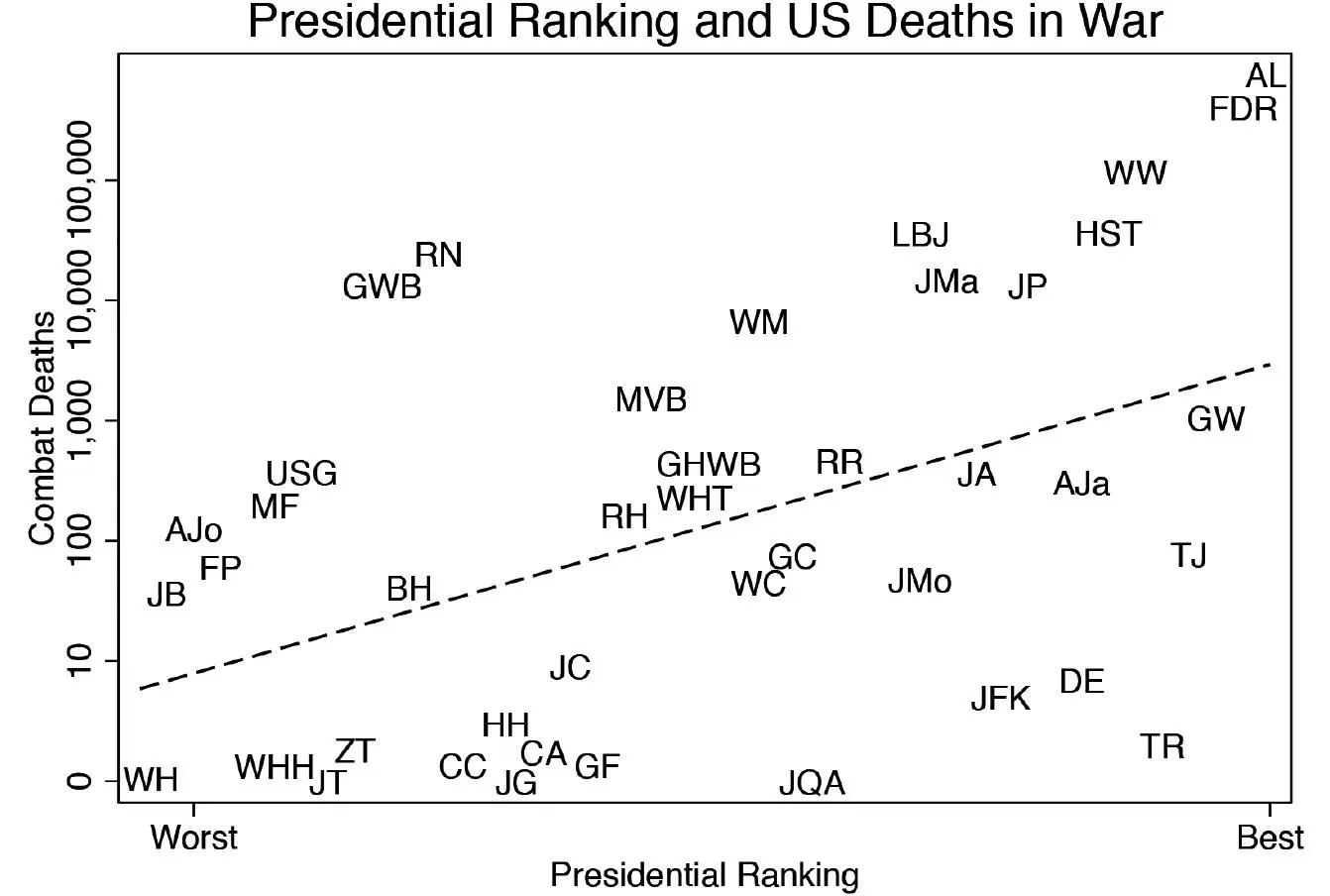

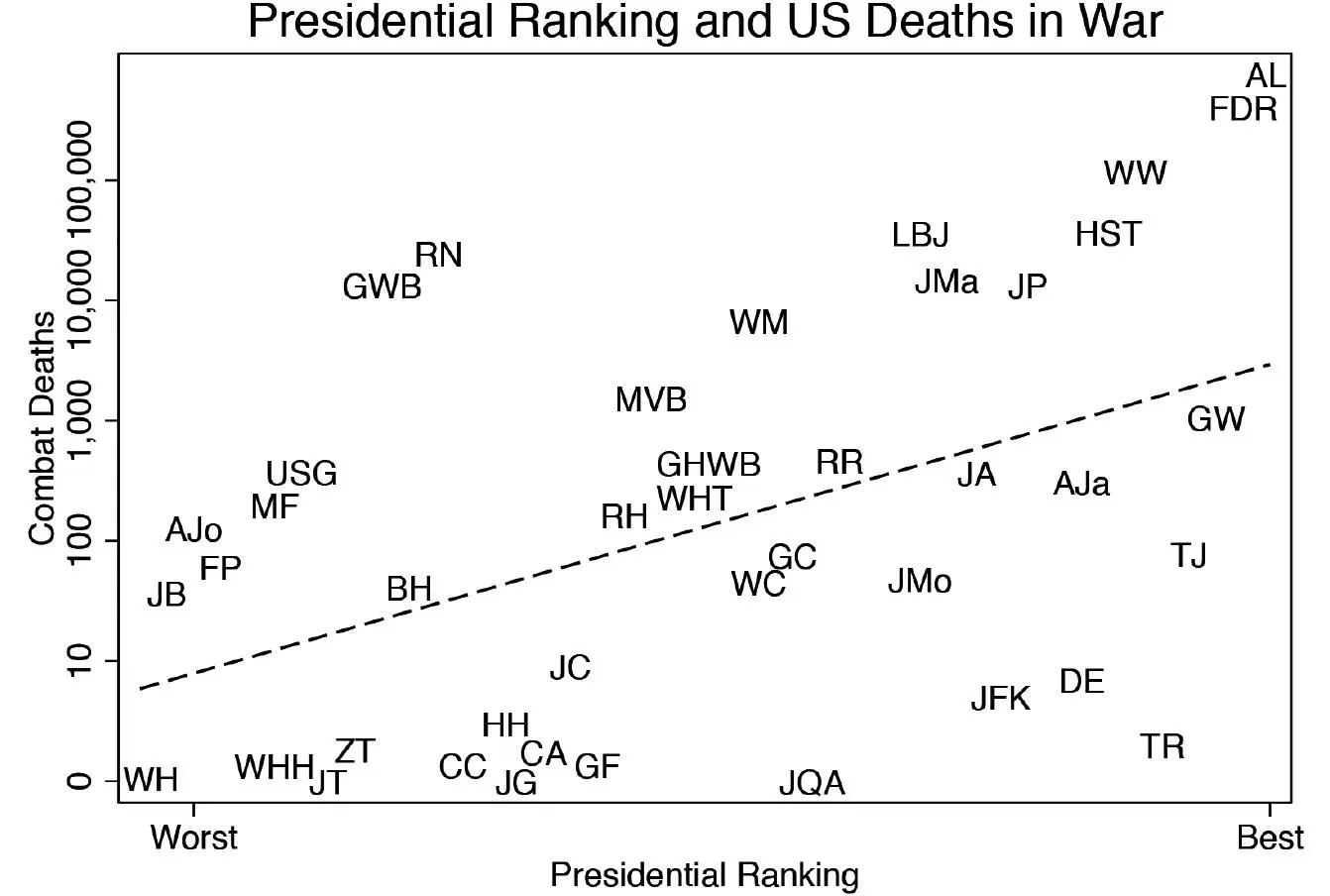

Figure I.1. Presidential Rankings and War’s Grim Reaper

Most of the top presidents, those who have enjoyed the greatest fame and honor among historians, indeed gained fame and honor during times of war. Correlation, of course, is not the same as causation. Just because many died in wars during the time of the best-rated presidents is not proof that war deaths are good for presidents or are even the source of the high regard in which historians hold them. That is what the rest of this book investigates. For the moment, however, we should acknowledge that while correlation most assuredly does not equal causation, the presence of correlation at least encourages the search for an explanation that can rise to the level of a causal account, the task in the chapters that follow.

