“It’s roughly half the food, man,” said Curtis.

Chad appeared behind him, nodding.

“We’re still good,” Andrew said. “Half is plenty.” What he didn’t tell them was we’d pillaged the remaining food from Shotsky’s pack and carried it with us. It would be a morbid thing to explain, but we would if it needed to be done.

“Tell ‘im what you told us,” Hollinger said. He was looking straight at Petras. But before Petras could answer, Hollinger turned to Andrew and said, “He told us all about this sacred land we’re crossing. You can call me superstitious, but I don’t just leave behind half my food.”

“You’re making a bigger deal out of this than you need to,” Andrew said calmly. “Like I said, we’ve got enough food. We could survive up here for two months if we had to.”

“You’re wrong and you’re blind,” Hollinger said. “This is bad luck, and it’ll only get worse. You’ll see. You don’t fuck around with the spectral.”

“No such thing as luck.” Andrew dropped his pack off his shoulders, then knelt while he dug around inside. “We’re all responsible for our own achievements and our own mistakes. Luck is just a convenient ideology to place our own blame.”

Though I didn’t necessarily believe in luck, either, I couldn’t help but summon the image of Donald Shotsky, dead of a heart attack and frozen on the ground.

“We spent six months together in the outback, Mike, living off the land. Luck didn’t land our arrows into the chests of our prey so we could eat. That was our own patience and skill. Just like luck didn’t make that one chippie fall in love with you. It was your own confidence that did that—a confidence that’s curiously left you for the time being.”

Hollinger looked like he wanted to respond. In the end, however, he simply crawled over to his gear and reclined near the heat of the fire. Above us, the overhanging cliffs blotted out most of the sky and had kept much of the snow away from the campsite. The ground was fairly dry and warm and covered in small rocks. Hollinger gathered a handful of these rocks and began absently chucking them into the fire.

I looked over at Andrew. He was seated on the ground scrutinizing a map. He looked up and caught my eye. Surprising me, he winked.

I turned away and stretched my sore legs out by the fire. Chad brought me over a steaming cup of tea. “Thanks,” I said, surprised by the gesture.

“No sweat.” He sat beside me. “Everything went cool with old Donald?”

“Fine,” I muttered, covering my mouth with the rim of the cup.

“You think I can get a quick swig of whatever booze you’ve been hoarding?”

“The hell are you talking about?”

“Come on, man. I’ve been watching you, Shakes, been watching the peaks and valleys. I’m just asking for a drop.”

“I’ve got nothing,” I lied, taking a large gulp of the tea and burning the roof of my mouth in the process.

“Bullshit,” Chad said. There was no real anger to his tone. “Anyway, I’m just bitter because I can’t find my other joint.”

“You had two of those monsters?”

“Three.” He grinned like a fiend, his face red in the firelight. “We had a bit of a party last night while you three were gone.”

A bit of a party, I thought, while Donald Shotsky keeled over dead of a heart attack just one hour from base camp. A party while we looted his backpack and left him to freeze to the ground.

But it wasn’t Chad’s fault. I couldn’t be angry, and I didn’t want the disgust on my face to be too apparent. I finished the tea and handed him back the empty cup, thanking him under my breath. Ten minutes later, I curled up and went to sleep, while the bonfire popped and Chad blew sad notes on his harmonica.

Chapter 12

1

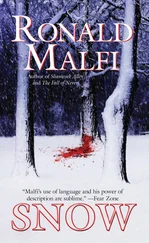

STRADDLING A MONOLITHIC PLATFORM Of ICE-

covered rock, I paused to survey the world below. The vastness of the drop was enough to cause my heart to slam against the walls of my chest, the proximity of the edge—mere inches from my steel-toed boots—both exhilarating and vertiginous. I leaned over the edge, and the mountainside vanished into indistinguishable levels of snow-covered peaks.

My stomach, which in the past twenty-four hours had processed nothing more substantial than a 3 Musketeers bar, ramen noodles, steamed rice, and countless cups of black coffee, seemed to grow heavy and felt as though it wanted to descend deeper into my naval. I hadn’t slept in two days.

We were a full two weeks into the climb, having just crossed the southern pinnacle of the Godesh Ridge, and it was just over a week since I had carved Donald Shotsky’s name in the mountainside where his body had given out. The beginning of the second week had been punctuated by tedious treks through deepening snow and the careful negotiation of serrated, ice-encrusted peaks. The second half of the week had presented a dramatic notch in the south face of themountain, which we climbed vertically while harnessed together in two groups of threes—Petras, Chad, and myself the first of the two groups to ascend. We’d climbed to the summit and continued up the accompanying face as if we were climbing straight to heaven.

Petras passed behind me, peering over my shoulder. His hand on my shoulder was like an anchor.

“Some view,” I said.

“Let’s keep moving.”

Around the other side of the platform, the mountain abruptly ended. Something like three hundred feet below us ran a narrow, snow-packed pass across the shelf of a glacier. Andrew was poised at the lip of the ridge, overlooking the valley. Beside him, Curtis canvassed the surface of the glacier with a pair of binoculars.

I could see the sun streaking colors along the surrounding mountains and the reflection of sunlight mirroring on the ice. Farther down the pass was the hint of a crevasse—a barely noticeable depression in the otherwise undisturbed snow—which I estimated to be at least twenty yards across, though it was impossible to tell for sure from our vantage.

“You guys see it?” Curtis pointed to what appeared to be the beginning of the snow-hidden chasm that ran beneath a buttress of blue stone. “Can’t tell how wide it is, but you can bet your ass it’s deep.”

“Teams,” Andrew said.

I zipped my coat to my chin and rubbed my gloved hands together. Petras bumped his shoulder against mine, and I thought my teeth would shatter in my skull. I attached myself to a fixed rope, while Petras and Chad fed a communal safety line down the face of the cliff. Flexing my fingers, I turned around at the edge of the cliff and gripped the line in both hands.

Petras nodded. “Go.”

I pitched over the side and rappelled down, my feet pushing off the cliff face as I descended. Glancing over my shoulder, I could seebeyond the crevasse and down the far slope of the glacier where, like a grid of blocks, crumbling seracs the size of automobiles rose from the glacier’s surface and cast bluish shadows along the snow.

When I touched down on the glacier, the snow was hard like ice. I tugged at the rope and waved to Petras, who looked down at me.

Once they’d all managed to descend, we trekked across the glacier, heedful of traps or snow bridges bent on deceiving us, until we paused approximately fifteen feet from the edge of the crevasse. This close, it looked wider than I’d originally thought. Forty, maybe fifty feet across. Chad stepped too close to the edge, and Curtis, who was standing beside me rubbing his neck, sucked in air through his clenched teeth.

“Careful,” Petras called to him.

Chad raised a gloved hand in response but didn’t turn. He kept walking until he reached the edge.

“Fucking idiot don’t even have a line tied to him.” Curtis flipped up the collar of his parka. “Think he would have learned his lesson back at base camp.”

Читать дальше