Furthermore, whereas Johnson was trying to pay for the war as it was fought by raising taxes, Bush put off paying for the war, thereby avoiding the alienation of his voters. The financial burden of the war was only to come crashing down on the economy with the start of the recession, in the twilight of Bush’s time in office.

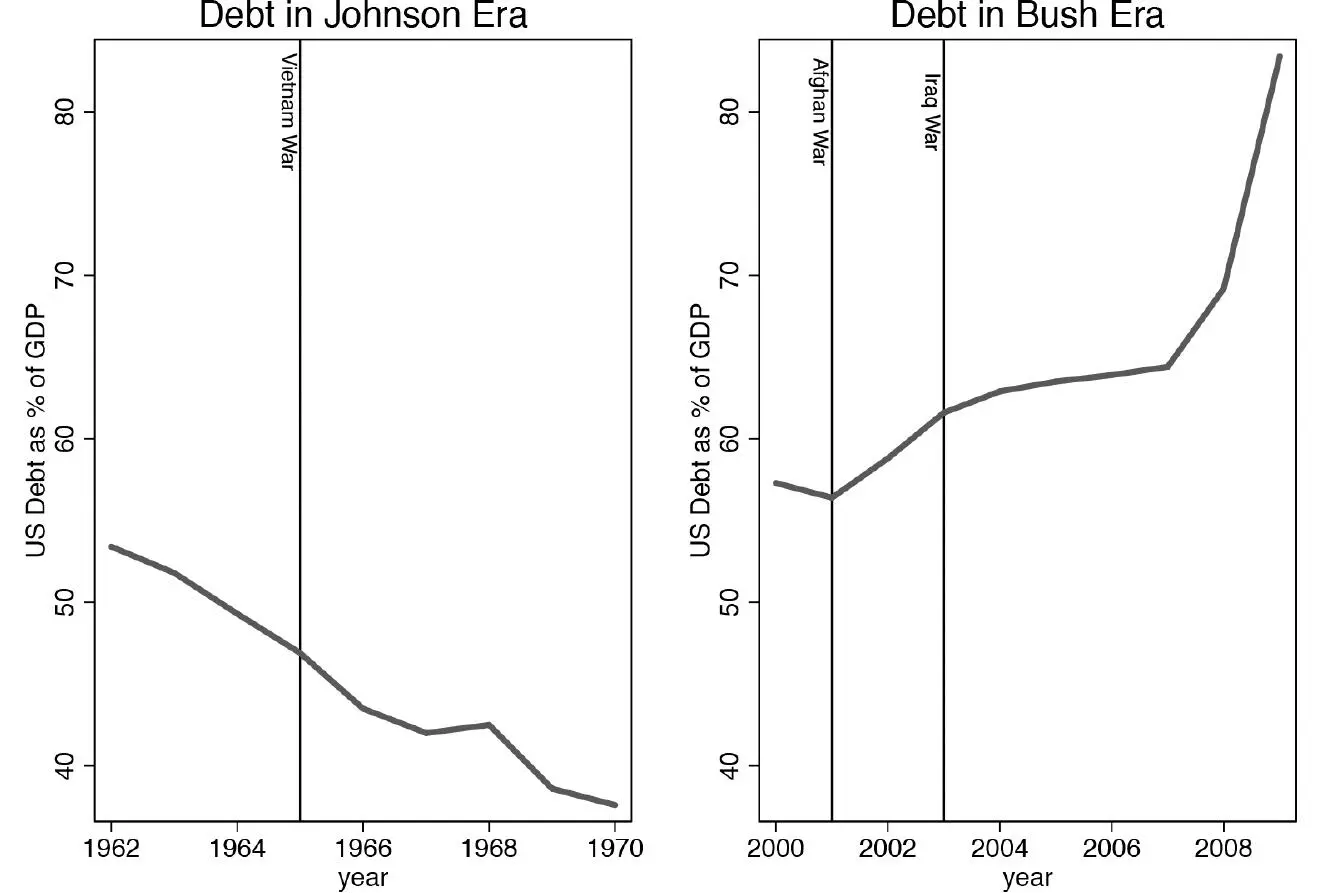

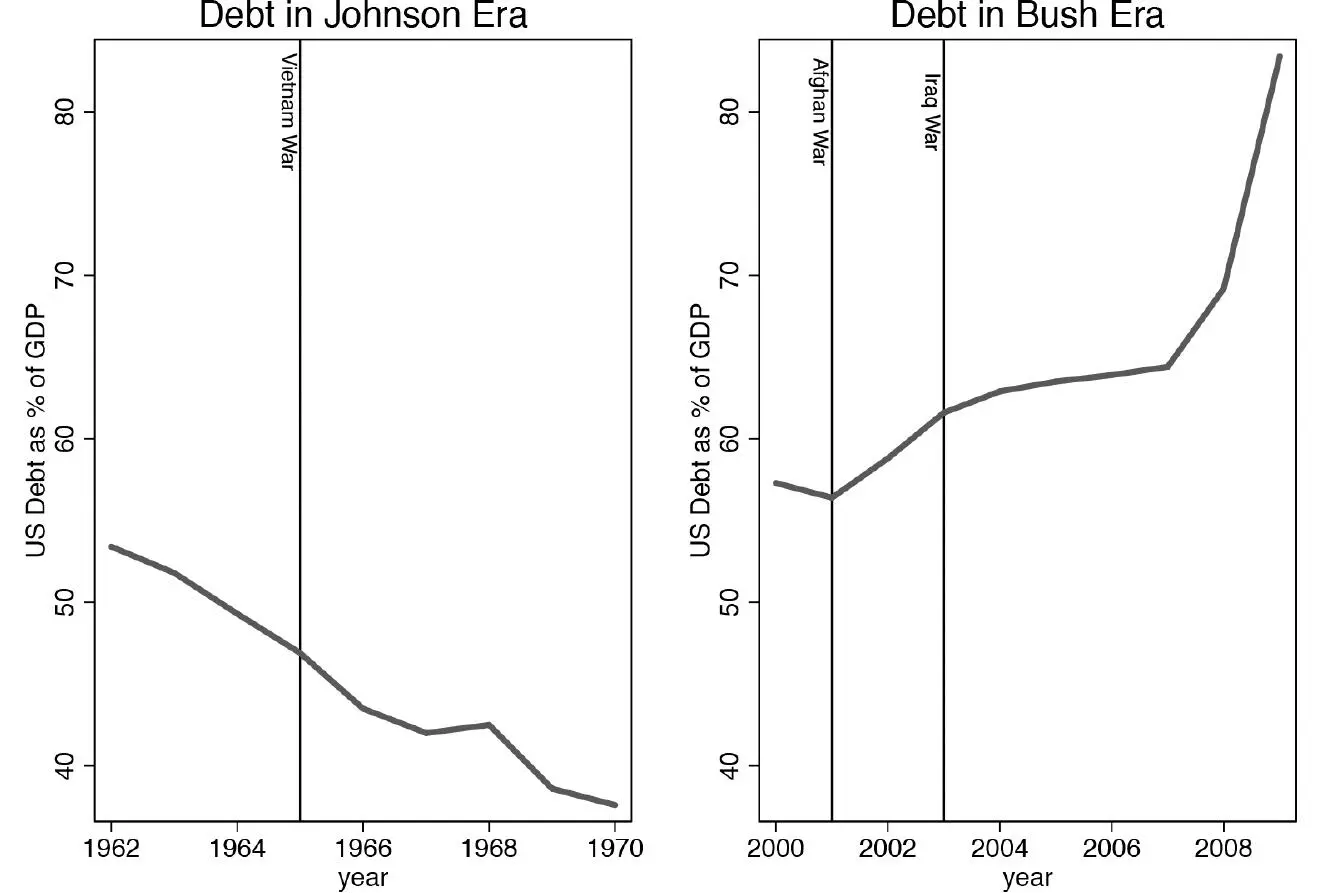

Figure 5.5 gives us another view of the differences in how the Vietnam and Iraq Wars were paid for. On the left we see the US debt during Johnson’s years in office. The debt shrank persistently throughout the years he was in office with only a slight upward burp in 1968, immediately replaced by a resumed downward trend. Not only was he taxing everyone to pay for the war, but between his tax policy and national economic performance, the vast cost of the war was not accumulating as a debt for future generations. Johnson’s Vietnam War was paid for as it happened. Conversely, Bush’s Iraq War was not only accompanied by tax cuts, especially for the wealthier (read Republican) voters, but it was also funded through deficit spending. Bush’s policy pushed the costs of the war off, necessitating that they be dealt with during his successor’s term in office. Too bad he did not take seriously President Johnson’s admonishment to the Congress that we quoted earlier: “I warn the Congress and the Nation tonight that this failure to act on the tax bill will sweep us into an accelerating spiral of price increases, a slump in homebuilding, and a continuing erosion of the American dollar.”53 Sounds an awful lot like what happened in 2008, as the country faced the economic consequences of a war it had not paid for!

