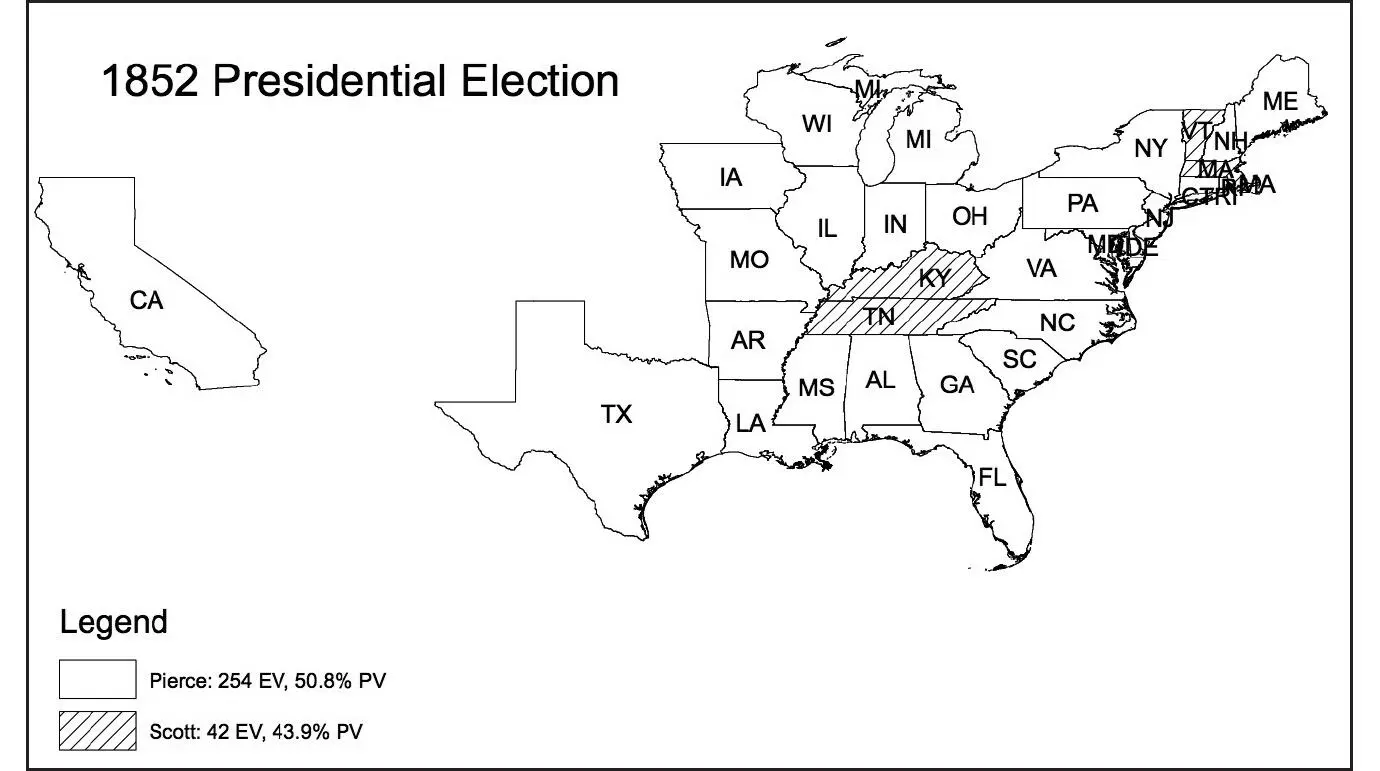

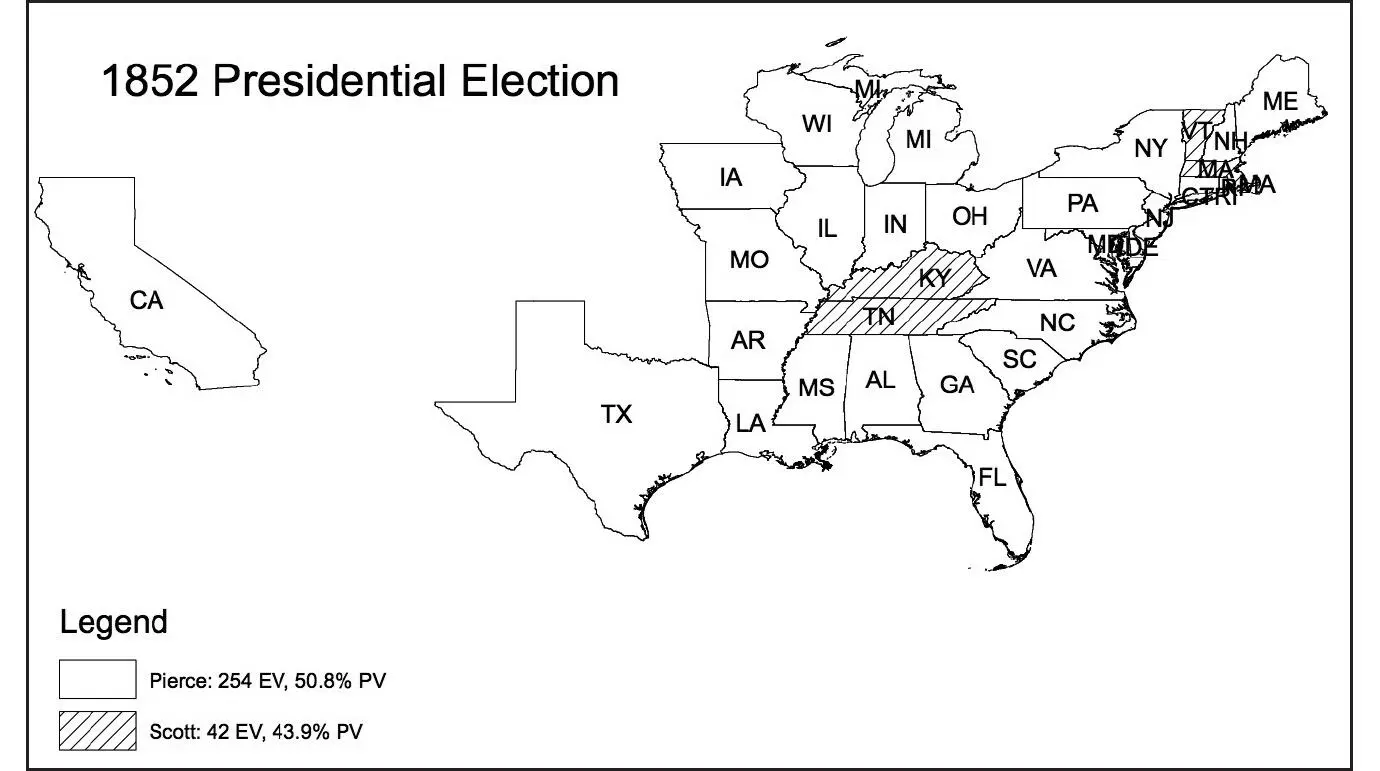

We begin with the 1852 election between Democrat Franklin Pierce and Whig Winfield Scott (later Lincoln’s first—failed—general in the Civil War). Senator John Hale of New Hampshire, whom we have already met, ran as well, as the candidate of the Free Soil Party, but he won no states and no Electoral College votes. Figure 3.1 shows the division of the Electoral College and the popular vote in that pre–Republican Party election. When we take a look at the 1856 and 1860 elections, we will want to remember what the 1852 map looks like. Before the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), the first presidential campaign of the antislavery Republican Party (1856), and the Dred Scott decision (1857), the presidential electoral map was not divided along sectional lines. Indeed, it was barely divided at all.