It is noteworthy that among presidents who presided over heavy US losses in wartime, only George W. Bush ranks in the bottom ten. He apparently believes that history will judge him more kindly than do his contemporaries. If history, as reflected in our graph, is accurate, he may well be right. The remainder of the bottom group is made up of men who, on average, oversaw the deaths in war of less than ninety Americans each. Four were president during a time that zero Americans died in war and only one of these can be explained by an utter lack of opportunity (William Henry Harrison died just one month after taking office). Despite their records of successfully avoiding many American war deaths during their time in office, only two of the bottom ten presidents in ranking were reelected: George W. Bush and Ulysses S. Grant. Bush, as we have already noted, is the exception in this bottom group—he did preside over a lot of war deaths. Grant’s fame and rise to the presidency was, of course, on the back of his policy of throwing his own soldiers into the Civil War’s death cauldron on the principle that the Union had a bigger population, and so could afford more losses than the Confederacy. While Grant had few war deaths during his presidency to bolster his standing, we must acknowledge that but for the vast war deaths to his account, he surely would never have been president. The rest of the bottom-ranked presidents got one term or less, some having inherited the presidency and having failed to win election on their own.

Among the top presidents, there are exceptions to the pattern the graph shows of deaths translating into high regard by historians. George Washington (GW), Thomas Jefferson (TJ), Andrew Jackson (AJa), Teddy Roosevelt (TR), and Dwight Eisenhower (DE) rank among the ten most highly regarded American presidents and yet they all fall below the projected line of expected deaths associated with their ranking. Among them, however, only Teddy Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson were not famous US generals who presided over many deaths in war before becoming president. Jefferson, of course, was a revolutionary leader during the American Revolution. And, let’s be honest, Roosevelt was a prime mover and shaker behind the United States’ decision to go to war against Spain in 1898. Not only was he a big promoter of that war; he also went to fight in it and, being a wealthy man positioned to garner attention, he became hugely popular because of the exploits of his “Rough Riders” and their charge up San Juan Hill. Without those “heroics” (and the desire to neutralize his expected future political impact), McKinley might never have chosen him to be his vice president. Washington and Eisenhower are part of a very exclusive club of military officers in America’s history to be ranked as general of the army (in Washington’s case, the rank not having existed in his lifetime, he was elevated to that rank posthumously in 1978). Both, of course, presided over lots of war deaths in their prepresidential years. Their role in war, like Grant’s, is how they got to be president.

We should not be in the least surprised to learn that more highly regarded presidents were more likely to win a second term in office. That, after all, is what elections should produce. Those deemed most successful should be retained the longest. Perhaps more surprisingly—certainly more depressingly—those who oversaw more deaths on an average annual basis, even taking population growth into account, were particularly likely to be rewarded with a second term. Having avoided deaths in wartime practically guaranteed that the president would not get a second term. Of the ten presidents who oversaw no US deaths in war (several of whom were famous generals who, doing their jobs faithfully, presided over plenty of deaths before rising to the presidency), only one managed to be in office for more than four years. That was Calvin Coolidge, a president barely thought of today except, perhaps, as the butt of a Dorothy Parker joke: on learning that Coolidge died, she exclaimed, “How can you tell?”30 Depressingly, we seem to have so little regard for presidents who give us peace that those who oversaw US deaths in war averaged more than six years in office, whereas those who oversaw no deaths averaged fewer than three years.

