Soap stars seem to do it nightly–Slap and shag and rape each other.If I heard the plot-line rightlyDarren’s pregnant by his brother.News of bombs in Central London,Flesh and blood disintegrate.Teenage voices screaming proudly,‘Allah akbar! God is great!’

Soap stars seem to do it nightly–Slap and shag and rape each other.If I heard the plot-line rightlyDarren’s pregnant by his brother.News of bombs in Central London,Flesh and blood disintegrate.Teenage voices screaming proudly,‘Allah akbar! God is great!’

So, your turn. Relax and feel the force.

IV

Ternary Feet: we meet the anapaest and the dactyl, the molossus, the tribrach, the amphibrach and the amphimacer

Ternary Feet

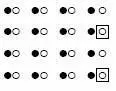

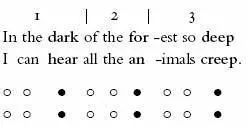

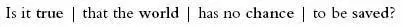

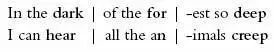

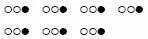

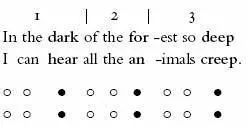

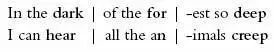

Now that you are familiar with four types of two-syllable, binary (or duple as a musician might say) foot–the iamb , the trochee , the pyrrhic and the spondee –try to work out what is going on metrically in the next line.In the dark of the forest so deepI can hear all the animals creep.

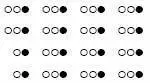

Did you get the feeling that the only way to make sense of this metre is to think of the line as having feet with three elements to them, the third one bearing the beat? A kind of Titty- tum , titty- tum , titty- tum triple rhythm? A ternary foot in metric jargon, a triple measure in music-speak.

Such a  titty- tumfoot is called an anapaest , to rhyme with ‘am a beast’, as if the foot is a skiing champion, Anna Piste. It is a ternary version of the iamb, in that it is a rising foot, going from weak to strong, but by way of two unstressed syllables instead of the iamb’s one.

titty- tumfoot is called an anapaest , to rhyme with ‘am a beast’, as if the foot is a skiing champion, Anna Piste. It is a ternary version of the iamb, in that it is a rising foot, going from weak to strong, but by way of two unstressed syllables instead of the iamb’s one.

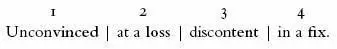

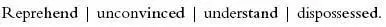

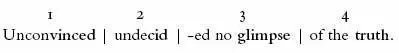

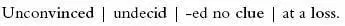

Any purely anapaestic line is either a monometer of three syllables…Uncon vinced

…a dimeter of six…Uncon vinced, at a loss

…a trimeter of nine…Uncon vinced, at a loss, discon tent

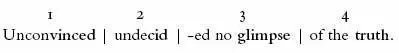

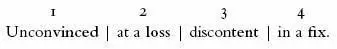

…or a tetrameter of twelve…Uncon vinced, at a loss, discon tent, in a fix.

And so on. Don’t be confused: that line of twelve syllables is not a hexameter, it is a tetrameter . It has four stressed syllables.

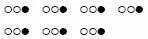

Remember: it is the number of stresses , not the number of syllables , that determines whether it is penta-or tetra-or hexa-or any other kind of -meter:

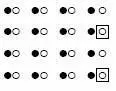

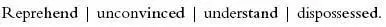

Now look at the anapaestic tetrameter above and note one other thing: the first foot is one word, the second foot is two thirds of a single word, foot number three is two and a third words and the fourth foot three whole words. Employing a metre like the anapaest doesn’t mean every foot of a line has to be composed of an anapaestic word:

That would be ridiculous, as silly as an iambic pentameter made up of ten words, as mocked by Pope–not to mention fiendishly hard. Nor would an anapaestic tetrameter have to be made up of four pure anapaestic phrases :

The rhythm comes through just as clearly with…

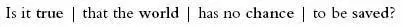

or…

…where every foot has a different number of words. It is the beats that give the rhythm. Who would have thought poetry would be so arithmetical? It isn’t, of course, but prosodic analysis and scansion can be. Not that any of this really matters for our purposes: such calculations are for the academics and students of the future who will be scanning and scrutinising your work.

