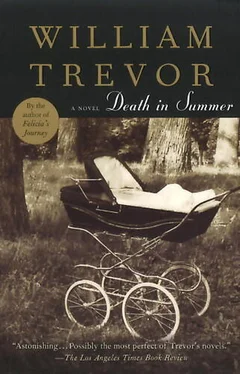

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘They didn’t have no tambourines the day I asked the man, Mrs. Biddle. In their lunch hour it was.’

‘Same difference to me, Albert. All that about a burning bush, all that about a star. They lull you with the music.’

Albert doesn’t protest further. He collects a cup and saucer he hasn’t noticed on the window-ledge. Mrs. Biddle says there’s trouble with the Lottery.

‘Some man strung himself up. Win the Lottery and it’s the end of you, the new thing is.’

Albert asks about that, picking up the tray. It could be you have to pay for the uniform. Stands to reason, the Army couldn’t go handing out clothes. Albert understands that, but doesn’t say so now because her attention wanders whenever he mentions the Army — the way it does when he says SAS or Air India has just gone over, or when he tries to tell her about Joey Ells. The time he told her about scratching his initials on the brick under the windowsill at the Morning Star she fell asleep.

‘A couple of thousand you’d get in the Irish Sweep. Enough for anyone.’

‘Course it is, Mrs. Biddle.’

Twice he put his initials there, A. L., and the year, 1983. It was Mrs. Hoates who told him his other name was Luffe, something he hadn’t known. She’d chosen Luffe because it suited him, she said. Albert Luffe. She spelt it for him when he asked and he wrote it down.

‘Get us a curry later on, Albert? Something from Ishi Baba’s?’

Albert holds the tray with one hand while he opens the door. No problem about a curry. He’ll have a sleep and then he’ll see what’s on offer.

‘You know what I’d like, Albert?’

‘What’s that then?’

‘You make me a jelly, Albert? You make me a jelly and put it in the ice compartment for tonight?’

He nods, and Mrs. Biddle declares that with a jelly to look forward to she’ll get up. She’ll get up and she’ll catch the afternoon sun by the window. Then there’ll maybe be something on the TV. A load of rubbish, that show with the boxes was, the man’s clothes too tight on him.

‘Good for you to get up.’ Albert repeats what a woman in the KP told him when he reported that sometimes he has difficulty persuading Mrs. Biddle to leave her bed. Bedsores there could be, apparently. Joints seizing up if you lay there.

‘You got a red jelly at all, Albert?’

‘Yeah, I got one.’

The Morning Star has come into his mind because of remembering the initials. Miss Rapp in the mornings with ‘O Kind Creator’, her fingers dashing along the piano keys. Mrs. Cavey on her hands and knees in the bootroom, red polish on a hairbrush. Plaster falls from the stairway wall, the smell of boiling cabbage creeps upstairs. The cars come on a Sunday, the coats hang on the hallstand, big heavy coats worn to Rotary and to church, dark hats on the curved pegs, the uncles’ gloves on the shelf below the mirror. Johneen Bale was given a dress and socks an uncle’s children had grown out of, Leeroy a bottle-opener, the mongol girl a bangle she sold to Ange, Ahzar and Little Mister frisbees. Cakes and jamrolls there were, beads and rings and plastic puzzles: he found the places to hide when they didn’t want to take the presents any more. ‘Don’t bother me now, boy,’ Mr. Hoates said every time he tried to tell, Mr. Hoates gone sleepy, his hour of Sunday rest, his gas fire hissing. Mrs. Cavey said wash your mouth out. ‘Stay by me, Albert,’Joey Ells begged, but he couldn’t that time and she hid in the rainwater tank, crawling under the strands of barbed wire, making a gap in the planks that covered the manhole. ‘Who’s seen Joey Ells?’ Mr. Hoates asked at Sunday tea and someone said there was snow on the ground, there’d be her footprints. ’Shine your torch down, Albert,’ Mr. Hoates said, and she was there with her legs broken. Mrs. Hoates went visiting on a Sunday afternoon, when the uncles came. ‘Now, what d’you want to do that for?’ she said to Joey Ells when she returned. ‘Frightening the life out of us.’

