We have already indicated that Obama could have left Putin with greater uncertainty about his intentions or about the strength of a US response to Russian expansionist undertakings. Obama could have promoted such uncertainty simply by having insisted on pushing the French UN Security Council resolution to a vote. Instead, his failure to act left it clear that he was not prepared to pay the price to militarily oppose Putin’s expansion. Given that the military option was off the table—and Putin knew it—we investigate what other policy levers Obama might have used to improve outcomes (from the US perspective).25

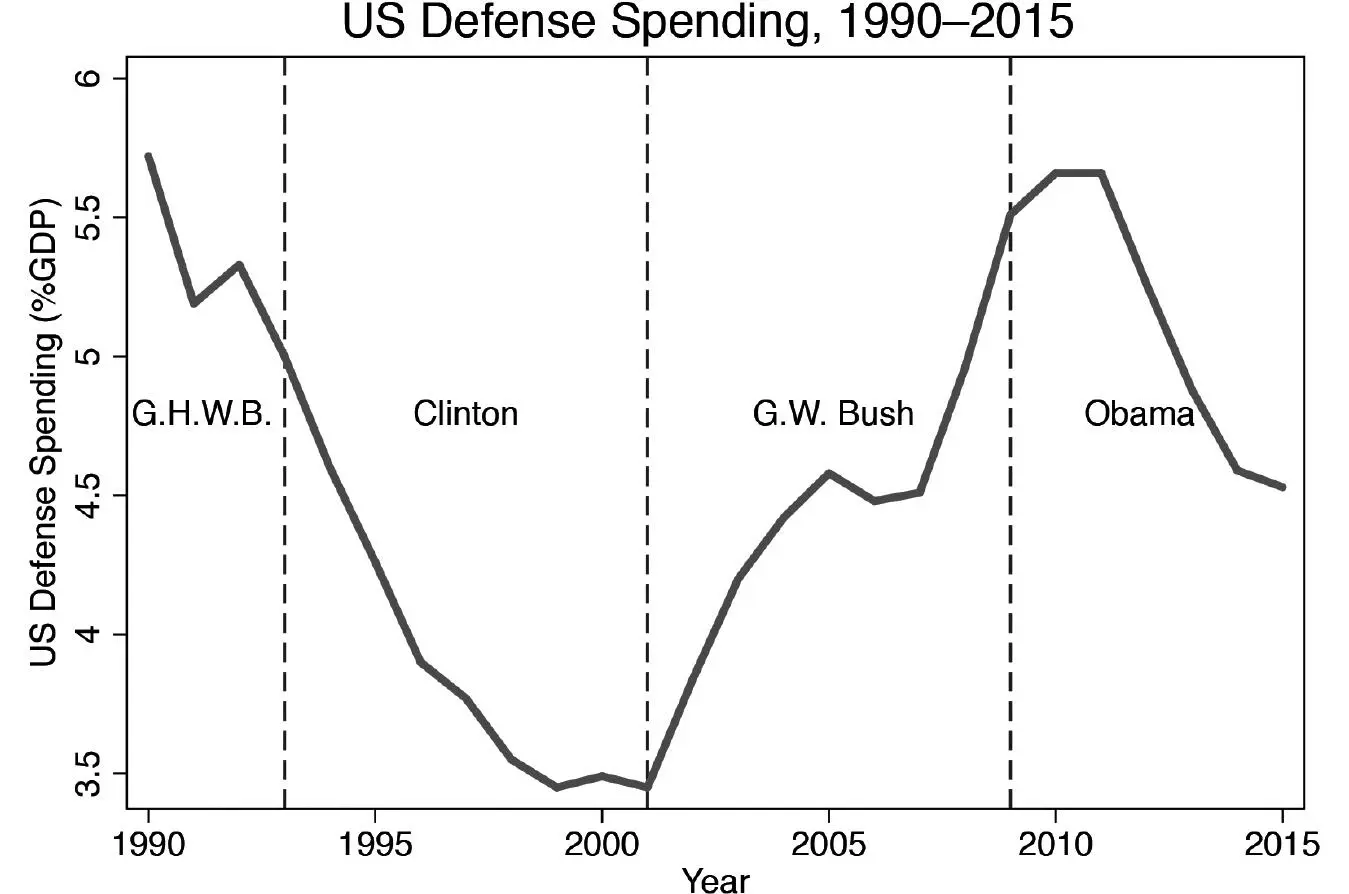

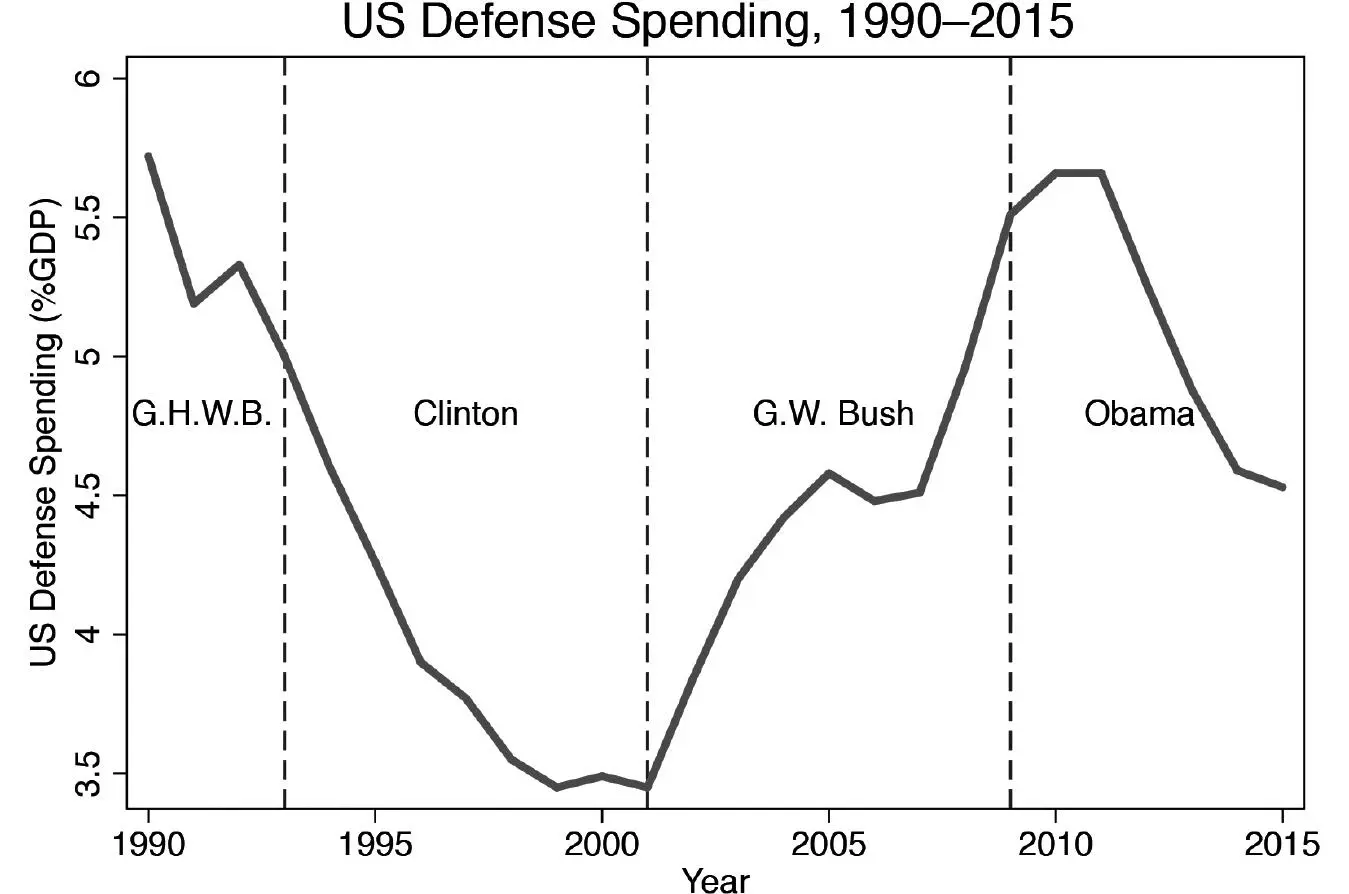

Figure 6.2. US Defense Spending from the End of the Cold War to 2015

Once a leader disavows the military option, his or her ability to influence international events is limited, but it is not zero. Presidents still have the choice of sanctions and foreign aid—the sticks and carrots of foreign policy. President Obama used both tools to influence events in the Ukraine, but he could have used foreign aid more efficiently.

In March 2014 he issued a series of executive orders to impose sanctions on Russia in the wake of its involvement in the Ukraine.26 The usual problem with imposing sanctions, beyond that they rarely work, is that they signal that a leader is not willing to do more. As discussed, Obama’s (in)actions over Syria had already revealed his passive approach—so, no harm done there. Further, the sanctions were designed to maximize their political effect. Although his efforts were far from perfect, he targeted sanctions to impose pain on the relatively small group of wealthy oligarchs to whom Putin is beholden, rather than on his domestic political opponents, thus applying additional political pressure.

