Seth Jones - In the Graveyard of Empires - America's War in Afghanistan

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Seth Jones - In the Graveyard of Empires - America's War in Afghanistan» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «In the Graveyard of Empires: America's War in Afghanistan»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a political history of Afghanistan in the “Age of Terror” from 2001 to 2009, exploring the fundamental tragedy of America’s longest war since Vietnam.

After a brief survey of the great empires in Afghanistan—the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the British in the era of Kipling, and the late Soviet Union—Seth G. Jones examines the central question of our own war: how did an insurgency develop? Following the September 11 attacks, the United States successfully overthrew the Taliban regime. It established security throughout the country—killing, capturing, or scattering most of al Qa’ida’s senior operatives—and Afghanistan finally began to emerge from more than two decades of struggle and conflict. But Jones argues that as early as 2001 planning for the Iraq War siphoned off resources and talented personnel, undermining the gains that had been made. After eight years, he says, the United States has managed to push al Qa’ida’s headquarters about one hundred miles across the border into Pakistan, the distance from New York to Philadelphia.

While observing the tense and often adversarial relationship between NATO allies in the Coalition, Jones—who has distinguished himself at RAND and was recently named by

as one of the “Best and Brightest” young policy experts—introduces us to key figures on both sides of the war. Harnessing important new research and integrating thousands of declassified government documents, Jones then analyzes the insurgency from a historical and structural point of view, showing how a rising drug trade, poor security forces, and pervasive corruption undermined the Karzai government, while Americans abandoned a successful strategy, failed to provide the necessary support, and allowed a growing sanctuary for insurgents in Pakistan to catalyze the Taliban resurgence.

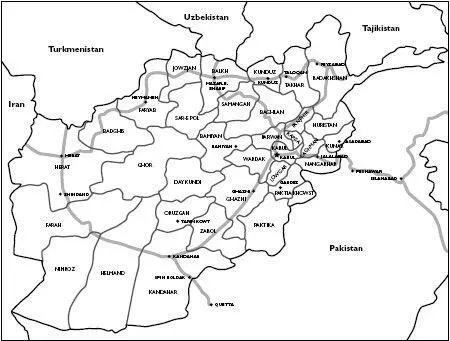

Examining what has worked thus far—and what has not—this serious and important book underscores the challenges we face in stabilizing the country and explains where we went wrong and what we must do if the United States is to avoid the disastrous fate that has befallen many of the great world powers to enter the region. 12 maps and charts

From Publishers Weekly

Since 2001, RAND Corporation political scientist Jones (

) has been observing the reinvigorated insurgency in Afghanistan and weighing the potency of its threat to the country's future and American interests in the region. Jones finds the roots of the re-emergence in the expected areas: the deterioration of security after the ousting of the Taliban regime in 2002, the U.S.'s focus on Iraq as its foreign policy priority and Pakistan's role as a haven for insurgents. He revisits Afghan history, specifically the invasions by the British in the mid- and late-19th century and the Russians in the late-20th to rue how little the U.S. has learned from these two previous wars. He sheds light on why Pakistan—a consistent supporter of the Taliban—continues to be a key player in the region's future. Jones makes important arguments for the inclusion of local leaders, particularly in rural regions, but his diligent panorama of the situation fails to consider whether the war in Afghanistan is already lost.

Review

“A useful and generally lively account of what can go wrong when outsiders venture onto the Afghan landscape.” (

* )

“This is a serious work that should be factored in as a new policy in Afghanistan evolves.” (

* )

“Offers a valuable window onto how officials have understood the military campaign.” (

* )

“[An] excellent book.” (

* )

“How we got to where we are in Afghanistan.” (

* )

“[Zeroes] in on what went awry after America’s successful routing of the Taliban in late 2001.” (

* )

“A blueprint for winning in a region that has historically brought mighty armies to their knees.” (

* )

“Seth Jones . . . has an anthropologist’s feel for a foreign society, a historian’s intuition for long-term trends, and a novelist’s eye for the telling details that illuminate a much larger story. If you read just one book about the Taliban, terrorism, and the United States, this is the place to start.” (

* )

“A timely and important work, without peer in terms of both its scholarship and the author’s intimate knowledge of the country, the insurgency threatening it, and the challenges in defeating it.” (

* )

“A deeply researched and well-analyzed account of the failures of American policies in Afghanistan,

will be mandatory reading for policymakers from Washington to Kabul.” (

* )

“Seth Jones has combined forceful narrative with careful analysis, illustrating the causes of this deteriorating situation, and recommending sensible, feasible steps to reverse the escalating violence.” (

* )

“Seth G. Jones’s book provides a vivid sense of just how paltry and misguided the American effort has been.…

will help to show what might still be done to build something enduring in Afghanistan and finally allow the U.S. to go home.” (

* )

![Ричард Деминг - Whistle Past the Graveyard [= Give the Girl a Gun]](/books/412176/richard-deming-whistle-past-the-graveyard-give-t-thumb.webp)