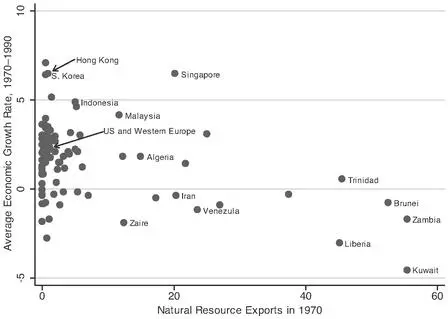

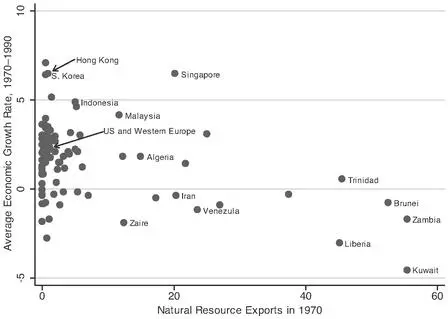

FIGURE 4.2 Growth and Natural Resource Abundance, 1970–1990

One interesting manifestation of the differences between wealth and poverty in resource-rich lands is the cost of living for expatriates living in these countries. While it is tempting to think that cities like Oslo, Tokyo, or London would top the list as the most expensive places, they don’t. Instead it is Luanda, the capital of the southwestern African state of Angola. It can cost upwards of $10,000 per month for housing in a reasonable neighborhood, and even then water and electricity are intermittent. What makes this so shocking is the surrounding poverty. According to the United Nations Development Program, 68 percent of Angola’s population lives below the poverty line, more than a quarter of children die before their fifth birthday, and male life expectancy is below forty-five years. The most recent year for which income inequality data are available is 2000. These data suggest that the poorest 20 percent of the population have only 2 percent of the wealth. Angola is ranked 143 out of 182 nations in terms of overall human development. Prices in Angola, as in many other West African states, are fueled by oil.

The resource curse enables autocrats to massively reward their supporters and accumulate enormous wealth. This drives prices to the stratospheric heights seen in Luanda, where wealthy expatriates and lucky coalition members can have foie gras flown in from France every day. Yet to make sure the people cannot coordinate, rebel, and take control of the state, leaders endeavor to keep those outside the coalition poor, ignorant, and unorganized. It is ironic that while oil revenues provide the resources to fix societal problems, it creates political incentives to make them far worse.

This effect is much less pernicious in democracies. The trouble is that once a state profits from mineral wealth, it is unlikely to democratize. The easiest way to incentivize the leader to liberalize policy is to force him to rely on tax revenue to generate funds. Once this happens, the incumbent can no longer suppress the population because the people won’t work if he does.

The upshot is that the resource curse can be lifted. If aid organizations want to help the peoples of oil-rich nations, then the logic of our survival-based argument suggests they would achieve more by spending their donations lobbying the governments in the developed world to increase the tax on petroleum than by providing assistance overseas. By raising the price of oil and gas, such taxes would reduce worldwide demand for oil. This in turn would reduce oil revenues and make leaders more reliant on taxation.

Effective taxation requires that the people are motivated to work, but people cannot produce as effectively if they are forbidden such freedoms as freedom to assemble with their fellow workers and free speech—with which to think about, among other things, how to make the workplace perform more effectively, and how to make government regulations less of a burden on the workers.

Borrowing

Borrowing is a wonderful thing for leaders. They get to spend the money to make their supporters happy today, and, if they are sensible, set some aside for themselves. Unless they are fortunate enough to survive in office for a really long time, repaying today’s loan will be another leader’s problem. Autocratic leaders borrow as much as they can, and democratic leaders are enthusiastic borrowers as well.

We are all at least a little bit impatient. It’s in our nature to buy things today when better financial acumen might suggest saving our money. Politics makes financial decision making even more suspect. To understand the logic and see why politicians are profligate borrowers, suppose everyone in a country earns $100 per year and is expected to do so in the future too. The more we spend today, the more we must pay in interest and debt repayment tomorrow. Suppose, for instance, that to spend an extra $100 today we have to give up $10 per year as interest payments in the future. It is reasonable to see that people could differ on whether this is a good idea or not, but politics certainly makes it more attractive. To simplify the issue vastly, suppose leaders simply divide the money they borrow among the members of their coalition. This encourages leaders to borrow more. If a leader has a coalition of half the people and he borrows an amount equivalent to $100 per person, then everyone has to give up $10 in each future year (as taxes to pay the interest). However, since the coalition is only half the population, each coalition member’s immediate benefit from the borrowing is $200. While to some this might still not seem like an attractive deal, it is certainly better than incurring the same debt obligation for $100. Governments of all flavors are more profligate spenders and borrowers than the citizens they rule. And that profligacy is greatly multiplied when we look at small coalition regimes.

As the size of the coalition shrinks, the benefits that the coalition gains from indebtedness go up. If, for instance, the coalition includes one person per hundred then, in exchange for the debt obligation, each coalition member receives $10,000 today instead of the mere $200 in the 50 percent coalition example. This is surely a deal that most of us would jump at. As the coalition size becomes smaller, the incentive to borrow increases.

Of course, borrowing more today means higher indebtedness and a smaller ability to borrow tomorrow. But such arguments are rarely persuasive to a leader. If he takes a financially reasonable position by refusing to incur debt, then he has less to spend on rewards. No such problem will arise for a challenger who offers to take on such debt in exchange for support from members of the current incumbent’s coalition. This makes the current leader vulnerable. Incurring debt today is attractive because, after all, the debt will be inherited by the next administration. That way, it also ties the hands of any future challenger.

A leader should borrow as much as the coalition will endorse and markets will provide. There is surely a challenger out there who will borrow this much and, in doing so, use the money to grab power away from the incumbent. So not borrowing jeopardizes a leader’s hold on power. Heavy borrowing is a feature of small coalition settings. It is not the result, as some economists argue, of ignorance of basic economics by third-world leaders.

In an autocracy, the small size of the coalition means that leaders are virtually always willing to take on more debt. The only effective limit on how much autocrats borrow is how much people are willing to lend them. Earlier we saw the paradoxical result that as Nigeria’s oil revenues grew so did its debt. It wasn’t that the oil itself encouraged borrowing—autocrats always want to borrow more. Rather revenues from oil meant that Nigeria could service a larger debt and so people were more willing to lend.

Although the large coalition size in a democracy places some restrictions on the level of borrowing, democratic leaders are still inclined to be financially irresponsible. Remember, while the debt is paid by all, the benefits disproportionately flow to coalition members. Over the last ten years the economies of many Western nations boomed. This would have been a perfect time to reduce debt. Yet in many cases this did not happen. In 1990, US debt was $2.41 trillion, which was equivalent to 42 percent of GDP. By 2000 this debt had grown in nominal terms to $3.41 trillion, although in relative terms this was a decline to 35.1 percent of GDP. However, as the economy prospered during the 2000s, debt continued to slowly accumulate instead of shrink. In 2007, before the financial crisis, US debt stood at $5.04 trillion or 36.9 percent of GDP. A bigger economy means a greater ability to service debt and a capacity to borrow more.

Читать дальше