Martin Feinberg, Sam Gubins, Mary Jackman, Robert Jackman, Russell Roberts, Joseph Sherman, and Thomas Wasow discussed the ideas in this book with me and have given me the benefit of their insight and their friendship for many years. Equally, I have benefited from my friends and co-authors George Downs, James Morrow, Randolph Siverson, and Alastair Smith, who were my partners in developing some of the ideas that shape this book. Likewise, my friend and business partner, Harry Roundell, has been front and center in the analysis of many of the cases reported here and has been a source of deep and enduring support. My spring 2008 students—James Henry Ahrens, Jessica Carrano, Thomas DiLillo, Emily Leveille, Christopher Lotz, Kathryn McNish, Christian Moree, Deborah Oh, Katherine Elaine Otto, Silpa Ramineni, David Roberts, Andrea Schiferl, Jae-Hyong Shim, Jennifer Ann Thompson, Michael Vanunu, Stefan Villani, Paloma White, Natalie Wilson, Stefanie Woodburn, and Angela Zhu—and my spring 2009 students—Daniel Barker, Alexandra Bear, Katherine Cheng, Nour El-Dajani, Natalie Engdahl, Sanishya Fernando, Emily Font, Michal Harari, Andrew Hearst, Ashley Helsing, Tipper Llaguno, Veronica Mazariegos, Eric Min, Linda Moon, Shaina Negron, David Schemitsch, Kelly Siegel, Milan Sundaresan, Kenneth Villa, and Yang-Yang Zhou—served as willing guinea pigs who helped shape the chapter “Dare to Be Embarrassed!” All are innocent of responsibility for the remaining deficiencies in this book and each certainly helped eliminate many.

I am particularly grateful for the support of the Alexander Hamilton Center for Political Economy at NYU— The Predictioneer’s Game is the embodiment of its commitment to logic and evidence in pursuit of solutions to policy problems—and to Shinasi Rama, its deputy director, and to those whose generous support makes the Center possible, especially the Veritas Fund, the Thomas W. Smith Foundation, the Lehrman Institute, David Desrosiers, James Piereson, and especially Roger Hertog, without whom there could not be an Alexander Hamilton Center.

My colleagues in the Wilf Family Department of Politics at New York University and at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University are an endless source of support and inspiration. I could not have asked for better environments in which to pursue my research. Random House has been a terrific organization to work with, providing superb and subtle copyediting and bringing the highest standards to every aspect of this work. I thank them for their help.

Finally, I want to remember Kenneth Organski, my professor, coauthor, and friend, and the inspiration behind the original decision to apply my forecasting model to problems in the real world. He died too soon, but he left a legacy that will endure forever.

Appendix I

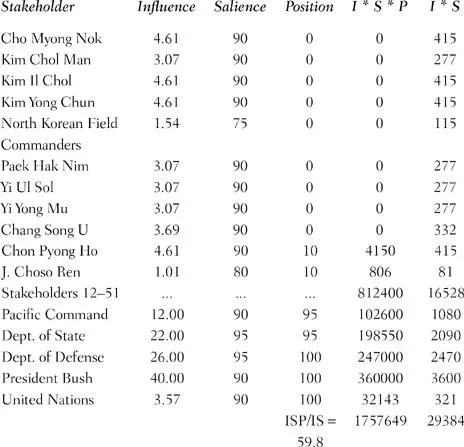

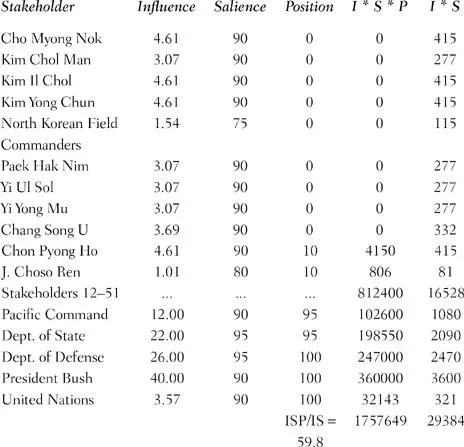

CALCULATION OF THE WEIGHTED MEAN PREDICTION FOR NORTH KOREA

The table below shows detailed data for some of the fifty-six stakeholders in the North Korean nuclear game, and it provides the summary values for influence times salience (that is, power) and also for influence times salience times position for all of the players. The column I × S × P is summed and divided by the sum of the column for I × S. That is, the weighted mean position equals 1,757,649 ÷ 29,384 = 59.8. This number is approximately equal to the position designated as “Slow reduction, U.S. grants diplomatic recognition.”