In the kitchen Albert washes up. The Chicken Madras is always the preference from Ishi Baba’s. He doesn’t mind himself, the Chicken Madras or the beef, whatever’s on. He separates the squares of a Chivers’ strawberry jelly and when the water on the gas jet boils he pours it on to them, stirring until they dissolve.

No way will Pettie have money for the rent if she doesn’t go back to the Dowlers or start in somewhere else. Come Friday there’ll be the knocking on the ceiling with the walking-stick and Mrs. Biddle saying she’s not a charity. She never wanted that girl in the house in the first place, she’ll remind him, which from time to time she does anyway, rent or no rent. It rouses her suspicion that Pettie keeps a low profile in the house, hardly making a sound on the stairs or when she opens the front door or closes it behind her. Claiming that the sitting-room has a smell, she never looks in for a chat with Mrs. Biddle. It worries Albert that she won’t be able to find other employment and will make for the streets where Marti Spinks and Ange hang about, where Little Mister’s with the rent boys. ‘Don’t ever go up Wharfdale,’ he has warned her often enough, but sometimes she doesn’t answer.

Finding room for the jelly among packets of frozen peas and potato chips in the refrigerator, Albert’s concern for Pettie gathers vigour. She won’t be able to give him back the money she borrowed, and when he asks her what she’s doing for work she won’t say. She’ll sit there in the Soft Rock, making butterflies out of the see-through wrap of a cigarette packet or tapping her fingers if the music is on, not hearing what’s said to her because of this house she has been to. He’ll say again that he should go round to the Dowlers to try to get the job back. The chances are she won’t answer.

A fluffy grey cat crawls along the windowsill, pausing to look in at him. Albert doesn’t like that cat. Closing the refrigerator door, and catching sight of the animal again as he turns around, he remembers how it once jumped down from the opening at the top of Mrs. Biddle’s window and landed on her pillow, terrifying her because she was asleep. The cat is another worry Albert has, though nothing like as nagging a one as his worry about Pettie. As if it knows this and is resentful, it mews at Albert through the glass, displaying its pointed teeth. There’s a cat that goes for postmen’s fingers when they push the letters into the box, vicious as a tiger, a postman told him.

The mewing ceases and Albert is spat at. Claws slither on the window-pane, the fluffy grey tail thrashes the air, and then the creature’s gone. It’ll be the end of her if Pettie goes up Wharfdale, same’s it was for Bev.

At a scarf counter she unfolds scarves she can’t afford to buy, trying some of them on. Busy with another customer, the sales assistant isn’t young, a grey, bent woman whom Pettie feels sorry for: awful to be on your feet like that all day long, at the beck and call of anyone who cares to summon you, forever folding the garments that have been mussed up.

In the coat department the assistant is younger, a black girl with a smile. She keeps repeating that the blue with the ows at the collar suits Pettie, and brings her a yellow and a green of the same cut. ‘Course the bows slip on and off, you have what colour bow you want,’ the black girl points out, and Pettie is reminded of Sharon Lite, who had to have electric-shock treatment years afterwards. Albert occasionally comes across someone from the home, someone who recognizes him on the street or in an Underground, who passes on bits of news like that. ‘No, sorry,’ Pettie apologizes, and the black girl says she’s welcome.

In a shoe shop she tries on shoes, fifteen pairs in all. She walks about with a different shoe on either foot. She asks for half a size larger and begins again. She asks about sandals, but sandals are scarce at the moment, she’s told, everyone after them. She examines the tights on a rack by the doors and leaves the shop with a pair of navy blue and a pair of taupe. No way you can walk out of a store with a coat, but at least she has a scarf with horses’ heads on it, and a blue bow and a silvery one, and the tights.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.