Back in December 1997, 175 countries—not including the United States—signed the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto signatories agreed to a benchmark year, 1990, against which to establish targets for greenhouse gas reductions. Greenhouse gas emissions had been rising dramatically in the years between the benchmark and the agreement. The protocols call for a 5.2 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions relative to their levels in 1990. That is about equivalent to saying there should be nearly a 30 percent reduction when compared to the then expected emissions levels in 2010. Some signatories were called upon to make much greater sacrifices than others. For instance, the European Union agreed to reduce its emissions by 8 percent. The United States was asked to reduce its greenhouse gases by 7 percent, Japan by 6 percent, and so forth. A few countries, such as Australia, were given permission to increase their emissions. No restrictions were imposed on developing countries like India and China (or Russia, assigned a 0 percent reduction), although they are now among the world’s largest greenhouse gas polluters. The United States declined to sign on because it objected to the exemption given to rapidly growing economies like China’s and India’s.

Kyoto produced a large market in which polluters and nonpolluters could buy and sell “pollution rights.” This market has helped to rationalize decisions at the level of individual firms, but it alone has so far failed to result in the magnitude of reductions envisioned by the Kyoto Protocol. As we will see shortly, enforcing the 1997 agreement has been virtually impossible.

One consequence of the difficulties encountered since 1997 was a meeting in Bali, Indonesia, in December 2007. The Bali meeting had more modest goals than Kyoto. It represents an interim step on the way to a 2009 deadline by which it is hoped there will be a new international agreement in Copenhagen. After considerable resistance, the U.S. representative at Bali agreed to significant concessions at the last minute. This made it possible to set out the Bali Roadmap for future climate control. Now the question is, will these efforts work?

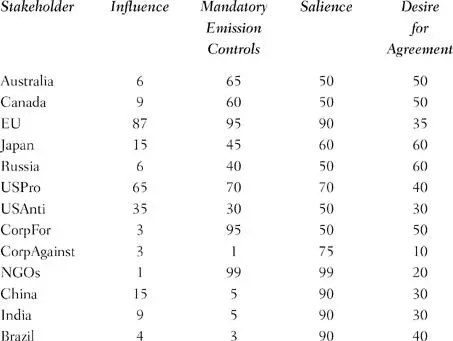

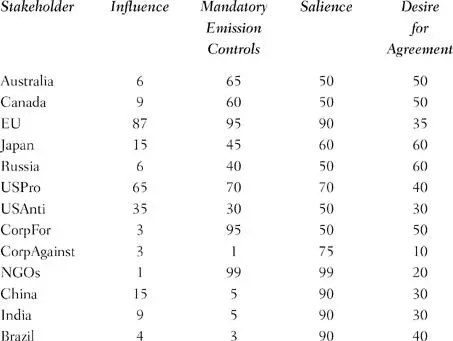

To address the prospects for controlling greenhouse emissions, especially carbon dioxide, let’s start with some data that reflect the views of the big players on global warming. These are the governments and interest groups with the most at stake. In all likelihood, any agreement that can be reached will be settled primarily among these few stakeholders. They include the European Union, the United States—divided between the proportion of American public opinion that favors regulating carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions and those opposed—China, and India. It also includes other relatively large economies such as Russia’s, Japan’s, Canada’s, and Australia’s, plus the growing economy of Brazil. For good measure, I have also represented environmental nongovernmental organizations (labeled here as NGOs), since they had a significant presence at Bali, and pro-environment and less sympathetic multinational corporations. In each case I have estimated potential influence in negotiations over an agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol, position (explained in a moment), salience for mandatory emission controls, and the extent to which the stakeholder is committed to finding an agreement (even if it is not the one they favor) or will stick to their guns under political pressure (holding out for the policy they believe in). This last variable, as you know, is new to the new model I have been developing and testing for a few years. This is the model that I promised earlier I would apply to this case, just as I applied it to forecasts about Pakistan and other crises in the previous chapter

I have rated the players’ positions on a scale from 0 to 100. A position of 50 is equivalent to continuing the greenhouse gas targets that came out of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. These standards, as I previously discussed, called for rollbacks based on 1990 emission levels. Higher values on the position scale reflect tougher standards. For example, 60 is a 10 percent toughening of standards relative to the 1990 benchmark, 100 a 50 percent increase in mandatory greenhouse emissions reductions compared to 1990. Likewise, values below 50 reflect a weakening of the terms contained in the Kyoto agreement.

