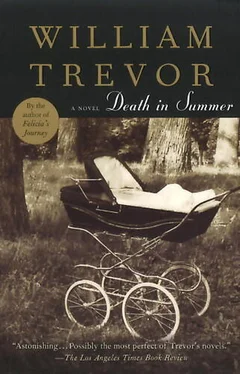

William Trevor - Death in Summer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Death in Summer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death in Summer

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death in Summer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death in Summer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death in Summer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death in Summer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Quiet,’ Pettie says. ‘I never knew a place as quiet.’

It was quiet when she walked up to the front door and in the hall, in the room where the interview was and on the stairs, on the landing even though those two people were there. Albert listens while more details of the nursery are given, but in his mind’s eye he sees the playroom at the Morning Star, where there were toys also — train trucks with a wheel gone, limbless dolls, jigsaws with half the pieces missing, anything that other children had finished with. Old armchair cushions were drawn close to the stove that smelt of burning paraffin in winter. Doorless lockers filled one wall. It was here that Marji Laye told how her father and mother were ice-rink skating stars who had put her in a home for the time being, better than carting her about with them all over the world, depriving her of an education. Sylvie talked about parties, someone playing the melodeon, everyone happy until there was a fire and she was the only one left. Bev said her father was in the House of Lords and knew the Queen. But Joe Minching said Sylvie’s mother and sisters were on the game and always had been, that Marji Laye was found wandering on a tip, that Bev came in a plastic bag. From the playroom windows you could see Joe Minching’s coke shed, and the tall yard doors with the dustbins in a row beside them, straggles of barbed wire trailing round the manhole of the underground tank that used to conserve rainwater in the old days, its missing cover replaced by planks weighed down with concrete blocks.

‘Georgina Belle,’ Pettie says. ‘When I saw her I kept thinking I’d call her Georgina Belle. I’d get the job and I’d call her that. We’d go downstairs and the grandmother would have changed her mind on the way. The way he smiled when he was patting the dog, you could see he’s keen.’

‘Keen, Pettie?’

‘Keen I’d come there is all I mean.’

Albert doesn’t respond to that. There’s an aeroplane passing over and what he’d like to do is go to see what line it belongs to, to wait for it to come closer and catch the emblem. But this is not the morning for that, and instead he makes another effort at distraction.

‘You give that bugle in, Pettie?’

A week ago, when they had left the Soft Rock Café and were walking about, Pettie found a bugle in a supermarket trolley that someone had abandoned in a doorway. She tried to blow it but no sound came, and Albert wasn’t successful either. A special skill, a man going by said.

‘Yeah, I give it in.’

‘Salvation Army property.’

‘I give it in at the hostel.’

She took it to a man who buys stuff for car-boot sales, who generally accepts anything she brings him. He said at first the bugle was worthless. In the end he gave her forty pence for it.

‘Salvation Army do a good job, Pettie.’

The grandmother took her into the bed-sitting room they’d got ready for the minder. ‘Come next door, Nanny,’ she said. Why’d the woman bring her in there if they didn’t want her? Why’d she bother? Why’d she even bring her upstairs? Why’d she call her that? ‘Course she wouldn’t change her mind. All the time she was against her.

‘I asked at the hostel,’ Albert says. ‘I said I couldn’t play an instrument, but the man said no problem if I wanted to join the Army.’

The couple were moving away from the landing when they passed again, the man carrying the stepladder. ‘Wait here a minute, would you?’ the grandmother said in the hall. A clock in the panelling ticked and there were voices from behind the closed door, but she couldn’t hear what was being said. The voices went on and on, and then the old woman came out. She shook her head. Twice she said she was sorry.

‘Best forgotten, Pettie.’

‘She give me a ten-pound note for the fare. Ten pounds eighty it cost me.’

‘You like I go round and put it to the Dowlers for you?’ Another smile lights Albert’s eyes, upsetting the composure of his face, crinkling his cheeks and forehead. ‘You like I say you made a mistake about the job?’

‘The Dowlers are the pits.’

