To M’ Colleague

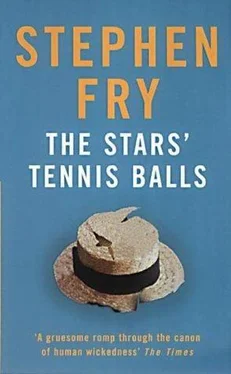

We are merely the stars’ tennis balls, struck and banded

Which way please them

John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi, Act V Scene 3

It all began some time in the last century, in an age when lovers wrote letters to each other sealed up in envelopes. Sometimes they used coloured inks to show their love, or they perfumed their writing-paper with scent.

41 Plough Lane,

Hampstead,

London NW3

Monday, June 2nd 1980

Darling Ned –

I’m sorry about the smell. I hope you ye opened this somewhere private, all on your own. You’ll get teased to distraction otherwise. It’s called Rive Gauche, so I’m feeling like Simone de Beauvoir and I hope you’re feeling like Jean-Paul Sartre. Actually I hope you aren’t because I think he was pretty horrid to her. I’m writing this upstairs after a row with Pete and Hillary. Ha, ha, ha! Pete and Hillary, Pete and Hillary, Pete and Hillary. You hate it when I call them that, don’t you? I love you so much. If you saw my diary you’d die. I wrote a whole two pages this morning. I drew up a list of everything that’s wonderful and glorious about you and one day when we re together for ever I might let you look at it and you’ll die again.

I wrote that you’re old-fashioned.

One: the first time we met you stood up when I entered the room, which was sweet, but it was the Hard Rock Café and I was coming out of the kitchen to take your order.

Two: every time I refer to my mum and dad as Peter and Hillary, you go pink and tighten your lips.

Three: when you first talked to Pete and – all right, I’ll let you off – when you first talked to Mum and Dad, you let them go on and on about private education and private health and how terrible it was and how evil the government is and you never said a word. About your dad being a Tory MP, I mean. You talked beautifully about the weather and incomprehensibly about cricket. But you never let on.

That’s what the row today was about, in fact. Your dad was on Weekend World at lunchtime, you prolly saw him. (I love you, by the way. God, I love you so much.)

‘Where do they find them?’ barked Pete, stabbing a finger at the television. ‘Where do they find them?’

‘Find who?’ I said coldly, gearing up for a fight.

‘Whom,’ said Hillary.

‘These tweed-jacketed throwbacks,’ said Pete.

‘Look at the old fart. What right has he got to talk about the miners? He wouldn’t recognise a lump of coal if it fell into his bowl of Brown Windsor soup.

‘You remember the boy I brought home last week?’ I said, with what I’m pretty sure any observer would call icy calm.

‘Job security he says!’ Peter yelled at the screen. ‘When have you ever had to worry about job security, Mr Eton, Oxford and the Guards?’ Then he turned to me. ‘Hm? What boy? When?’

He always does that when you ask him a question – says something else first, completely off the subject, and then answers your question with one (or more) of his own. Drives me mad. (So do you, darling Neddy. But mad with deepest love.) If you were to say to my father, ‘Pete, what year was the battle of Hastings?’ he'd say, ‘They’re cutting back on unemployment benefit. In real terms it’s gone down by five per cent in just two years. Five per cent. Bastards. Hastings? Why do you want to know? Why Hastings? Hastings was nothing but a clash between warlords and robber barons. The only battle worth knowing about is the battle between…’ and he’d be off. He knows it drives me mad. I think it prolly drives Hillary mad too. Anyway, I persevered.

‘The boy I brought home,’ I said. ‘His name was Ned. You remember him perfectly well. It was his half term. He came into the Hard Rock two weeks ago.

‘The Sloane Ranger in the cricket jumper, what about him?’

‘He is not a Sloane Ranger!’

‘Looked like one to me. Didn’t he look like a Sloane Ranger to you, Hills?’

‘He was certainly very polite,’ Hillary said.

‘Exactly.’ Pete returned to the bloody TV where there was a shot of your dad trying to address a group of Yorkshire miners, which I have to admit was quite funny. ‘Look at that! First time the old fascist has ever been north of Watford in his life, I guarantee you. Except when he’s passing through on his way to Scotland to murder grouse. Unbelievable. Unbelievable.’

‘Never mind Watford, when did you last go north of Hampstead?’ I said. Well, shouted. Which was fair I think, because he was driving me mad and he can be such a hypocrite sometimes.

Hillary went all don’t-you-talk-to-your-father-like-that-ish and then got back to her article. She’s doing a new column now, for Spare Rib, and gets ratty very easily.

‘You seem to have forgotten that I took my doctorate at Sheffield University,’ Pete said, as if that qualified him for the Northerner of the Decade Award.

‘Never mind that,’ I went on. ‘The point is Ned just happens to be that man s son.’ And I pointed at the screen with a very exultant finger. Unfortunately the man on camera just at that moment was the presenter.

Pete turned to me with a look of awe. ‘That boy is Brian Walden’s son?’ he said hoarsely. ‘You’re going out with Brian Walden’s son?’

It seems that Brian Walden, the presenter, used to be a Labour MP. For one moment Pete had this picture of me stepping out with socialist royalty. I could see his brain rapidly trying to calculate the chances of his worming his way into Brian Walden’s confidence (father-in-law to father-in-law) wangling a seat in the next election and progressing triumphantly from the dull grind of the Inner London Education Authority to the thrill and glamour of the House of Commons and national fame. Peter Fendeman, maverick firebrand and hero of the workers, I watched the whole fantasy pass through his greedy eyes. Disgusting.

‘Not him!’ I said. ‘Him!’ Your father had appeared back on screen again, now striding towards the door of Number Ten with papers tucked under his arm.

I love you, Ned. I love you more than the tides love the moon. More than Mickey loves Minnie and Pooh loves honey. I love your big dark eyes and your sweet round bum. I love your mess of hair and your very red lips. They are very red in fact, I bet you didn’t know that. Very few people have lips that really are red in the way that poets write about red. Yours are the reddest red, a redder red than ever I read of, and I want them all over me right now – but oh, no matter how red your lips, how round your bum, how big your eyes, it’s you that I love. When I saw you standing there at Table Sixteen, smiling at me, it was as if you were entirely without a body at all. I had come out of the kitchen in a foul mood and there shining in front of me I saw this soul. This Ned. This you. A naked soul smiling at me like the sun and I knew I would die if I didn’t spend the rest of my life with it.

But still, how I wished this afternoon that your father were a union leader, a teacher in a comprehensive school, the editor of the Morning Star, Brian Walden himself – anything but Charles Maddstone, war hero, retired Brigadier of the Guards, ex colonial administrator. Most of all, how I wish he was anything but a cabinet minister in a Conservative government.

That’s not right though, is it? You wouldn’t be you then, would you?

When Pete and Hillary both got it, they stared from me to the screen and back again. Hillary even looked at the chair you sat in the day you came round. Glared at the thing as if she wanted it disinfected and burned.

Читать дальше