Andrew held his lantern up to the ceiling, which was very near the tops of our heads. “This’ll do. Nice work.”

I was exhausted. Setting my lantern down, I pitched myself against the wall and pulled off my boots. My toes felt like loose marbles rolling around in the tips of my socks.

“You’re not going to believe this,” Andrew said, setting his own lantern down, “but I’ve gotta take a massive shit.” He chuckled to himself. The lantern threw his enormous and hulking shadow against the wall, curling up and splaying it across the undulated ceiling.

I looked past him at the vertical sliver of darkness that defined the narrow passage through which we’d entered.

“What is it?” he said. “Shotsky?”

“I don’t feel good about leaving him out there.”

“Well, we’re certainly not dragging him in here.”

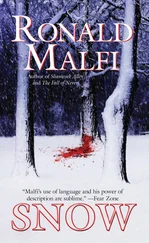

“And now it’s snowing.”

“It’s not a heavy snowfall. Besides, you put out the flags.”

“It just doesn’t seem right.”

Andrew crouched against the wall opposite me. Half his face burned bright yellow in the light of the electric lantern; the other half was masked in shadows. He looked like the embodiment of good and evil. “You blame me for this, don’t you?”

I didn’t answer.

Andrew sighed and shucked off his boots. The cave was so small

I could smell his feet as if they were propped right under my nose. “Funny,” he said and let the word hang in the air.

“What’s that?” My tone was dry, disinterested.

“Funny how he was so quick to throw in the towel. You know, he woke me up in the middle of the night and said he didn’t want to be a burden on the rest of you guys. That he knew he wouldn’t be able to cut it and he had to quit.”

I turned away from him, locking my stare on that vertical sliver of moonlight coming through the rock.

“He would have walked over hot coals to get that twenty grand,” Andrew went on, “and yet he surrendered out of nowhere, as if the money suddenly didn’t matter to him.” He shrugged. “Funny, that’s all.”

“Funny?” I said, still refusing to look at him.

“You don’t think it’s a bit strange?”

“If you’re accusing me of something, spit it out.”

Andrew leaned his head back against the cave, his whole face swallowed by shadows. “We used to be such good friends. Remember?”

“You were Hannah’s friend. I just found you interesting.”

“And now?”

“Now what?”

“You don’t find me interesting anymore?”

I paused to consider my thoughts. “I guess I find you tedious. Maybe it was that tedium I originally found interesting, but now—”

“Now it’s just tedious,” Andrew finished, and I didn’t have to see his face to know he was smiling. “Tell me again what you were doing alone in that cave. We’ve gone through this before, but I don’t think we’ve actually addressed the issue.”

“This,” I suggested, “is a perfect example of tedium.”

This time Andrew laughed—a low, resonant rumbling that played off the closed-in walls. “Come on. Give it up.”

“There’s nothing to tell.”

“Sure there is.” Andrew began slowly and methodically cuffinghis pants up to his knees. “It’s no different than the guy who walks into a doctor’s office and is told he’s got one month of dehumanizing, agonizing life left in him, that some virulent disease is ravaging and liquefying his insides. He’ll be bedridden and lying in his own shit within the week.” He finished cuffing his pants. “No different from that guy leaving the doctor’s office and walking right out into traffic.”

This sent a cold shiver down my spine. Andrew’s words hit too close to home. “Go to hell.”

“I wonder how it would have played out,” Andrew said, “if you hadn’t told old Shotsky about our little behind-the-scenes pact.”

My face burned. My fingernails dug into the rock. “What the hell did Hannah ever see in you?”

“Who knows? Maybe she was a fan of tedium.” He jerked a thumb at the electric lantern. “Mind if I kill this? I wanna get some sleep.”

5

IN THE MORNING. SHOTSKY’S BODY WAS DUSTED

in snow. His eyes were hard, sightless pellets, and I silently cursed myself for not thinking to close his eyelids before the snow came. Andrew had folded his hands atop his chest; they had blued overnight, hardened with frost, their fingers like solid links of metal. Only the orange canvas of his pack, propped beside him like a grave marker, stood out against the earthen colors of his wet clothes and whitish skin. The blue flags I’d pegged at various points in proximity to his body flapped in the wind.

Andrew and I did not speak for most of the hike up the pass. We maintained a considerable distance between us, choosing to hike in solitude than in each other’s company. At one point midway through the climb, I passed Andrew as he sat on his pack in the snow, eating some Cheerios. He did not bother to look in my direction, and I moved past him as if he were invisible.

Come dusk, as I paused to eat my own freeze-dried meal, I couldsee Andrew coming up the pass in pursuit. He walked with the slow, dilatory ease of someone walking through a dream. The setting sun cast soft pastels across the hardened crust of snow, making it glow with patches of purples and pinks, oranges and yellows. Beyond Andrew and farther down the pass, I thought I saw a second figure.

At first, I thought it was a trick of the fading light. But as I watched, I could tell it was a man, moving alongside the walls of the pass as if to keep out of sight. I dropped my pack and scrounged for my binoculars, but by the time I located them and glassed the area, the man had disappeared. I decided it was a trick of the light after all.

Andrew approached, and we crossed down the other side of the pass together, still in silence. However, as we climbed the next ridge and the bonfire became visible, Andrew grabbed one of the loops on my pack and brought me to a halt.

“We shouldn’t tell them about Shotsky,” he suggested. “It’ll crush their spirits. Let’s say we got him back to base camp and everything was fine.”

I hated to agree with him, but he had a point. There was no need to tell the others until after we’d finished. We could even hold a memorial service for Shotsky in the village, if anyone desired it. So I agreed with Andrew, then walked ahead of him toward camp.

I didn’t think it would be a big deal lying about Shotsky until Petras asked how things went.

“Fine,” I muttered, unable to look the bigger man in the eye. “He’s back at camp.” But all I could picture was the way his eyes had frozen open and the orange canvas of his pack standing up through the snowdrift.

“We’ve got a problem,” Hollinger said as Andrew approached camp and set his gear down. “It was either a miscalculation back in the village or we’ve mixed up our bluey with the Sherpas in the valley—”

“Wasn’t no goddamn mix-up,” Curtis chided.

“What happened?” Andrew asked.

“The food,” said Hollinger. “Half the lousy freeze-drieds, the foodstuffs. We’re missing half our tucker.”

I gaped at him. “The food?”

“Half of it’s gone missing, mate.”

“We must have left some behind in the valley without realizing it,” said Petras.

“Pig’s arse!” barked Hollinger.

“Then what else happened to it?” Curtis intervened, his gaze volleying between Michael Hollinger and John Petras. “It was a stupid mistake on our parts, not packing up more carefully in the valley.”

Hollinger threw his hands up. “Bah!”

“Is it really that bad?” Andrew asked, his voice steady.

Читать дальше