Eight till eight, the arrangement at the Dowlers’ was, but more often than not neither parent turned up till ten, with never a penny offered for the extra hours. ‘Give them something about six,’ Mrs. Dowler would say, and there was always a fuss because they didn’t like what was in the few tins that were regularly replaced on the kitchen shelves. Dowler fixes people’s drains for them, driving about in a van with Dowler Drains 3-Star Service on it, a coarse black moustache sprawled all over the lower part of his face. Overweight and pasty-skinned, Mrs. Dowler in her traffic-warden’s uniform harangues her children whenever she’s in their company, shouting at them to get on, shouting at them to be quiet, telling them to wash themselves, not noticing when they don’t. ‘They had the NSPCC man round,’ the woman next door told Pettie once, and Pettie realized then that she was only there because the NSPCC man had ordered Mrs. Dowler to get a daytime minder.

‘You lend me a few pounds, Albert?’

He counts the money out in small change. He makes stacks of the different coins on the table and watches Pettie scoop them into her purse. Two girls have come into the café and are playing the fruit machines. The lights of the antiquated juke-box have come on. The deaf and dumb man is still in the window, the middle-aged couple still don’t speak. The red-haired proprietor turns over a page of his newspaper.

‘Fancy the dinosaurs, Pettie?’

He smiles, but when she shakes her head the light goes from his eyes and his features close in disappointment. It was her idea to go to see the dinosaurs in the first place. A million years old, those bones, she said.

‘Fancy going out to the Morning Star?’

When they were still there the Morning Star home was condemned as unfit for communal habitation. The inspectors who came round investigated the load-bearing walls, took up floorboards and registered on their meters the extent of damp and rot. A year after Albert and Pettie left they went back to look. Site for Sale after Demolition, a notice said. They managed to get in, and still occasionally return to wander about the passages and rooms, Albert showing the way with his torch.

‘No, not the Morning Star.’ Pettie shakes her head again. ‘Not today.’

Albert drinks the last of his milky tea, cold now in the glass mug. She won’t be comforted. Sometimes it’s as though she doesn’t want to be. Her high-heeled shoes are scuffed, her white T-shirt has traces of reddish dye from some other garment on it. He knows from experience that she’s in the dumps.

‘What you going to do, Pettie?’

‘I got to sort myself. I got to go wandering.’

‘Down the shops, Pettie? I need a battery myself.’

‘I got to be on my own today.’

She stands up, telling him he should rest because of his night work. He needs to sleep, she reminds him, everyone needs sleep. Albert works in Underground stations, erasing graffiti when the trains aren’t running.

‘Yeah, sure,’ he says, because it’s what she wants. The girls playing the fruit machines move from one to the other, not saying anything, pressing in coins and hoping for more to come out, which sometimes happens.

‘Yeah, sure,’ Albert says again.

She knows he’s worried, about the job, about the rent, maybe even because she has feelings for that man. Not being the full ticket, he worries easily: about cyclists in the traffic, window-cleaners on a building, a policeman’s horse one time because it was foaming at the teeth. He worried when they found the bugle, he worried when Birdie Sparrow found a coin on the street outside the Morning Star, making her give it in because it could be valuable and she’d be accused. He said not to take them when the uncles came with their presents on a Sunday, but everyone did. He was the oldest, the tallest although he wasn’t tall. The first time he helped Marti Spinks to run off in the night they caught her when it was light, but she never said it was he who had shown her how. The next time she got away, with Merle and Bev. When Pettie’s own turn came he said he was coming too because she had no one to go with. ‘Best not on your own,’ he said, and there wasn’t a sound when he reached in the dark for the keys on the kitchen hook, nor when he turned them in the locks and eased the back door open. He didn’t flash his torch until they’d passed through the play yard and were half-way down the alley, the long way round to Spaxton Street but better for not being seen, he said. ‘Crazy’s a bunch of balloons,’ Joe Minching used to say, but nobody else said Albert was crazy, only that he wasn’t the same as the usual run of people.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death in Summer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death in Summer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death in Summer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.