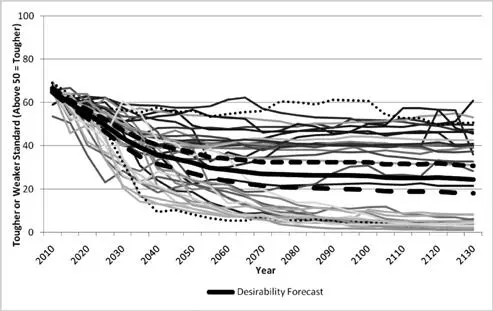

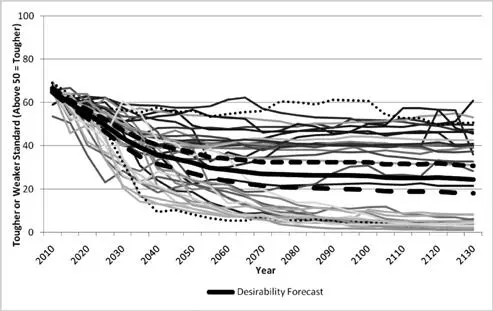

Ten years passed between the Kyoto negotiations and the new round of talks that began in Bali in 2007. There were intermediate discussions in 2000 and 2001, but these were not particularly dramatic. With that in mind, I have viewed the bargaining periods as fairly long, taking exchanges of ideas among the big players about how to deal with global warming as cycling around about once every five years. That means I have simulated the negotiated standards out for about 125 years. That is certainly a long time. We will want to take more seriously the predictions closer in than farther out, since a great deal can happen between now and 2130 (when none of us will be around to check on accuracy or praise success). Because so much can happen, I have simulated the data with random shocks to salience and to each stakeholder’s interest in building consensus or sticking to its guns. By randomly changing 30 percent of the salience values and 30 percent of the flexibility values in each bargaining round, we can look at a range of predicted futures to see whether the global warming simulations reveal strong trends. That will help us sort out how confident we can be about the toughness or weakness of future regulations of greenhouse gas emissions.

First let’s see what the big picture looks like. Then we will examine the simulations in more detail to get a sense of how optimistic or pessimistic we should be.

The heavy solid black line in figure 11.2 shows the most likely emission standard predicted by the game. The two heavy dotted lines depict the range of regulatory values that we can be 95 percent confident includes the true future regulatory environment according to the simulations. That range of values is pretty narrow, encompassing barely five points up or down through about 2050. After that, as we should expect, there is more uncertainty, but even as far into the future as 2130 the range is only about ten points up or down, so these are probably pretty reliable forecasts.

FIG. 11.2. The Withering Will to Regulate Greenhouse Gases

The most likely value—the heavy solid line—reflects our best estimate of what the big players might broadly agree to if the global warming debate continues without any significant new discoveries in its favor or against it. It tells us two stories. First, the rhetoric of the next twenty or thirty years endorses tougher standards than those proposed—and mostly ignored—at Kyoto in 1997. We know this because the predicted value through 2025 is above 50 on the scale. That’s the green part of the story. Second, support for tougher regulations falls almost relentlessly as the world closes in on 2050—a crucial date in the global warming debate. When we get to 2050, the mandatory standard being acted on is well below that set at Kyoto. By about 2070 it is down to 30, representing a significant weakening in standards. By 2100 it is closing in on 20 to 25. There’s no regulatory green light left in the story by its end.

Now let’s probe the details a bit. The figure shows us that there are some considerably more optimistic scenarios and also some considerably more pessimistic views that fall outside the 95 percent confidence interval. The most optimistic and pessimistic scenarios are depicted by the dotted lines at the top and bottom of the figure. The most optimistic scenario predicts no rollback in emission controls. It never dips below 50 on the scale. In fact, most of the time in this scenario the predicted level of greenhouse gas reduction hovers around 60, implying a 10 percent or so tougher standard than was agreed to in Kyoto. The pro-control faction in the United States is the driving force behind this optimistic perspective. Their salience rises from its initial level of 70 and remains remarkably high, hovering around 100. Because the issue becomes so salient to them, this U.S. group’s power (resources multiplied by salience) comes to dominate debate. Although their inclination to be tough might not be enough to satisfy diehard greens, keeping this group (mostly liberal Democrats) highly engaged is the best hope for tougher standards.

Читать дальше