Poe’s ‘Annabel Lee’ is in anapaestic ballad form (four-stress lines alternating with three-stress lines):

For the moonnever beamswithout bringing me dreamsOf the beautiful Annabel Lee.

For the moonnever beamswithout bringing me dreamsOf the beautiful Annabel Lee.

I suppose the best-known anapaestic poem of all (especially to Americans) is Clement Clarke Moore’s tetrametric ‘The Night Before Christmas’:

’Twas the nightbefore Christmas, when allthrough the houseNot a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;The stockings were hungby the chimney with careIn hopesthat St Nicholas soonwould be there.

’Twas the nightbefore Christmas, when allthrough the houseNot a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;The stockings were hungby the chimney with careIn hopesthat St Nicholas soonwould be there.

The second couplet has had its initial weak syllable docked in each line. This is called a clipped or acephalous (literally ‘headless’) foot. You could just as easily say the anapaest has been substituted for an iamb, it amounts to precisely the same thing.

Both the Poe and the Moore works have a characteristic lilt that begs for the verse to be set to music (which they each have been, of course), but anapaests can be very rhythmic and fast moving too: unsuited perhaps to the generality of contemplative poetry, but wonderful when evoking something like a gallop. Listen to Robert Browning’s ‘How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix’:I sprangto the stirrup and Joris and heI galloped, Dirk galloped, we galloped all three.

It begs to be read out loud. You can really hear the thunder of the hooves here, don’t you think? Notice, though, that Browning also dispenses with the first weak syllable in each line. For the verse to be in ‘true’ anapaestic tetrameters it would have to go something like this (the underline represents an added syllable, not a stress):Then I sprang to the stirrup and Joris and heAnd I galloped, Dirk galloped, we galloped all three.

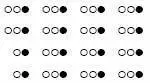

But Browning has given us clipped opening feet:Da- dum, titty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tumDa- dum, titty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tum.

instead of the fullTitty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tumTitty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tum, titty- tum

If you tap out the rhythms of each of the above with your fingers on the table, or just mouth them to yourself (quietly if you’re on a train or in a café, you don’t want to be stared at) I think you will agree that Browning knew what he was about. The straight anapaests are rather dull and predictable. The opening iamb or acephalous foot, Da- dum! makes the whole ride so much more dramatic and realistic, mimicking the way horses hooves fall. Which is not to say that, when well done, pure anapaests can’t work too. Byron’s poem ‘The Destruction of Sennacharib’ shows them at their best.

Читать дальше

Soap stars seem to do it nightly–Slap and shag and rape each other.If I heard the plot-line rightlyDarren’s pregnant by his brother.News of bombs in Central London,Flesh and blood disintegrate.Teenage voices screaming proudly,‘Allah akbar! God is great!’

Soap stars seem to do it nightly–Slap and shag and rape each other.If I heard the plot-line rightlyDarren’s pregnant by his brother.News of bombs in Central London,Flesh and blood disintegrate.Teenage voices screaming proudly,‘Allah akbar! God is great!’

titty- tumfoot is called an anapaest , to rhyme with ‘am a beast’, as if the foot is a skiing champion, Anna Piste. It is a ternary version of the iamb, in that it is a rising foot, going from weak to strong, but by way of two unstressed syllables instead of the iamb’s one.

titty- tumfoot is called an anapaest , to rhyme with ‘am a beast’, as if the foot is a skiing champion, Anna Piste. It is a ternary version of the iamb, in that it is a rising foot, going from weak to strong, but by way of two unstressed syllables instead of the iamb’s one.

For the moonnever beamswithout bringing me dreamsOf the beautiful Annabel Lee.

For the moonnever beamswithout bringing me dreamsOf the beautiful Annabel Lee. ’Twas the nightbefore Christmas, when allthrough the houseNot a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;The stockings were hungby the chimney with careIn hopesthat St Nicholas soonwould be there.

’Twas the nightbefore Christmas, when allthrough the houseNot a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;The stockings were hungby the chimney with careIn hopesthat St Nicholas soonwould be there.