We landed in Baghdad and choppered to Salam Palace, which six years earlier had belonged to Saddam and his brutal regime. As president, I had attended many arrival ceremonies. None was more moving than standing in the courtyard of that liberated palace, next to President Jalal Talabani, watching the flags of the United States and a free Iraq fly side by side as a military band played our national anthems.

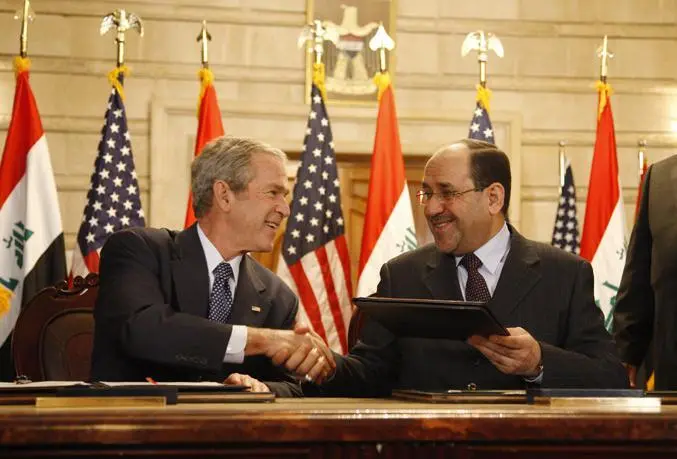

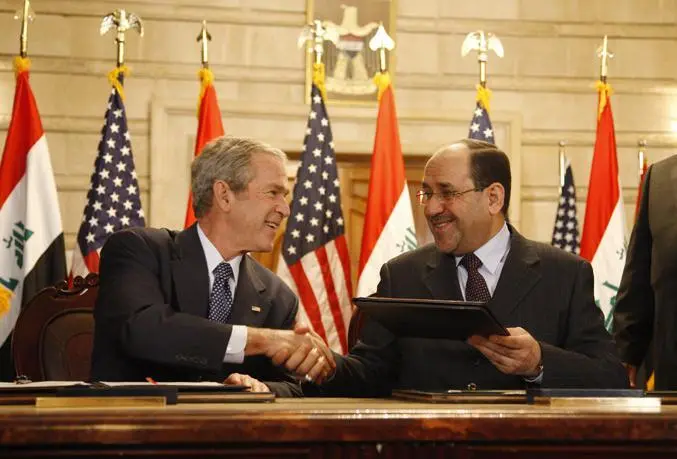

From there we drove to the prime minister’s complex, where Maliki and I signed the SOFA and the SFA and held a final press conference. The room was packed tight, and the audience was closer than at a normal event. A handful of Iraqi journalists sat in front of me on the left. To my right was the traveling press pool and a few reporters based in Iraq. As Maliki called for the first question, a man in the Iraqi press rose abruptly. He let out what sounded like a loud bark, something in Arabic that sure wasn’t a question. Then he wound up and threw something in my direction. What was it? A shoe?

The scene went into slow motion. I felt like Ted Williams, who said he could see the stitching of a baseball on an incoming pitch. The wingtip was helicoptering toward me. I ducked. The guy had a pretty live arm. A split second later, he threw another one. This one was not flying as fast. I flicked my head slightly and it drifted over me. I wish I had caught the damn thing.

I wish I had caught the damn thing. White House/Eric Draper

Chaos erupted. People screamed, and security agents scrambled. I had the same thought I’d had in the Florida classroom on 9/11. I knew my reaction would be broadcast around the world. The bigger the frenzy, the better for the attacker.

I waved off Don White, my lead Secret Service agent. I did not want footage of me being hustled out of the room. I glanced at Maliki, who looked stricken. The Iraqi reporters were humiliated and angry. One man was shaking his head sadly, mouthing apologies. I held up my hands and urged everyone to settle down.

“If you want the facts, it’s a size-ten shoe that he threw,” I said. I hoped that by trivializing the moment, I could keep the shoe thrower from accomplishing his goal of ruining the event.