Figure 3.1. The Presidential Election of 1852

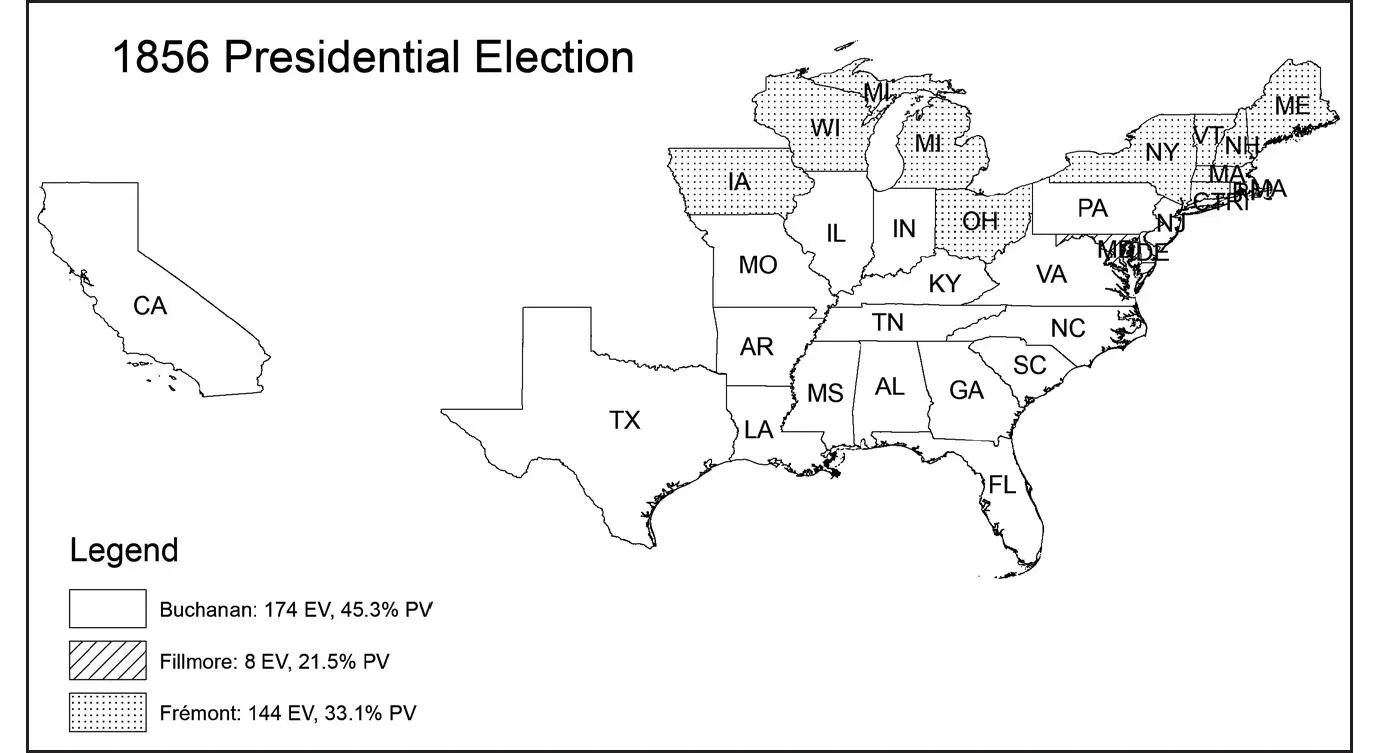

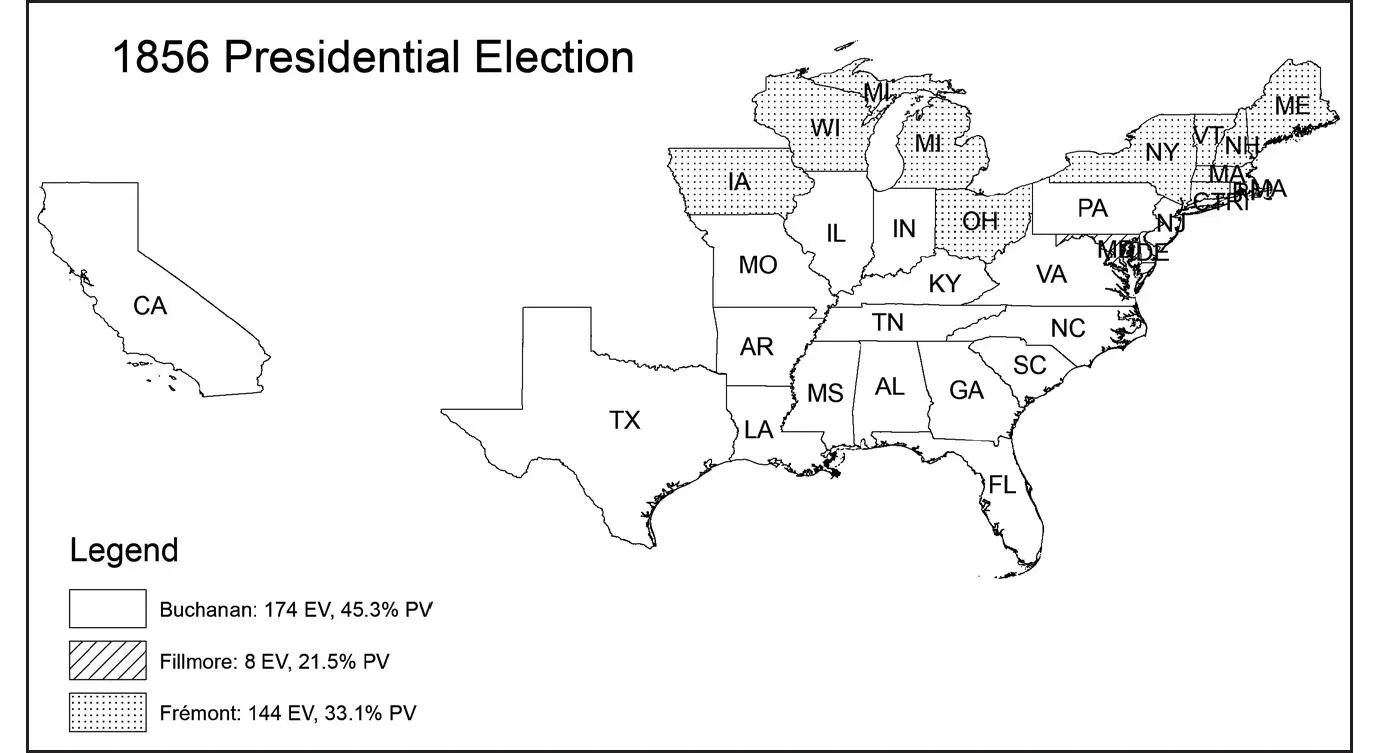

With the events just enumerated having happened and having reanimated the sectional battle lines that were prominent at America’s founding, the unity of the country was in doubt. We have to go back to the Andrew Jackson–John Quincy Adams election of 1828 (when Adams dominated in the New England states and Jackson just about everywhere else) to see anything resembling the clear sectional divide that was presented in the 1856 election, as seen in Figure 3.2.

