their parents, the mother at the till. When the shopping was complete and paid for, Albert took the carrier-bags that contained it and the man did not demur, although when they were on the street again he might have been left standing there. Later, when he and Albert knew one another better, the man mentioned that. It would not have been an unusual occurrence nowadays for a young person to befriend an afflicted man in order to steal from him when the moment was ripe. ‘But though I look no more than sawdust in a skin,’ the man with elephantiasis stated, ‘I can spot an honest face.’

On the morning of the shopping expedition he had led the way to his council accommodation and had invited Albert in when they reached it. He was tired, resting again while Albert, at his instruction, buttered cream crackers and prepared two cups of Bovril. He noticed that the man was not in the habit of washing the dishes he ate from and so, every morning after this one, Albert called in to attend to the chore, to make the Bovril and at one o’clock to open a tin of beans, which they shared on toast, with a banana afterwards. Still unable to afford a place to sleep, his work on the Underground being ill-paid, Albert was grateful for the comfort of the man’s rooms, for the armchair that became the one he always sat in, for the warmth and the food. But this convenience was not his motive. He did not seek to cultivate a relationship for profit: it had come naturally to him to assist the man across the street when he recognized signs of stress. It was natural, too, that he should have accompanied him to the Late-and-Early KP Minimarket and should have carried his purchases. Not much thought, certainly no cunning, inspired these actions. Elephantiasis Albert wrote down, having asked the man how he was spelling that. He liked the sound of the word; he liked the look of the letters when he wrote them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.