A few weeks after the Iraqi government’s offensive in Basra, Petraeus and Crocker returned to Washington to testify in April. This time, there were no antiwar ads in the newspapers and no prolonged battle for funding. NBC News, which in November 2006 had officially pronounced Iraq in a state of civil war, stopped using the term. There was no grand announcement of the retraction.

Calling our gains in Iraq “fragile and reversible,” General Petraeus recommended that we continue withdrawing troops until we hit pre-surge levels, and then pause for further assessment. As Ryan Crocker put it, “In the end, how we leave [Iraq] and what we leave behind will be more important than how we came. Our current course is hard, but it is working. … We need to stay with it.” I agreed.

It was a measure of the surge’s success that one of the biggest military controversies of early 2008 did not involve Iraq. In March, Admiral Fox Fallon—who had succeeded John Abizaid as commander of CENTCOM—gave a magazine interview suggesting he was the only person standing between me and war with Iran. That was ridiculous. I asked Joint Chiefs Chairman Mike Mullen and Vice Chairman Hoss Cartwright what they would do if they were in Fallon’s position. Both said they would resign. Soon after, Fox submitted his resignation. To his credit, he never brought up the issue again. At our last meeting, I thanked him for his service and told him I was proud of his fine career.

I had to find a new commander to lead CENTCOM. There was only one person I wanted: David Petraeus. He had spent three of the past four years in Iraq, and I knew he was hoping to assume the coveted NATO command in Europe. But we needed him at CENTCOM. “If the twenty-two-year-old kids can stay in the fight,” he said, “I can, too.”

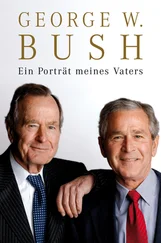

I asked General Petraeus who should replace him in Iraq. Without hesitation, he named his former deputy commander, General Ray Odierno. I first met Ray years earlier when I toured Fort Hood as governor of Texas. Six foot five with a clean-shaven head, the general is an imposing man. He was an early proponent of the surge, and he helped the strategy succeed by positioning the additional troops wisely throughout Baghdad.

For General Odierno, winning in Iraq was more than his duty as a soldier. It was personal. When Ray was home on leave in December 2004, I welcomed his family to the Oval Office, including his son, Lieutenant Anthony Odierno, a West Point graduate who had lost his left arm in Iraq. His father stood silently, beaming with pride, as his son raised his right arm to salute me. Even though Ray had just left for a top position back home at the Pentagon, he accepted the call to return as commander in Baghdad.

With Ray Odierno. White House/Eric Draper

It gave me solace to know that the next president would be able to rely on the advice of these two wise, battle-tested generals. In our own way, we had continued one of the great traditions of American history. Lincoln discovered Generals Grant and Sherman. Roosevelt had Eisenhower and Bradley. I found David Petraeus and Ray Odierno.

By the time the surge ended in the summer of 2008, violence in Iraq had dropped to the lowest level since the first year of the war. The sectarian killing that had almost ripped the country apart in 2006 was down more than 95 percent. Prime Minister Maliki, once the object of near-universal blame and scorn, had emerged as a confident leader. Al Qaeda in Iraq had been severely weakened and marginalized. Iran’s malign influence had been reduced. Iraqi forces were preparing to take responsibility for security in a majority of provinces. American deaths, which routinely hit one hundred a month in the worst stretch of the war, never again topped twenty-five, and dropped to single digits by the end of my presidency. Nevertheless, every death was a painful reminder of the costs of war.

My last major goal was to put Iraq policy onto a stable footing for my successors. In late 2007, we started work on two agreements. One, called a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), laid the legal predicate for keeping American troops in Iraq after the United Nations mandate expired at the end of 2008. The other, called a Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA), pledged long-term diplomatic, economic, and security cooperation between our countries.

Hammering out the agreements took months. Maliki had to deal with serious opposition from factions of his government, especially those with suspected ties to Iran. In the middle of a presidential campaign, Democratic candidates denounced the SOFA as a scheme to keep our troops in Iraq forever. The CIA doubted that Maliki would sign the agreement. I asked the prime minister about it directly. He assured me he wanted the SOFA. He had kept his word in the past, and I believed he would again.

Maliki proved a tough negotiator. He would obtain a concession from our side**** and then come back asking for more. On one level, the endless horse trading was frustrating. But on another level, I was inspired to see the Iraqis conducting themselves like representatives of a sovereign democracy.

As time passed without agreement, I started to get anxious. In one of our weekly videoconferences, I said, “Mr. Prime Minister, I only have a few months left in office. I need to know whether you want these agreements. If not, I have better things to do.” I could tell he was a little taken aback. This was my signal that it was time to stop asking for more. “We will finish these agreements,” he said. “You have my word.”

By November, the agreements were almost done. The final contentious issue was what the SOFA would say about America’s withdrawal from Iraq. Maliki told us it would help him if the agreement included a promise to pull out our troops by a certain date. Our negotiators settled on a commitment to withdraw our forces by the end of 2011.

For years, I had refused to set an arbitrary timetable for leaving Iraq. I was still hesitant to commit to a date, but this was not arbitrary. The agreement had been negotiated between two sovereign governments, and it had the blessing of Generals Petraeus and Odierno, who would oversee its implementation. If conditions changed and Iraqis requested a continued American presence, we could amend the SOFA and keep troops in the country.

Maliki’s political instincts proved wise. The SOFA and SFA, initially seen as documents focused on our staying in Iraq, ended up being viewed as agreements paving the way for our departure. The blowback we initially feared from Capitol Hill and the Iraqi parliament never materialized. As I write in 2010, the SOFA continues to guide our presence in Iraq.

On December 13, 2008, I boarded Air Force One for my fourth trip to Iraq, where I would sign the SOFA and SFA with Prime Minister Maliki. On the flight over, I thought about my previous trips to the country. They traced the arc of the war. There was the joy of the first visit on Thanksgiving Day 2003, which came months after liberation and a few weeks before the capture of Saddam. There was the uncertainty of the trip to meet Maliki in June 2006, when sectarian violence was rising and our strategy was failing. There was the cautious optimism of Anbar in September 2007, when the surge appeared to be working but still faced serious opposition. Now there was this final journey. Even though much of America seemed to have tuned out the war, our troops and the Iraqis had created the prospect of lasting success.

Читать дальше