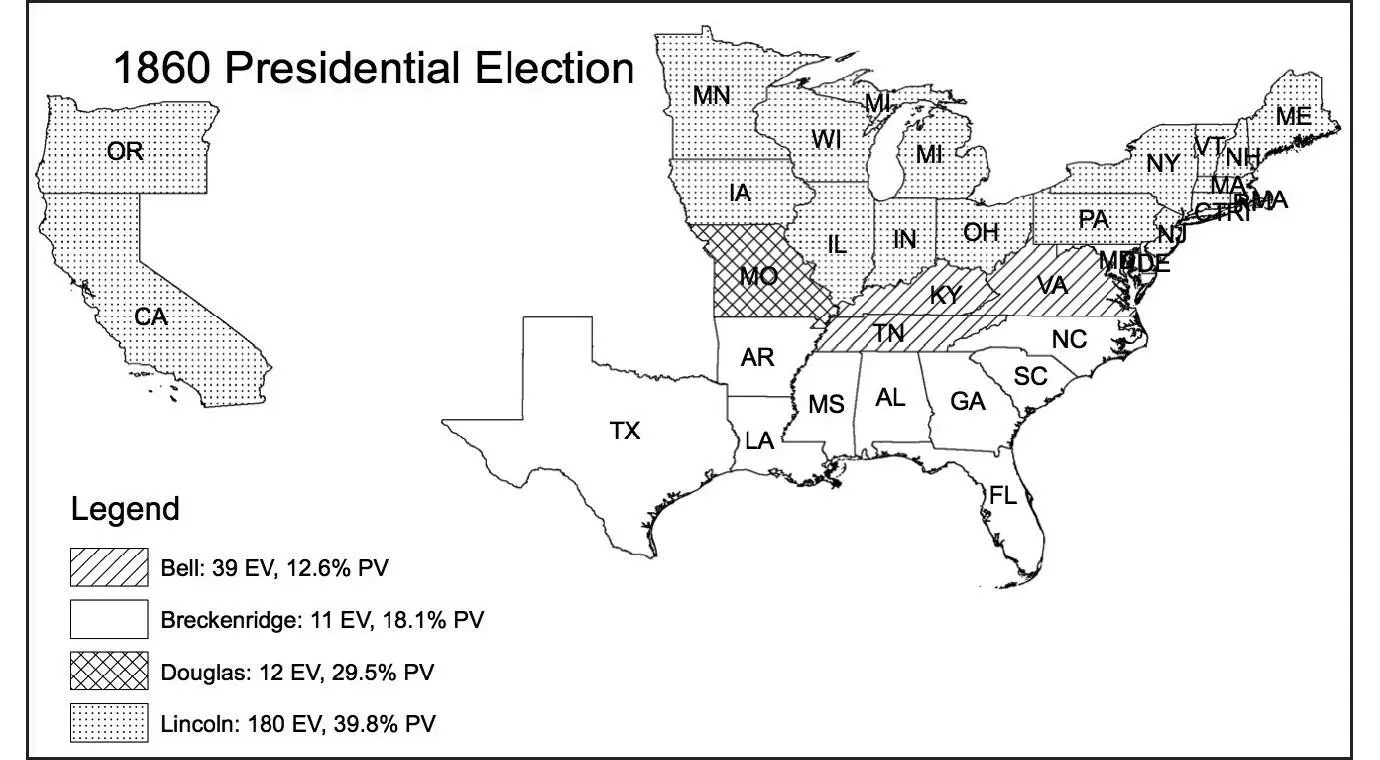

The Republican candidate, John Frémont, won 33 percent of the popular vote and 38 percent of the Electoral College vote. The entire South went for James Buchanan who, with a plurality of 45 percent of the vote (Millard Fillmore having won 22 percent) was elected president. Needing 149 electoral votes to win, Frémont fell short by only 55. This was a strong showing for a new party whose support was highly sectional. Frémont did not carry all of the North, but every state he won was in the North. To win in the future, the Republicans needed either to attract more votes or to deprive the Democrats of some of their successes. They could do this, for example, by dividing the Democratic Party’s vote among many candidates. As we saw, Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech coupled with the associated question he posed to Stephen Douglas did just that. This can be seen in the map of the 1860 election (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2. The Presidential Election of 1856

