Nathan Krissoff is one of the 4,229 American service members who gave their lives in Iraq during my presidency. More than 30,000 suffered wounds of war. I will always carry with me the grief their families feel. I will never forget the pride they took in their work, the inspiration they brought to others, and the difference they made in the world. Every American who served in Iraq helped to make our nation safer, gave twenty-five million people the chance to live in freedom, and changed the direction of the Middle East for generations to come. There are things we got wrong in Iraq, but that cause is eternally right.

*To prevent fraud, election officials had each voter dip a finger in purple ink.

**John answered the call to serve four times in my administration—as ambassador to the United Nations, ambassador to Iraq, director of national intelligence, and deputy secretary of state.

***It included J. D. Crouch, Steve’s deputy and a former ambassador to Romania; Meghan O’Sullivan; Bill Luti, a retired Navy captain; Brett McGurk, a former law clerk to Chief Justice William Rehnquist; Peter Feaver, a Duke political science professor who had taken leave to join the administration; and two-star general Kevin Bergner.

****Led by Condi, Ryan Crocker, Brett McGurk, and State Department adviser David Satterfield.

ust before noon on January 20, 2005, I stepped onto the Inaugural platform. From the west front of the Capitol, I looked out on the crowd of four hundred thousand that stretched back across the National Mall. Behind them I could see the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and Arlington National Cemetery on the other side of the Potomac.

ust before noon on January 20, 2005, I stepped onto the Inaugural platform. From the west front of the Capitol, I looked out on the crowd of four hundred thousand that stretched back across the National Mall. Behind them I could see the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and Arlington National Cemetery on the other side of the Potomac.

The 2005 Inauguration marked the third time I had admired that view. In 1989, I was a proud son watching his dad get sworn in. In 2001, I took the presidential oath under freezing rain and the clouds of a disputed election. I had to concentrate on each step down the Capitol stairs, which were a lot narrower than I’d expected. It took time for my senses to adjust to the flurry of sounds and sights. I stared out at the huge huddled mass of black and gray overcoats. I wondered if the sleet would make it hard to see the TelePrompTer when I gave my Inaugural Address.

Four years later, the sky was sunny and clear. The colors seemed more vibrant. And the election results had been decisive. As I walked down the blue-carpeted steps toward the stage, I was able to pick out individual faces in the crowd. I saw Joe and Jan O’Neill, along with a large contingent from Midland. I smiled at the dear friends who had introduced me to the wonderful woman at my side. One thing was for sure: As we enjoyed our burgers that night in 1977, none of us expected this.

I took my seat in the row ahead of Laura, Barbara, and Jenna. Mother and Dad, Laura’s mom, and my brothers and sister sat nearby. Senator Trent Lott, the chairman of the Inaugural Committee, called Chief Justice William Rehnquist to the podium. I stepped forward with Laura, Barbara, and Jenna. Laura held the Bible, which both Dad and I had used to take the oath. It was open to Isaiah 40:31, “But those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

I put my left hand on the Bible and raised my right as the ailing chief justice administered the thirty-five-word oath. When I closed with “So help me God,” the cannons boomed a twenty-one-gun salute. I hugged Laura and the girls, stepped back, and soaked in the moment.

Taking the oath of office for the second time. White House/Susan Sterner

Then it was time for the speech: At this second gathering, our duties are defined not by the words I use, but by the history we have seen together. For a half century, America defended our own freedom by standing watch on distant borders. After the shipwreck of communism came years of relative quiet, years of repose, years of sabbatical—and then there came a day of fire.We have seen our vulnerability—and we have seen its deepest source. For as long as whole regions of the world simmer in resentment and tyranny—prone to ideologies that feed hatred and excuse murder—violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended borders, and raise a mortal threat. There is only one force of history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of human freedom.We are led, by events and common sense, to one conclusion: The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world. … So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

After 9/11, I developed a strategy to protect the country that came to be known as the Bush Doctrine: First, make no distinction between the terrorists and the nations that harbor them—and hold both to account. Second, take the fight to the enemy overseas before they can attack us again here at home. Third, confront threats before they fully materialize. And fourth, advance liberty and hope as an alternative to the enemy’s ideology of repression and fear.

