Isaiah Berlin - The Hedgehog and the Fox

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Isaiah Berlin - The Hedgehog and the Fox» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Princeton University Press, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hedgehog and the Fox

- Автор:

- Издательство:Princeton University Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hedgehog and the Fox: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hedgehog and the Fox»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hedgehog and the Fox — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hedgehog and the Fox», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The essay endures, in other words, because it is not simply about Tolstoy – it is about all of us. We can be reconciled to our ‘sense of reality’ 2– accept it for what it is, live life as we find it – or we can hunger for a more fundamental, unitary truth beneath appearance, a truth that will explain or console. 3

Berlin contrasted this longing for unitary truth with a fox’s sense of reality. He was adamant that even a fox’s knowledge could be solid and clear as far as it went. We are not in a fog. We can know, we can learn, we can make moral judgements. Scientific knowledge is clear. What he disputed is that science or reason can give us a final certainty that cuts to the core of reality. Most of us settle for this. Wisdom, he writes, is not surrender to illusion, but rather an acceptance of the ‘unalterable medium in which we act’, ‘the permanent relationships of things’, ‘the universal texture of human life’. 1This we can know, not by science or by reasoning, so much as by a deep coming to terms with what is . Berlin himself, in his final years, achieved this kind of serenity. It seemed to be rooted in the acceptance and reconciliation that imbued his sense of reality. 2

A select few refuse to come to terms with reality. They refuse to submit, and seek – whether through art or science, mathematics or philosophy – to pierce through the many disparate things that foxes know, to a core certainty that explains everything. Karl Marx was such a figure, the most implacable hedgehog of them all.

The grandeur of hedgehogs is that they refuse our limitations. Their tragedy is that they cannot be reconciled to them at the end. Tolstoy was ruthlessly dismissive of every available doctrine of truth, whether religious or secular, yet he could not abandon the conviction that some such ultimate truth could be grasped if only he could overcome his own limitations. ‘Tolstoy’s sense of reality was until the end too devastating to be compatible with any moral ideal which he was able to construct out of the fragments into which his intellect shivered the world.’ 1At the end he was a figure of tragic grandeur – ‘a desperate old man, beyond human aid, wandering self-blinded at Colonus’ 2– unable to be at peace with the irremediable limitations of his own humanity.

This essay asks basic questions of anyone who reads it: What can we know? What does our ‘sense of reality’ tell us? Are we reconciled to the limits of human vision? Or do we long for something more? If so, what certainty can we hope to achieve one day? Because these are enduring questions of human existence, this great essay will last as long as people come seeking answers.

1Available in two of Berlin’s collections: The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays, ed. Henry Hardy and Roger Hausheer (London, 1997), and Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford, 2002).

2Michael Ignatieff, Isaiah Berlin: A Life (London, 1998), 297–8.

179 below.

243, 70, 71, 76, 85, 89, 105 below.

3See also Berlin’s ‘The Sense of Reality’ (the Elizabeth Cutter Morrow Lecture, Smith College, 1953), in his collection of the same title, ed. Henry Hardy (London, 1996).

175–6, 74 below.

2See my ‘Berlin in Autumn’, repr. in Henry Hardy (ed.), The Book of Isaiah: Personal Impressions of Isaiah Berlin (Woodbridge, 2009).

190 below.

2ibid.

EDITOR’S PREFACE

I am very sorry to have called my own book The Hedgehog

and the Fox . I wish I hadn’t now.

Isaiah Berlin 1

THIS SHORT BOOK IS ONE of the best-known and most widely celebrated works by Isaiah Berlin. Its somewhat complicated history is perhaps worth summarising briefly.

The original, shorter, version, based on a lecture delivered in Oxford, was dictated (the author claimed) in two days, and published in a specialist journal in 1951 under the somewhat less memorable title ‘Lev Tolstoy’s Historical Scepticism’. 2Two years later, at George Weidenfeld’s 3inspired suggestion, it was reprinted in a revised and expanded form under its present, famous, title, 4afforced principally by two additional sections on Tolstoy and Maistre, and dedicated to the memory of the author’s late friend Jasper Ridley (1913–43), killed in the Second World War ten years earlier.

Twenty-five years after that, it was included in a collection of Berlin’s essays on nineteenth-century Russian thinkers, of which a second, much revised, edition appeared a further thirty years thereafter. 1It also appeared in the year of Berlin’s death in a one-volume retrospective collection drawn from the whole of his work. 2Numerous translations have been made over the years: work on a French version in the mid-1950s by Aline Halban, 3soon to be Berlin’s wife, was the occasion for regular meetings in the period preceding their marriage. Finally, an excerpted text has been published as Tolstoy and History . 4The free-standing complete text has remained in print ever since it was first published, and now enters the latest phase in its history.

For each of the collections of essays by Berlin that I have edited or co-edited – that is, in 1978, 1997 and 2008 – corrections were made in the text and corrections and additions to the notes. Translations of passages in languages other than English (some of them rather long) were also added. The present edition of the essay includes all these revisions and more besides.

New to this edition are the foreword by Berlin’s biographer Michael Ignatieff, and the appendix, which includes (extracts from) letters Berlin wrote about the essay at the time it was written and published, and later, and also (extracts from) contemporary reviews and later commentary.

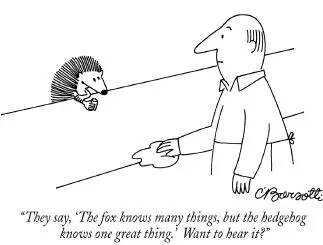

The book was enthusiastically reviewed when it first appeared, and has become a staple of literary criticism. Berlin’s distinction between the monist hedgehog and the pluralist fox, like his celebration of Kant’s ‘crooked timber of humanity’, 1has entered the vocabulary of modern culture. It is invoked so frequently in speech, in print and online that it has developed an untrackable life of its own, inspiring (among much else) a parody by John Bowle in Punch (reproduced in the appendix) and cartoons such as the one by Charles Barsotti reproduced overleaf. 2

Since the new edition has been reset, the pagination differs from that of the various earlier editions. This will cause some inconvenience to readers trying to follow up references to those editions. I have therefore posted a concordance of the editions, compiled by Nick Hall, at ‹http://berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/published_works/hf/concordance.html›, so that references to one edition can readily be converted into references to another.

Page references are mostly given as plain numerals. Cross-references to notes (in this volume, unless otherwise stated) are given in the form ‘123/4’, i.e. ‘page 123, note 4’.

Tribute should be paid to Berlin’s friend Julian Asquith, 3from whom he learned of the fragment that gave the book its title. I am extremely grateful to Aileen Kelly for invaluable help with the text and references during the preparation of the first edition of Russian Thinkers. Thanks in connection with the present edition are also due to Al Bertrand, Ewen Bowie, Quentin Davies (John Bowle’s literary executor, for allowing me to reprint Bowle’s parody), Leofranc Holford-Strevens, Eva Papastratis, John Penney and above all Mary Merry.

Henry Hardy

Heswall, May 2012

1Letter to Morton White, 2 May 1955. This may be sincere, but the intellectual influence of the book has surely been significantly enhanced by its felicitous title.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hedgehog and the Fox»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hedgehog and the Fox» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hedgehog and the Fox» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.