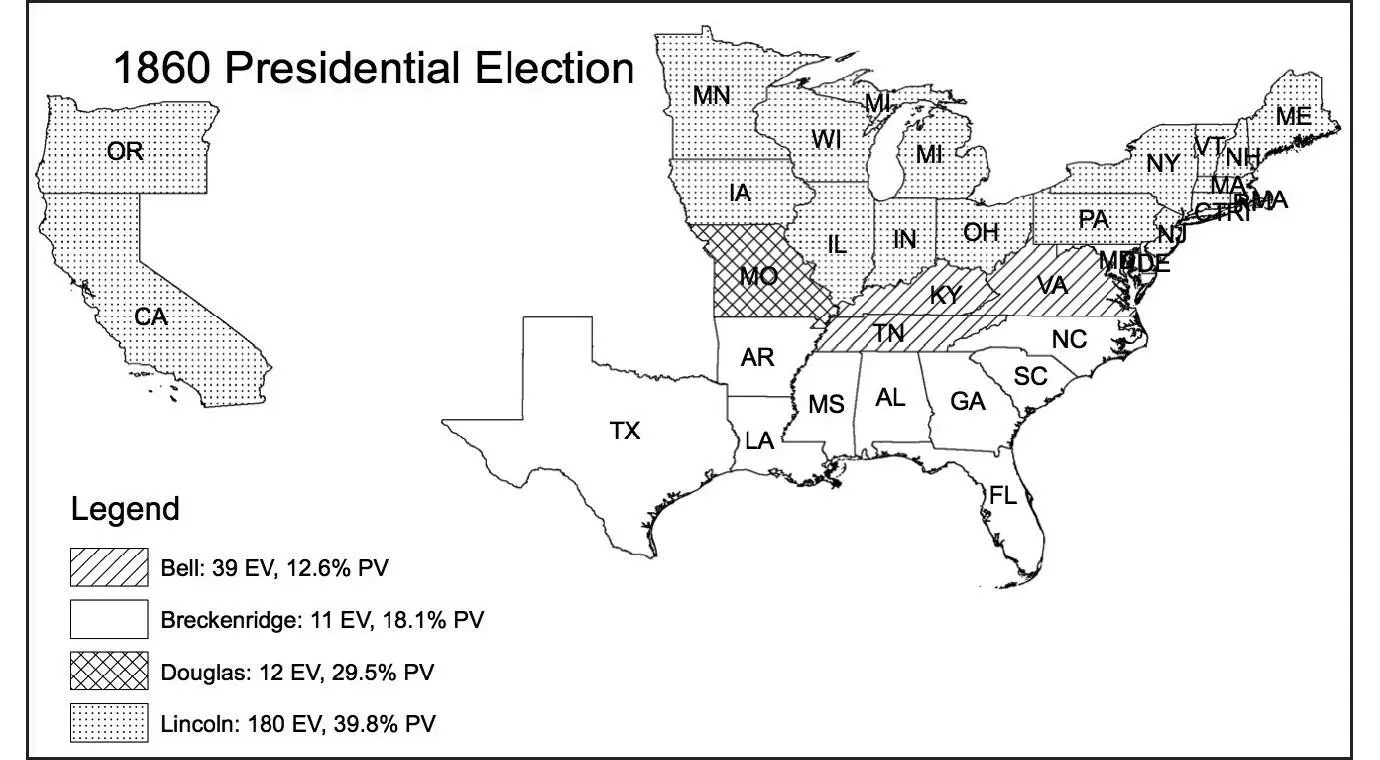

The Republican Party captured just less than 40 percent of the popular vote in 1860—better than Frémont had done—and they took 59 percent of the Electoral College vote, a solid majority. Douglas won almost no votes in the Electoral College (12) although he managed to secure 29 percent of the popular vote. This imbalance reflected the inefficient distribution of his electoral support and his inability to convert popular support into Electoral College clout because of deep electoral divisions within some states as well as across sections of the country. Where did the votes go? They went to Vice President John Breckinridge, who won the entire Deep South and to antisecession candidate Tennessee senator John Bell (who secured 13 percent of the popular vote and 13 percent of the Electoral College vote). This is crucial to reflect on. Breckinridge secured far fewer popular votes than Douglas and yet secured six times the Electoral College votes (72 compared to 12). Lincoln’s divide-and-conquer strategy really seems to have worked in 1860. A large portion of Douglas’s vote was dissipated, having been spread out in many states where he did not win. Furthermore, we can reasonably expect that a significant number of would-be pro-Douglas voters, seeing that the contest was really between the southern proslavery candidate Breckinridge and the antislavery Lincoln, voted strategically, giving their vote to Lincoln, who they would have seen as the lesser of two evils, thereby turning Lincoln votes efficiently into Electoral College votes.

Lincoln’s electoral efficiency was quite remarkable. He won the presidency with less than 40 percent of the popular vote while securing essentially no votes at all in most of the South where, in fact, he generally did not even appear on the ballot. The relatively moderate candidates on slavery—Douglas and Bell—did well in the border states but nowhere else. Lincoln managed to produce the house divided of which he spoke, a division not seen since 1828. In successfully splitting the national electorate, he dissolved the Democrats’ hold on the presidency. To be sure, as the 1856 map shows, the house was already divided electorally as soon as the Republican Party replaced the Whig Party. The difference was that Frémont ran against a united South and moderate antislavery middle that reached up to include such free states as Illinois, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Lincoln had made the contest much more sectional and divisive than it had been in 1856. To do so, he ran on a platform punctuated by critical issues that attracted support among antislavery voters, protariff voters, and Democrats