After the press conference, Maliki and I went to a dinner upstairs with our delegations. He was still shaken and apologized profusely. I took him aside privately with Gamal Helal, our Arabic interpreter, and told him to stop worrying. The prime minister gathered himself and asked to speak before the dinner. He gave an emotional toast about how the shoe thrower did not represent his people, and how grateful his nation was to America. He talked about how we had given them two chances to be free, first by liberating them from Saddam Hussein and again by helping them liberate themselves from the sectarian violence and terrorists.

Having a shoe thrown at me by a journalist ranked as one of my more unusual experiences. But what if someone had said eight years earlier that the president of the United States would be dining in Baghdad with the prime minister of a free Iraq? Nothing—not even flying footwear at a press conference—would have seemed more unlikely than that.

Signing the SOFA and SFA agreements with Nouri al Maliki. White House/Eric Draper

Years from now, historians may look back and see the surge as a forgone conclusion, an inevitable bridge between the years of violence that followed liberation and the democracy that emerged. Nothing about the surge felt inevitable at the time. Public opinion ran strongly against it. Congress tried to block it. The enemy fought relentlessly to break our will.

Yet thanks to the skill and courage of our troops, the new counter-insurgency strategy we adopted, the superb coordination between our civilian and military efforts, and the strong support we provided for Iraq’s political leaders, a war widely written off as a failure has a chance to end in success. By the time I left office, the violence had declined dramatically. Economic and political activity had resumed. Al Qaeda had suffered a significant military and ideological defeat. In March 2010, Iraqis went to the polls again. In a headline unimaginable three years earlier, Newsweek ran a cover story titled “Victory at Last: The Emergence of a Democratic Iraq.”

Iraq still faces challenges, and no one can know with certainty what the fate of the country will be. But we do know this: Because the United States liberated Iraq and then refused to abandon it, the people of that country have a chance to be free. Having come this far, I hope America will continue to support Iraq’s young democracy. If Iraqis request a continued troop presence, we should provide it. A free and peaceful Iraq is in our vital strategic interest. It can be a valuable ally at the heart of the Middle East, a source of stability in the region, and a beacon of hope to political reformers in its neighborhood and around the world. Like the democracies we helped build in Germany, Japan, and South Korea, a free Iraq will make us safer for generations to come.

I have often reflected on whether I should have ordered the surge earlier. For three years, our premise in Iraq was that political progress was the measure of success. The Iraqis hit all their milestones on time. It looked like our strategy was working. Only after the sectarian violence erupted in 2006 did it become clear that more security was needed before political progress could continue. After that, I moved forward with the surge in a way that unified our government. If I had acted sooner it could have created a rift that would have been exploited by war critics in Congress to cut off funding and prevent the surge from succeeding.

From the beginning of the war in Iraq, my conviction was that freedom is universal—and democracy in the Middle East would make the region more peaceful. There were times when that seemed unlikely. But I never lost faith that it was true.

I never lost faith in our troops, either. I was constantly amazed by their willingness to volunteer in the face of danger. In August 2007, I traveled to Reno, Nevada, to speak to the American Legion. Afterward, I met Bill and Christine Krissoff from Truckee, California. Their son, twenty-five-year-old Marine Nathan Krissoff, had given his life in Iraq. His brother, Austin, also a Marine, was at the meeting. Austin and Christine told me how much Nathan loved his job. Then Bill spoke up.

“Mr. President, I’m an orthopedic surgeon,” he said. “I want to join the Navy Medical Corps in Nathan’s honor.”

I was moved and surprised. “How old are you?” I asked.

“I’m sixty, sir,” he replied.

I was sixty-one, so sixty didn’t sound that old to me. I looked at his wife. She nodded. Bill explained that he was willing to retire from his orthopedic practice in California, but he needed a special age waiver to qualify for the Navy.

“I’ll see what I can do,” I said.

When I got back to Washington, I told Pete Pace the story after a morning briefing. Before long, Dr. Krissoff’s waiver came through. He underwent extensive training in battlefield medicine. Shortly after I left office, he deployed to Iraq, where he served alongside Austin and treated wounded Marines.

“I like to think that Austin and I are completing Nate’s unfinished task here in Iraq,” he wrote. “We honor his memory by our work here.” In 2010, I learned that Dr. Krissoff had returned home from Iraq—and then shipped off to Afghanistan.

Читать дальше