Bruce Barnbaum - The Art of Photography - An Approach to Personal Expression

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bruce Barnbaum - The Art of Photography - An Approach to Personal Expression» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One final technique of composition that is blatantly misused (to the point of abuse!) is the technique of “framing” the photograph. Its misuse can best be explained by example: a distant range of mountains is set in the center of the frame, and along the left edge is a massive, nearby tree trunk, with one branch of the tree hanging in the sky over the mountains. To most people this type of composition is wonderful. To my way of thinking it is atrocious!

Note

The human eye’s three-degree angle of sharp vision makes it easy to overlook the distractions within the frame, away from points of high interest. Beware of that tendency.

Why? Because the dark tree has no tonal, object, or form relationship to anything else in the photograph. If you look at it from a purely compositional point of view, a heavy line or form (the tree) stands at the edge of a lighter form (the mountains), but the two do not interact in any way. True enough, both the tree and the mountains are natural objects, but rarely is there even one other tree in sight that could start to form a compositional relationship. The tree relates no more to the mountains than a lamp post would. Furthermore, there is nothing aesthetically pleasing about cutting off the image with the dark mass of the tree trunk. Unfortunately, this wretched misuse of compositional technique is so widely seen that most people accept it and many even love it. I strongly urge you to avoid it!

Generally, framing is used in an attempt to create an impression of depth and “presence”, yet framing of that type is meaningful only in the scene, not in the photograph. The intent may be good, but the method used to achieve it is inappropriate. It is the perfect example of the difference between merely “seeing” and “photographic seeing”.

Framing a scene can be highly effective if the framing element relates to the scene in terms of object, or tone, or both. A tree along the left edge could relate to a forest of other trees. An abandoned piece of mining machinery seen through the doorway of the mine entrance could be appealing, if not compelling. Examples of effective framing abound. They should be used. But use them when they have compositional integrity with other elements in the frame. Unify the photograph with elements that interact logically, not with objects that disrupt the overall composition.

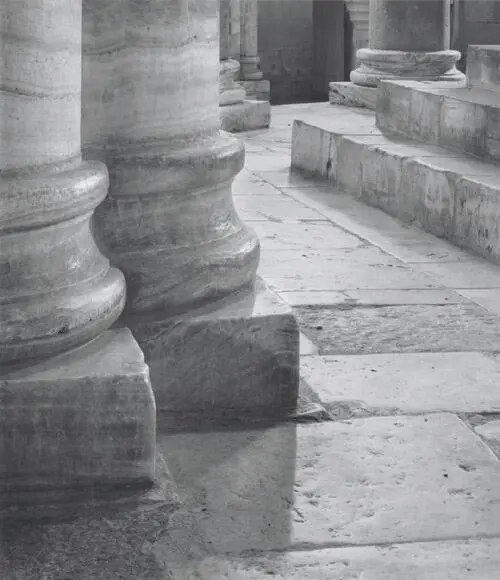

The marble floors, columns, and walls of this small monastery in north-central Italy seemed almost translucent in the midday light. I wanted to concentrate on the overwhelming feeling of light throughout the space, while imparting a feeling of translucency to the marble.

Figure 3-17. Abazio St, Antimo, Italy

Chapter 4. Visualization

THE CONCEPT OF PHOTOGRAPHY as a form of nonverbal communication is a philosophical one. But it’s a very important truth, based on the fact that we all show our pictures to others and we all want to get a response. That alone proves it is indeed a form of communication.

The meaning of composition and its specific elements are theoretical. Both are forerunners of actual photography. They form the foundation for fine photography—and for all visual art—and they must be understood by all creative photographers.

The actual making of a photograph starts with visualization, which is comprised of four steps:

Photographic looking and seeing (two very different things)

Composing an image

Envisioning the final print

Planning a complete strategy to attain the final print

Let’s look at each of these steps in turn and then we’ll look at some alternative approaches.

The Inca understood spectacular landscapes, locating major centers in awesome settings, but none comparable to Machu Picchu. My intent was to highlight the mystical scenery with little more than a reference to the structural remains for context.

Figure 4-1. Machu Picchu in the Mist

Step 1: Photographic Looking and Seeing

Visualization starts with looking and seeing—in-depth looking and seeing, rather than the casual perusal that we all do in our everyday lives. We go about our daily tasks in a routine manner, allowing visual input to slide in and out of our eyes and brain. It is not important to note every detail about a doorway in order to walk through it without smashing your shoulder on the doorjamb. If we stopped to analyze our visual input at all times, we would never accomplish anything. But when we turn to the effort required of photography, our seeing must be much more thorough and intense. In photography, we accomplish nothing unless we analyze everything. We must search for those elements that can be put together to form a photograph.

A corollary to this is that when you look for things to photograph, you start to see everything more intensely. You and your eyes are not just wandering aimlessly, for if you randomly look without carefully inspecting and thinking you see nothing and learn nothing. Photography requires work. The work begins with careful looking, analyzing and thinking. Soon you start to see things in areas you would have overlooked previously. Of course, when you put these “overlooked” items into a photograph, you have to make that photograph compelling enough that the viewer wants to stop to look at it! Let’s face it; if your photograph is as easily overlooked as the items themselves, you’ve accomplished nothing.

You’ll find it important not only to look carefully, but also to draw on your interests to provide deeper, more personal meaning to what you see. I feel that this combination of elements has given me greater appreciation of my surroundings and has led to photographs I may not have made otherwise. My experience is not unique. Yours will probably be similar if you follow your interests.

“Looking” is one thing; “seeing” is quite another. Two people can look at the same thing and one will see a great deal while the other sees nothing. (Of course the person sees something, but finds no meaning .) Just as an experienced detective can inspect a crime scene and find numerous clues that the average person would overlook, so the perceptive photographer can see compositions where others look, but see none. The difference between seeing and not seeing is insight . Insight is the element that separates the detective from the layman, the great photographers from the ordinary ones. Whenever you gain further understanding and insight into the subject matter you’re photographing, you’ll make photographs that progressively penetrate deeper into the essence of that subject. Furthermore, as you gain insight into your own areas of interest (i.e., what excites you, why it excites you, how it excites you), you’ll discover new areas to photograph—perhaps not immediately, but in due time.

Of course, much of this is inevitable. I don’t know a landscape photographer who doesn’t learn about geology, natural history, weather patterns and other things related to the landscape. Portrait photographers gain insight into people and how to work with them more effectively as time goes by. The same is true of photographers in every other specialty. Look at the astounding work of Henri Cartier-Bresson to see how he gained insight into events as they unfolded, developing an uncanny ability to snap the shutter at “the decisive moment”. With increased insight, you’ll be able to analyze a situation more quickly to determine whether it’s worth pursuing and how to best approach it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Art of Photography: An Approach to Personal Expression» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.