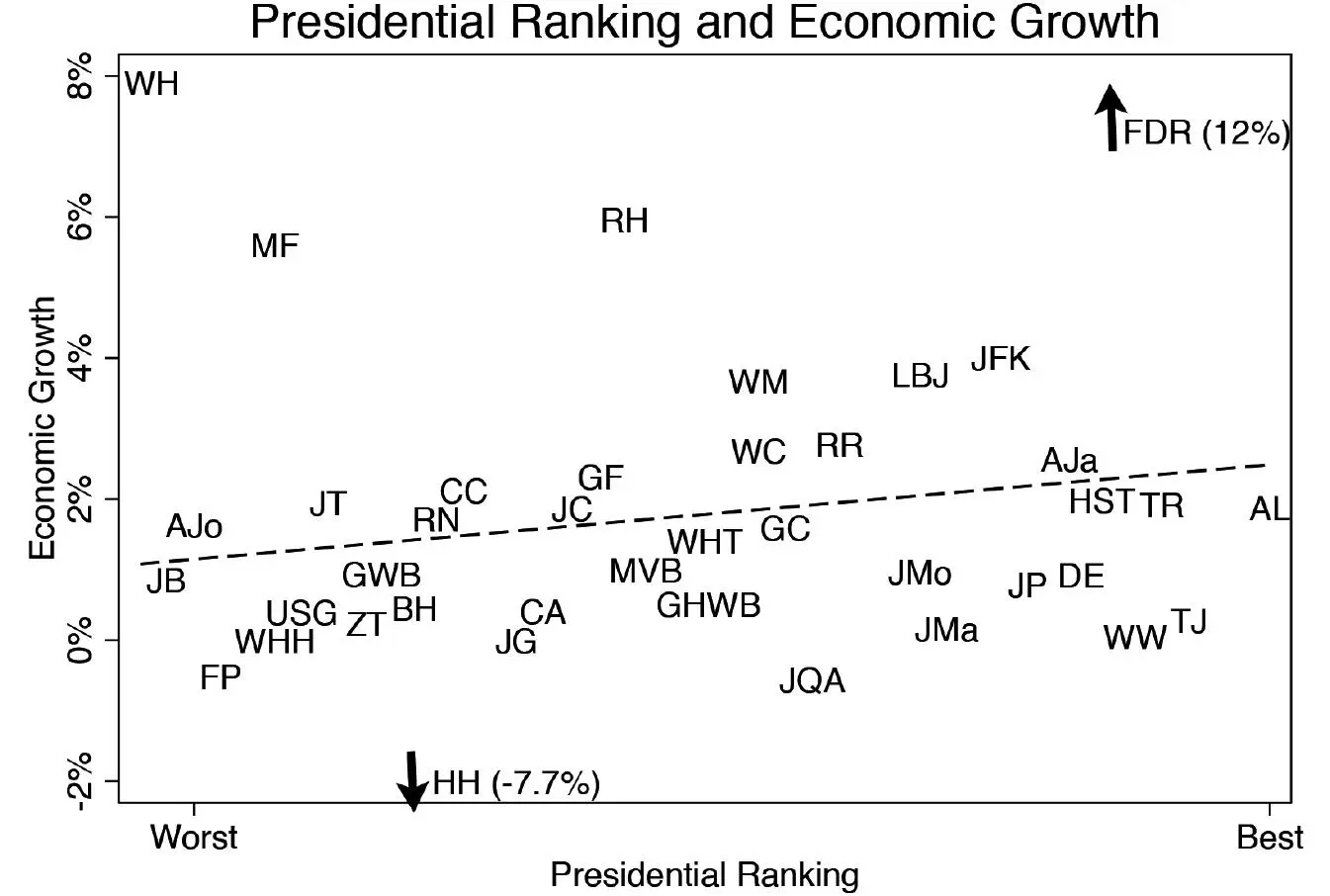

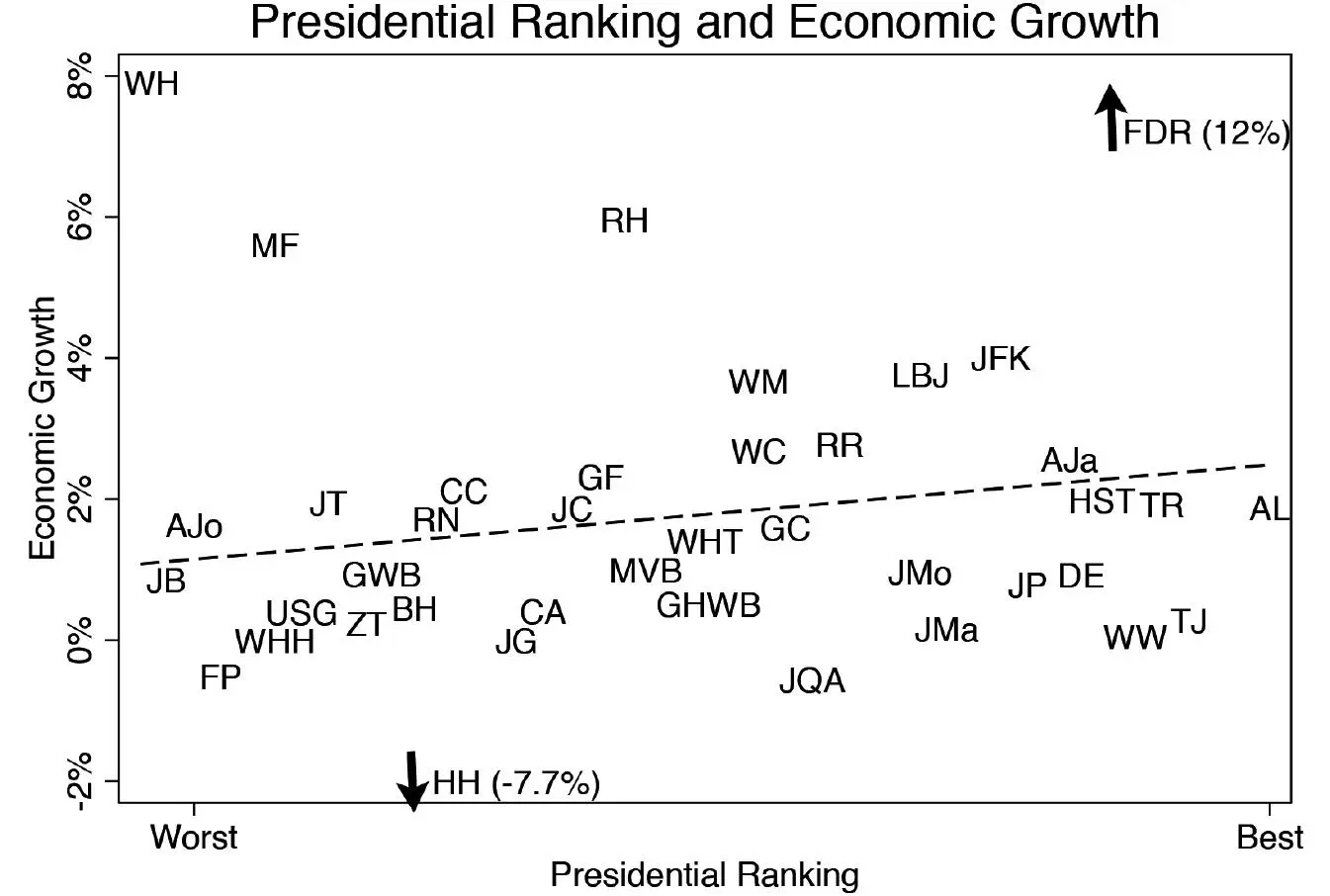

Contrast Figure I.1 on rankings and war deaths to Figure I.2. Here we see the effect—or rather the lack of effect—that presiding over prosperity has on a president’s standing among historians. In this figure, the dotted line reflects the statistically predicted response of ranking to annual per capita income growth under each president. We would like to think that presidents who preside over growth in prosperity are especially well regarded and likely to win reelection. Alas, that is not the case. Presiding over prosperous times has no consequential bearing on where a president stands in the hindsight of history.

Figure I.2. Presidential Rankings and American Prosperity

The second figure reminds us that FDR, who, after inheriting the Depression, restored prosperity through the mobilization for war, not only ranks near the top in annual war deaths during his time in office, but also in annual growth in income. But after him, the next three top presiders over economic growth—we are careful not to attribute growth to or against their economic policies since, after all, all presidents claim credit if the economy does well in their time and cast blame on others if it performs poorly—are Warren Harding (WH), Rutherford B. Hayes (RH), and Millard Fillmore (MF), ranked 43 out of 43, 25th, and 38th respectively. So much for a belief that prosperity produces a great legacy! Apparently it was much better for a president’s legacy and his reelection to oversee death than to oversee growth. We will have a look, in the final chapter, at which presidents were best both at minimizing US war deaths and increasing the nation’s per capita income.

Yesteryear’s Lessons for Today

MADISON’S FEAR OF EXECUTIVE POWER TO MAKE WAR HAS BEEN proven correct. Unbothered by the limitations imposed in Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution that gives Congress alone the right to declare war, American presidents have often gone about the business of fighting wars on their own, and presenting Congress with a fait accompli. All too often, as we shall see, they did so at least as much because it served their interests as because it served the interests of the nation. That is as worrisome and relevant to the selection of the president and members of Congress in our time as it was throughout US history. Hence, in examining the personal motives of the president and the Congress in past crisis situations, we hope the reader will learn what remains relevant today. To help in that process, we highlight in the concluding chapter what we believe are some important contemporary lessons.

Читать дальше