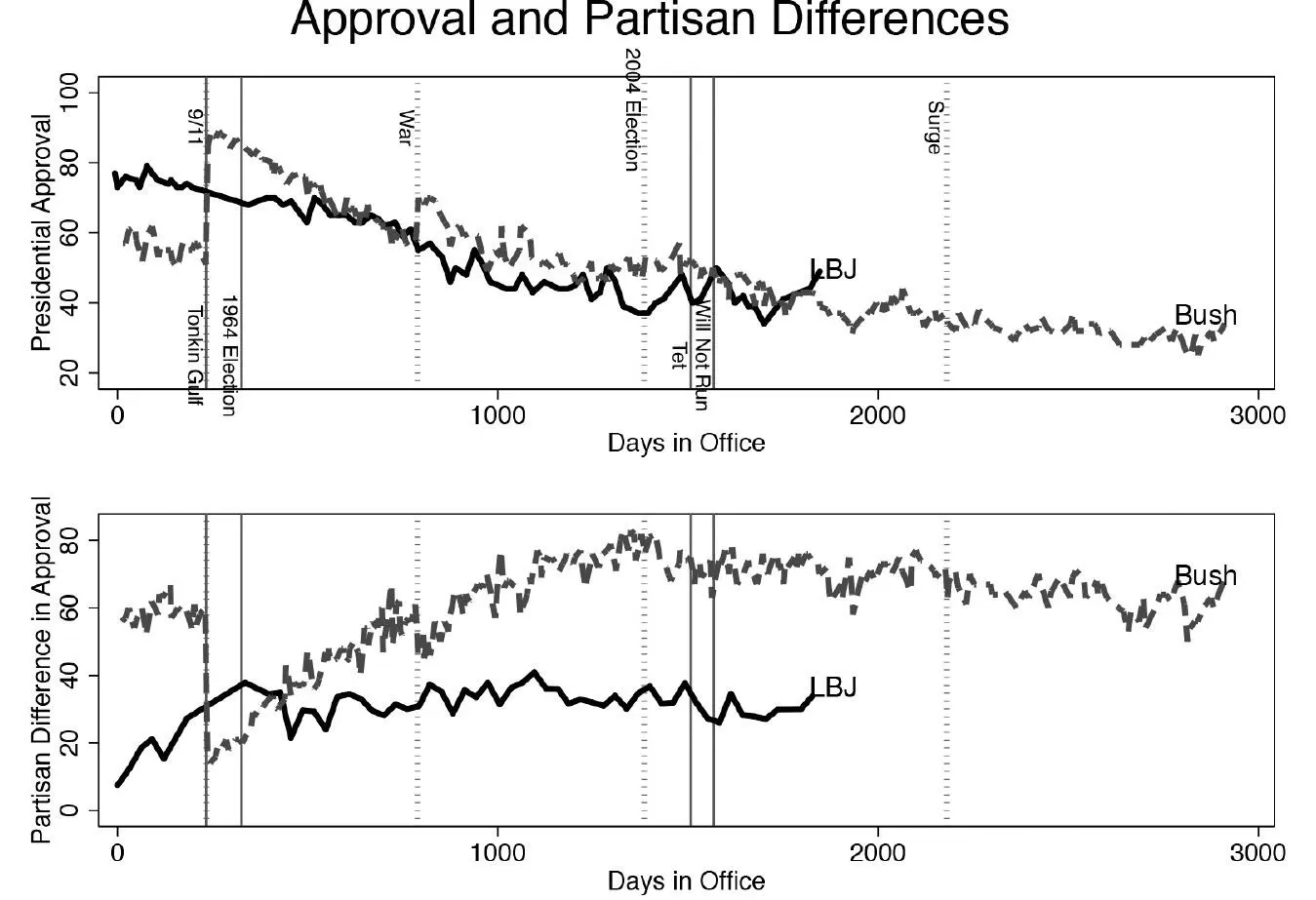

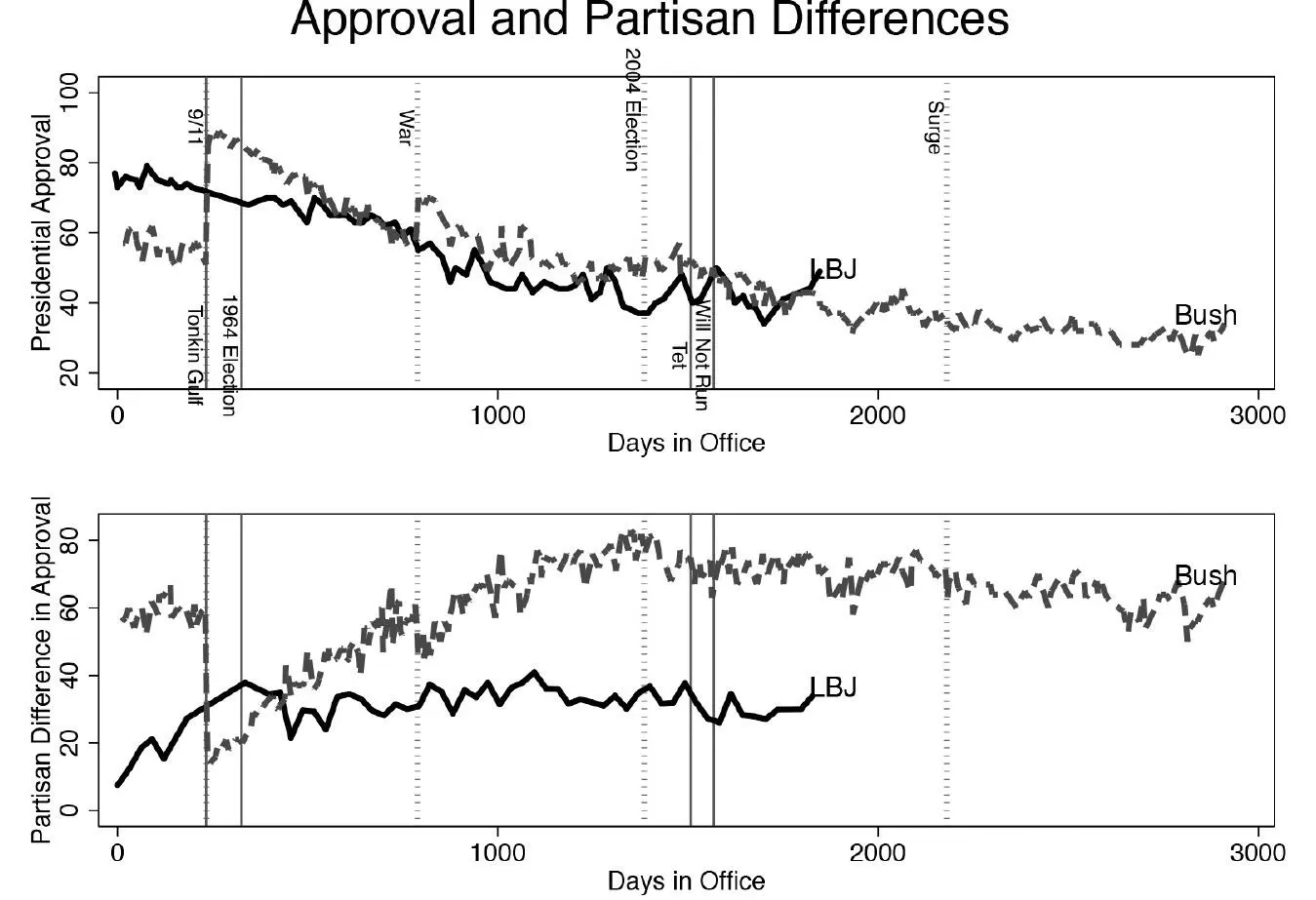

George W. Bush’s approach to war financing—buy now, pay later—helped him win reelection; Lyndon Johnson’s debit card approach—pay as you go—contributed to his inability to pursue reelection in 1968. The difference was not that one president was hugely popular and the other hugely unpopular. Rather, the difference was in the partisan spread in popularity. Figure 5.6 shows this clearly.

Figure 5.5. Indebtedness, Vietnam and Iraq

Figure 5.6. Partisanship and Presidential Approval: LBJ and W

We see in the upper panel that both LBJ’s and W’s approval ratings followed almost in lockstep. Approval declined over time, as is the common pattern for most presidents.54 Evaluations of Johnson’s approval rating, of course, end sooner than Bush’s, since Bush was president for nearly three thousand days and Johnson for less than two thousand. As we can see, Bush got a short-term burst in popularity following 9/11 and a smaller one at the outset of the Iraq War, but his approval trajectory, like LBJ’s, was inexorably downward. If we look at Bush’s equivalent time in office prior to the 2004 election as the number of days prior to the 1968 election at which Johnson announced he would not seek reelection, we see that Bush’s and Johnson’s approval ratings were nearly identical. So, differences in presidential approval do not help us understand why Bush succeeded in his reelection effort and Johnson abandoned his. Rather, the difference between the president who believed he could not be reelected and the one who was is evident from the bottom panel of the figure.

