To a certain extent, Reagan was right: lower taxes encouraged people to work and so the pie grew. However, crucially, in democracies it is the coalition’s willingness to bear taxes that is the true constraint on the tax level. Since taxes had not been so high as to squash entrepreneurial zeal in the first place, there wasn’t much appreciable change as a result of Reagan’s tax cuts. The pie grew a little, but not by so much that revenues went up.

Today, the Tea Party wing of the Republican Party seeks to reenact tax-cutting policies similar to Reagan’s. Like him, they argue that tax cuts will grow the economy. The lesson from the Tea Party movement’s electoral success in 2010 is that people don’t like paying taxes. Politician who raise or even maintain current taxes are politically vulnerable, but then so too are politicians who fail to deliver the policies their coalition wants. Herein lies the rub. It may well be that cutting taxes, while increasing the size of the economic pie, fails to make it big enough to generate both more wealth and more effective government policies. The question is and always must be the degree to which the private sector’s efficient but unequal distribution of wealth trumps government’s more equitable, less efficient, but popular economic programs.

Ruling is about staying in power, not about good governance. To this end, leaders buy support by rewarding their essential backers relative to others. Taxation plays a dual role in generating this kind of loyalty. First it provides leaders with the resources to enrich their most essential supporters. Second, it reduces the welfare of those outside of the coalition. Taxation, especially in small-coalition settings, redistributes from those outside the coalition (the poor) to those inside the coalition (the rich). Small coalition systems amply demonstrate this principle, for these are places where people are rich precisely because they are in the winning coalition, and others are poor because they are not. Phillip Chiyangwa, a protégé of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, has stated it bluntly, “I am rich because I belong to Zanu-PF [Mugabe’s ruling party].”2 When the coalition changes, so does who is rich and who is poor.

Nor is Zimbabwe an isolated case. Robert Bates, a professor of government at Harvard University, described the link between wealth and political backing in Kenya:

I recall working in western Kenya shortly after Daniel Arap Moi succeeded Jomo Kenyatta as President of Kenya. With the shift in power, the political fortunes of elite politicians had changed. As I drove through the highlands, I encountered boldly lettered signs posted on the gateways of farms announcing the auction of cattle, farm machinery, and buildings and lands. Once they were no longer in favor, politicians found their loans cancelled or called in, their subsidies withdrawn, or their lines of business, which had once been sheltered by the state, exposed to competition. Some whom I had once seen in the hotels of Nairobi, looking sleek and satisfied, I now encountered in rural bars, looking lean and apprehensive, as they contemplated the magnitude of their reversal.3

Needless to say, people want to be sleek and satisfied and not lean and apprehensive. That is why they remain loyal. A heavy tax burden emphasizes the differences between being rich and poor—in or out of the coalition. At the same time, the resulting revenues fund spoils for the lucky few, leaving little for everyone else. Further, the misery such heavy taxes inflict on the general population makes participation in the coalition even more valuable. Fearing exclusion and poverty under an alternative leadership, supporters are all the more fiercely loyal. They will do anything to keep what they have and keep on collecting goodies. Gerard Padró i Miguel of the London School of Economics has shown that the leaders of numerous African nations tax “too” highly (that is, beyond the maximum revenue point) and then turn around and provide subsidies to chosen groups. This may be economic madness, but it is also political genius.4

Democrats tax heavily too and for the same reason as autocrats: they provide subsidies to groups that favor them at the polls at the expense of those who oppose them. We will see, for instance, that Democrats and Republicans each use taxation when they can to redistribute wealth from their opponents to their supporters. So democratic governments also have an appetite for taxation but they cannot indulge that appetite to the extent autocrats can. Since their numbers are small, an autocrat can easily compensate his essential backers for the tax burden that falls on them. This option is not available to a democrat because his number of supporters is so large. Tax rates are therefore limited by the need to make coalition members better off than they can expect to be under alternative leadership. On the campaign trail, US president George H. W. Bush told the American people, “Read my lips, no new taxes.” Yet, budget shortfalls left him scrambling for revenue. The result was more taxes. In the wake of the First Gulf War, just eighteen months earlier, Bush had approval ratings of over 90 percent. But a declining economy and his broken promise on taxes led to his ouster in the 1992 election. While all leaders want to generate revenue with which to reward supporters, democratic incumbents are constrained to keep taxes relatively low. A democrat taxes above the good governance minimum, but he does not raise taxes to the autocrat’s revenue maximization point.

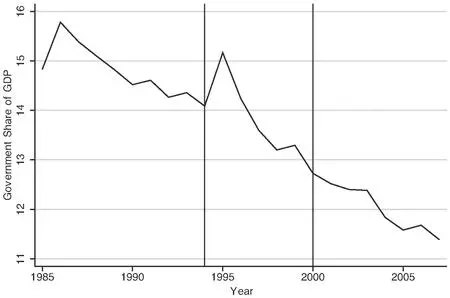

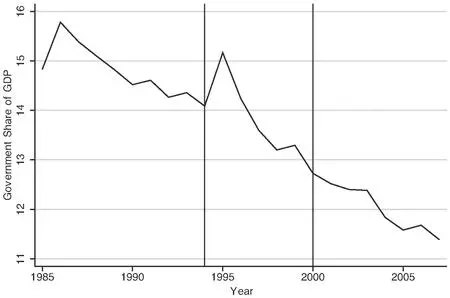

The relationship between regime type and taxation can be seen in the recent history of Mexico. Mexico’s first free election came in 1994, and the incumbent party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), lost nationally for the first time in 2000. As can be seen in Figure 4.1, onset of competitive elections (and of democratization) marks the start of the decline in government revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). As the size of the winning coalition enlarged, Mexico’s tax rates followed suit by declining, just as they should when politicians need to curry favor with many instead of a few. For instance, the highest marginal tax rate in Mexico in 1979, with the PRI firmly in control, was 55 percent. As the PRI’s one-party rule declined, so did tax rates. By 2000, marking the first truly free, competitive presidential election, Mexico’s highest tax rate was 40 percent.5

Members of any autocrat’s small coalition also dislike paying taxes, but they readily endorse high taxes when those taxes are used to funnel great wealth back to them. This was just the case in Bell, California. City Manager Robert Rizzo raised property taxes. The city council could have stopped such increases, but had they done so, the city could not have afforded their bloated consultancy fees. Suppose for simplicity that Rizzo’s coalition was composed of 1 percent of Bell’s 36,000 residents. For every dollar increase in tax per person, Rizzo would have had up to $100 of services and payments he could transfer to each coalition member. Had his coalition been composed of half of Bell’s residents, each dollar increase in tax would provide only $2 per coalition member for transfers and services. It is easy to see why the coalition would sooner endorse higher taxes in the former setup than the latter.

FIGURE 4.1 Mexico’s Tax Take and Democratization

Nevertheless, to most of us who live in democracies, the idea that our taxes are actually less than in other systems might sound frankly absurd. If you live in New York City, as we do, you pay federal, state, and local taxes (as well as social security, Medicare, and sales tax). If you earn a reasonably good income, then income taxes suck up about 40 percent of your earnings. By the time you factor in sales, property, and other taxes, a reasonably wealthy New Yorker will have paid more than half her income in tax—hardly a low figure. European democracies, with their extensive social safety nets and universal health care, can tax at even higher rates. In contrast, some autocracies don’t even have income taxes. But the comparison of average tax rates is misleading.

Читать дальше