Obama also used foreign aid to prop up the pro-Western government in Ukraine. Here we believe his policy was misguided. In March 2014, Congress authorized $1 billion of aid to Ukraine. This aid was part of a $40 billion package of aid and financial support from such organizations as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. The aid did not come without restrictions. For instance, the Ukrainian parliament was required to make legislative changes in the banking and energy sectors so as to receive some of the funds.27 However, the aid conditionality did not include political reforms. No one in the Obama administration seemed to ask why so many people in East Ukraine preferred to be Russian rather than Ukrainian. Before releasing aid, Obama could have insisted on real democratization that included institutionalized protections for ethnic Russians in Ukraine, but he did not. Instead the aid enabled the pro-Western government of Petro Poroshenko to survive unreformed and to perpetuate Petroshenko’s policies, giving Putin the excuse he needed to invade.

Over 8 million Ukrainians, about 17 percent of the total population, identify themselves as ethnically Russian. These citizens were disproportionately concentrated in Crimea and East Ukraine and faced discrimination. By failing to enact legislation and reforms to protect this minority, the Kiev government ensured that ethnic Russians remained alienated.

The United States and European Union nations favored the incumbent pro-Western Ukrainian government that came to power following the deposition of Viktor Yanukovych due to popular protest over his policies to reject agreements with the EU and align instead with Russia. Hence, the West gave aid to prop up the subsequent government of Petro Poroshenko and the pro-Western shift in policies that it enacted. Unfortunately, unconditionally supporting the Kiev government does little to resolve the underlying issues. Instead, we argue that Obama could have substantially weakened Putin’s position by making support for Kiev contingent on the Ukrainian government adopting policies and institutional reforms that promoted the interests of ethnic Russians in Ukraine rather than discriminating against them.

If Ukraine implemented institutional reforms that enshrined civil rights, such as freedom of speech and assembly; promoted a free media; and allowed effective political competition, then Russian-speaking Ukrainians would have wanted to be part of the Ukraine rather than part of Russia. Such true democratic reforms, rather than simply the presence of elections, would provide for the welfare of all citizens—those of Russian extraction along with ethnic Ukrainians.

True democracy is the set of governance rules under which winners need the support of many people, not simply a system in which elections occur. Retaining office under such circumstances is extremely difficult—it involves a relentless battle for good policy ideas and frequent political turnover. All leaders, if left to their own devices, prefer to restrict political competition so that their survival depends on a smaller group of backers. But in Ukraine, the exceptional circumstances that make leaders actually willing to really democratize are present: the government is new, broke, and facing mass protests and insurrection. Without financial support the government struggles to pay off supporters and fight Russian separatists. By providing aid unconditionally to the Poroshenko government, the United States allowed him to perpetuate the current form of government that discriminates against ethnic Russians. Such policies might have cost Poroshenko Crimea and parts of East Ukraine, but later they helped him retain power. Ukrainian leaders, like leaders everywhere, think about policy from the perspective of what is good for them and not what is good for the nation. And for a leader it might well be better to be firmly ensconced as head of half a country than to be out of power in a whole country. Hence, Poroshenko took US aid, perpetuated a relatively closed form of government, and accepted the loss of some of the country, while making efforts to limit such losses. A tolerable outcome for him, but one that was highly undesirable from the perspective of the average Ukrainian.

Suppose instead that the United States had withheld all aid to Ukraine until it passed and implemented laws enshrining a free press, the right to free speech, and other rules, including an independent judiciary, that promote genuine political competition. That would have put Poroshenko and his cronies in serious jeopardy of losing power. However, faced with a weakening economy and civil war and without financial support, deposition would have loomed as a real threat. By insisting on such changes before the delivery of assistance, Obama might have promoted genuine democratization in Ukraine, reduced the appeal of separation for ethnic Russians, and weakened the position and legitimacy of Putin to intervene in Ukraine.

Partisan politics more than national needs determine the extent to which presidents are willing to risk war. Kennedy needed to appear tough to avoid large losses in the House of Representative in the 1962 midterm elections and, of course, he acted to avoid the risk of impeachment. He was willing to embark on an aggressive course of action that, by his own estimates, put the United States at a high risk of nuclear war. The gamble paid off for him and the Democrats: Khrushchev backed down. In contrast, Obama’s supporters opposed US military engagement. He followed the political incentives, but by dithering over Syria and failing to hold Assad to account, he dealt Putin a free hand. It is impossible to state whether Kennedy’s hawkish strategy or Obama’s dovish approach is the better. Kennedy won concessions, but in the process risked nuclear annihilation. Obama, by contrast, avoided conflict, but in doing so gave international rivals the opportunity to exploit the United States. Reasonable people can disagree over whether the moral and financial costs of war are justified in a particular circumstance. What we know with confidence is that the personal and political costs are the ones that determine whether wars are fought.

Читать дальше