The bottom panel reports the difference in presidential approval by his respective partisans—Democrats in Johnson’s case and Republicans in Bush’s—and his opposition. As we should expect, Democrats were more approving of Johnson than were Republicans. At the outset, for Johnson, there was virtually no partisan difference in his approval ratings. This should not surprise us, as he assumed the presidency in November 1963 following John Kennedy’s assassination, an event that deeply shocked the nation. Once ensconced in his own right following the 1964 election, his approval ratings among Democrats were 30 to 40 percent higher than his ratings among Republicans, a figure that remained relatively stable throughout his presidency. The contrast to the partisan differences in voter approval for Bush could hardly be starker. When he took office, the gap between Republican and Democrat approval of the new president was around 60 percent and rising . . . until the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. On that horrific day and for a short time afterward, Republicans and Democrats rallied round the flag, giving the president very strong approval. By the time the United States went to war against Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, however, the partisan split in presidential approval was greater than it ever had been for Johnson. It was back to the level of partisan divide that had greeted Bush when he first assumed the presidency amid the hanging-chad controversy. From the onset of the Iraq War forward, for the remainder of Bush’s first term and his reelection, the partisan spread in approval hovered in the 70–80 percent range, falling below 60 percent briefly at the very end of Bush’s second term. That is, Republicans loved Bush; Democrats hated him.

Here in the difference in partisan divides we see almost the entire story of why two unpopular wars led to such radically different political outcomes. Johnson made Democrats and Republicans alike pay for his war. Bush pushed off paying for his wars, cutting taxes and cutting them least for likely Democrat voters while increasing the deficit, leaving the war to be paid for by his successor(s). Republican voters, having enjoyed a hefty reduction in their tax burden under Bush, looked the other way at the massive deficit he built up—a policy that they adamantly oppose when it is not accompanied by or caused by tax benefits for them—and gave him overwhelming support in his reelection campaign. Voters either loved him or hated him and which they did was strongly driven by their partisanship and, presumably, by their associated tax relief. As Vice President Joseph Biden observed of the massive debt the Obama administration inherited: “And, by the way, they [Republicans] talk about this Great Recession [as] if it fell out of the sky, like, ‘Oh, my goodness, where did it come from?’ It came from this man [Bush] voting to put two wars on a credit card, to at the same time put a prescription drug benefit on the credit card, a trillion-dollar tax cut for the very wealthy. I was there. I voted against them. I said, no, we can’t afford that. And now, all of a sudden, these guys are so seized with the concern about the debt that they created.”55 Of course, from the perspective of the Bush administration, what could be more perfect than getting a second term and then having someone else pick up the credit card bill? And from Johnson’s perspective, at least in hindsight, what could have been worse than paying for the Vietnam War as it was fought, thereby losing the chance of a second term?

We have seen who paid the financial costs of Vietnam and Iraq. But war entails other, deeper, more painful immediate costs beyond the out-of-pocket payment with dollars. War’s greatest cost is in the loss of life and life’s opportunities. We turn now to an assessment of who paid these costs in the cases of Vietnam and Iraq.

The Human Cost of War

CASUALTIES REDUCE SUPPORT FOR WAR. WE SAW THIS IN FIGURES 5.1 and 5.2. As US casualties climbed, more and more people thought that Vietnam and Iraq were mistakes. Certainly these broad trends show the correlation between US deaths and Americans’ opposition to war. Yet, people are generally very poor at conceptualizing the significance of statistics. They are much more sensitive to how events relate to them personally. The implication of US troop deaths is far more salient when it happens to family, friends, neighbors, or those in the local community. Citizens are more likely to oppose a war when those around them die or when they are personally exposed to danger. In the cases of Vietnam and Iraq, political scientists Scott Gartner and Gary Segura document the impact of casualties at this personal level. They examine local public opinion and voting records and show that voters from localities with disproportionately high casualties oppose wars and vote against incumbents. Voters from locales with few casualties remain more supportive of war. Headlines about national losses are hard for people to process and so they have less impact than the loss of local young adults: “all politics are local.”56

Читать дальше