disgusted by the divisions within their own party; divisions that Lincoln had worked tirelessly to foster. While some disgruntled Democrats undoubtedly turned to Bell or to Breckinridge, many, as we have noted, were likely to have voted for Lincoln rather than any of the former Democrats. Thus, Lincoln won in a significant number of states that Frémont lost, including the very swing states that party bosses had worried Seward might not carry (Seward being seen as more extreme on slavery and immigration—important questions in Pennsylvania and New Jersey—than Lincoln). Lincoln very narrowly won his home state (and Douglas’s) of Illinois (11 Electoral College votes), as well as Indiana (3), Pennsylvania (27), New Jersey (4), California (4), and the new states of Minnesota (4) and Oregon (3). And he was president!

Figure 3.3. The Presidential Election of 1860

Lincoln’s electoral campaign was accompanied by intensified threats of secession, followed by actual secessions during the lame-duck period when he was president-elect. Hence, it is important now to consider the views he held on secession and the actions he took to keep the Union together, his professed objective!

Views on Secession

THE THREAT OF SECESSION WAS NOT NEW TO LINCOLN’S ELECTION. From the country’s very earliest days it was an issue that presidents had to confront. As we saw in the Introduction and in Chapter 2, James Madison faced the threat of secession by the New England states.

As Lincoln the lawyer most assuredly knew, the Constitution of the United States provides for the entry of new states into the Union, but it seemed to be silent on the subject of withdrawal from the Union once a state’s people had ratified that document. Perhaps he reflected back on Jefferson’s own experience and thoughts. Jefferson, in his own way an extremist on constitutional questions, felt from the outset that the Constitution, like all laws, should be an ephemeral document. He believed that every generation had the right to define for itself the social contract under which it lived. Hence, he believed that

it may be proved that no society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation. They may manage it then, and what proceeds from it, as they please, during their usufruct. They are masters too of their own persons, and consequently may govern them as they please. But persons and property make the sum of the objects of government. The constitution and the laws of their predecessors extinguished then in their natural course with those who gave them being. This could preserve that being till it ceased to be itself, and no longer. Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right.35

Читать дальше