The freedom agenda, as I called the fourth prong, was both idealistic and realistic. It was idealistic in that freedom is a universal gift from Almighty God. It was realistic because freedom is the most practical way to protect our country in the long run. As I said in my Second Inaugural Address, “America’s vital interests and our deepest beliefs are now one.”

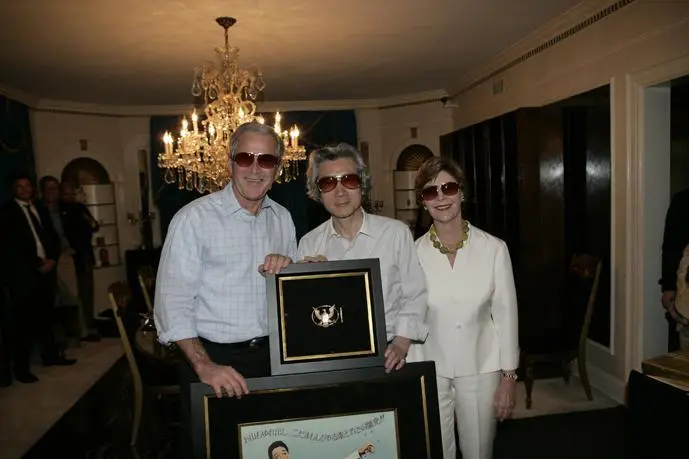

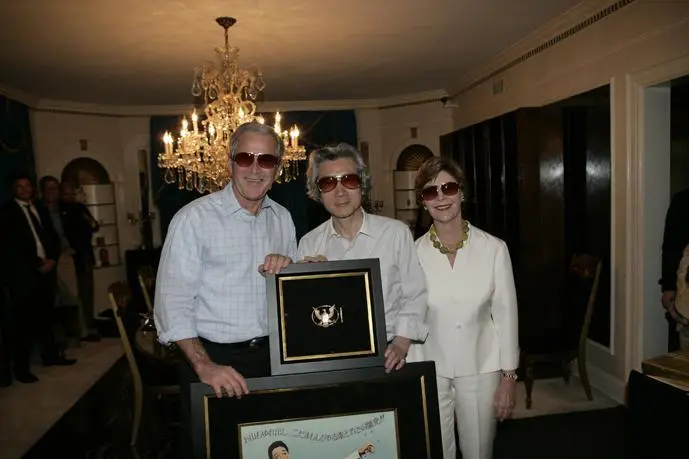

The transformative power of freedom had been proven in places like South Korea, Germany, and Eastern Europe. For me, the most vivid example of freedom’s power was my relationship with Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi of Japan. Koizumi was one of the first world leaders to offer his support after 9/11. How ironic. Sixty years earlier, my father had fought the Japanese as a Navy pilot. Koizumi’s father had served in the government of Imperial Japan. Now their sons were working together to keep the peace. Something big had changed since World War II: By adopting a Japanese-style democracy, an enemy had become an ally.

In addition to helping spread democracy, Junichiro Koizumi was a huge Elvis fan and visited Graceland. White House/Eric Draper

Announcing the freedom agenda was one step. Implementing it was another. In some places, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, we had a unique responsibility to give the people we liberated a chance to build free societies. But these examples were the exception, not the rule. I made clear that the freedom agenda was “not primarily the task of arms.” We would advance freedom by supporting fledgling democratic governments in places like the Palestinian Territories, Lebanon, Georgia, and Ukraine. We would encourage dissidents and democratic reformers suffering under repressive regimes in Iran, Syria, North Korea, and Venezuela. And we would advocate for freedom while maintaining strategic relationships with nations like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Russia, and China.

Читать дальше

ust before noon on January 20, 2005, I stepped onto the Inaugural platform. From the west front of the Capitol, I looked out on the crowd of four hundred thousand that stretched back across the National Mall. Behind them I could see the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and Arlington National Cemetery on the other side of the Potomac.

ust before noon on January 20, 2005, I stepped onto the Inaugural platform. From the west front of the Capitol, I looked out on the crowd of four hundred thousand that stretched back across the National Mall. Behind them I could see the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and Arlington National Cemetery on the other side of the Potomac.