A SAMPLE OF DATA, WITH THE CALCULATION OF THE WEIGHTED MEAN POSITION

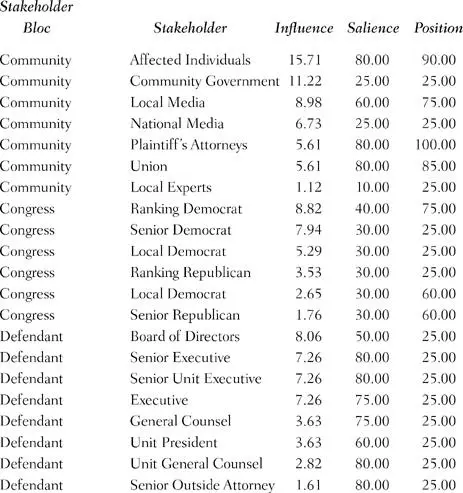

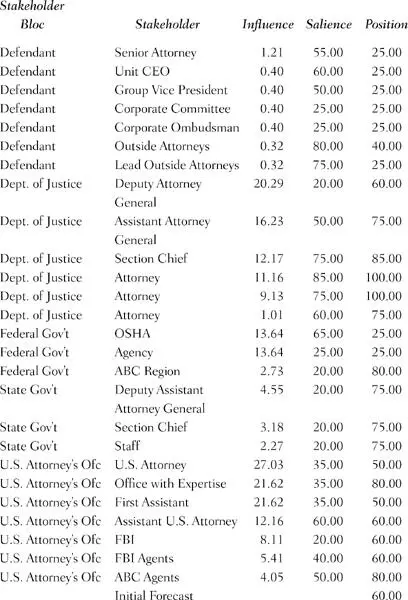

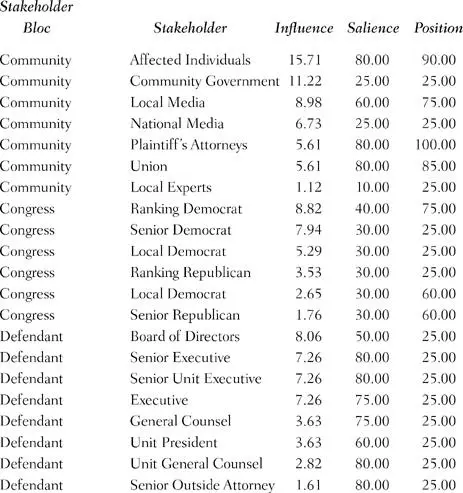

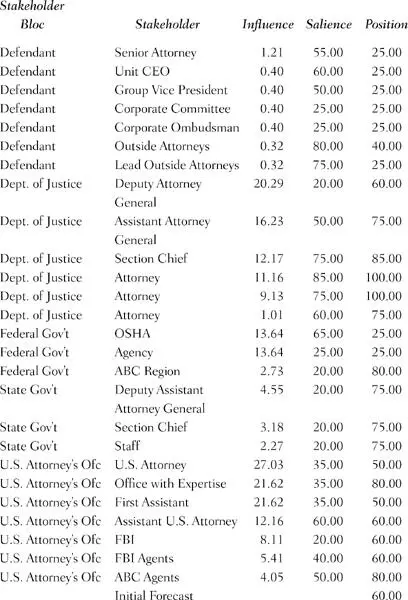

Appendix II

DATA USED TO ENGINEER A COMPLEX LITIGATION

Afterword to the Paperback Edition

Here we are, just about one year since The Predictioneer’s Game first went to press. A lot has been going on in the world since then, giving us a terrific opportunity to look back and see how the forecasting model did. Of course, it will be much more convincing if you go back over the book’s predictions, as well as forecasts I have made online in speeches, podcasts, and so forth, and judge for yourself. There is always the danger that I will unwittingly focus on the best of my predictions and give less credence to those that were wrong, but I will certainly try not to do that. Besides, you can take the model out for a test drive yourself. Just go to www.predictioneersgame.com and click on the game page. You will have the opportunity to use the apprentice version of the model with your own data sets. There’s also a training manual on the game page to help you understand how to build inputs for the model. You won’t get the full output, just the parts intended for prediction rather than engineering, but you should have considerable fun playing with it, and you’ll be able to keep track of your own accuracy as a predictioneer. And if you are a professor teaching a course that can use the model, then you can register for a fuller version online.

Besides being able to play the game yourself, you are going to have the opportunity to understand more about how it works. You’ll get to look under the hood as well as kick the proverbial tires (sorry for all the car talk, but then, I did offer advice on how to buy a car). Some readers are gluttons for punishment. They don’t want to pick up my (admittedly boring) academic publications to find out the nuts and bolts behind my models. They want it here and they want it now. Okay, I’ll provide some of those details as an appendix to this epilogue so that those who really don’t want to look at equations needn’t be bothered and those who do want to look at some math will—hopefully—be satisfied. This just isn’t the place to go into full detail.

Now, back to the predictions and claims of the book. Let’s start with the approach I suggested for buying a car. That’s not strictly derived from the forecasting model, but it is based on the strategic thinking at the heart of game theory. Some readers have tried my method out and reported on their results, and so far all are positive. Paul Daugherty, who happens to be a journalist, was an admitted skeptic. He tried the method and wrote up the results in The Irish Times on October 28, 2009. I’ll let him do the talking:

So, we put it to the test: our goal was to see what sort of discount we could get if we tested the market for a Ford Mondeo 1.8 petrol saloon with around 50,000 miles on the clock, preferably in metallic silver for less than €9,000.

I pitched my wits against the car dealers of Ireland, trying to buy a car the Bruce Bueno de Mesquita way.

Picking out five cars on the Internet that fitted the criteria, I started in Dublin, rang the first dealership on my list and gave the salesperson the following spiel.

“Hello, my name is Paul O’Doherty, I need to buy a car urgently. At noon tomorrow I will walk into a dealership with cash to buy a 2005 Ford Mondeo 1.8 petrol saloon with around 50,000 miles on the clock from the dealer who offers me the best price. You are the first person I’ve rung and I have four others on my list. What’s your best price?” … Lastly I rang a Kildare dealer with an opening price of €6,900. Delivering what I had to say, the best price returned was €6,750 with the final warning that this price wouldn’t be beaten. And, in fairness, it wasn’t.

Читать дальше