“Ah.” Micky made the soothing noise sarcastically. “What we’re going to do, Nick, is screw the bastard.” He glanced at me as I twisted awkwardly to look through the back window. “You think we’re being followed?”

“No.” Instead I had been looking for Angela’s Porsche. She had gone to meet Bannister at Heathrow and, if they left directly for Devon, they could well overtake us on the road. I did not want to see them together. I was jealous. I’d just spent a weekend of gentle happiness with a small sailing boat and with Angela to myself. She had not even been sea-sick. But now, with the horrid crunch of a boat going aground, the real world was impinging on me.

Micky lit a cigarette. “You are bleeding nervous, mate, that’s what you are. I could do a story on that. VC revealed as a wimp.”

“I’m not used to this sort of thing.”

“Which is why you called in the reinforcements?”

“Exactly.”

The ‘reinforcements’ were waiting for us at a service area where the cafeteria offered an all-day breakfast and where Terry Farebrother was mopping up the remains of fried egg and brown sauce with a piece of white bread. I’ve never known a man eat so much as Sergeant Terry Farebrother; he wasn’t so much a human being as a cholesterol processor. Morning, noon and night he ate, and he never seemed to put an inch of fat on his stocky, hard body.

The one thing he’d hated about the Falklands was the uncertainty of meal times and I’d once watched him pick his way into an Argentinian minefield to salvage an enemy pack on the off chance that it might have contained a tin of corned beef. His moustached face was impassive as the two of us approached his table. “Bloody hell,” he greeted Micky Harding. “It’s the Mouse.”

The Mouse, who had known the Yorkshire sergeant in the Falklands, shook Terry’s hand. “You don’t improve with time, do you?”

“I’m just waiting till the Army takes over this country, Mouse, then I’m going to Fleet Street to beat up all the fucking fairies.”

“Not a chance,” Micky said. “We’ve got dolly-bird secretaries who’d crucify you pansies.”

Insults thus dutifully exchanged, Terry nodded a greeting to me and wondered aloud whether there was time to eat another plate of fried grease, but I said we should be moving on. “Shall I buy you a cheese sandwich?” I asked.

“Cheese gives me the wind something rotten. I’ll have a couple of bacon ones instead.” He half crushed my fingers with his handshake. “You’re looking better, boss. Sally said you looked like something the cat threw up.”

“How is Sally?”

“Same as ever, boss, same as ever. Bloody horrible.” Terry was in his civvies; a threadbare blue suit that was buttoned tight round his chest. He’d probably bought the suit the year before he entered the Army as a junior soldier and had never replaced it. He did not really need to, for Terry was one of those men who only look at home in camouflage or battledress. He was a bullock of a man; short, stubborn and utterly dependable. It was good to see him again. “No trouble,” he said when I asked if he’d had difficulties in getting away from the battalion. “They owed me leave after the bleeding exercise.”

“How was the exercise?”

“Same as ever, boss; a bloody cock-up. Got fucking soaked in a turnip field and then half sodding drowned in a river. And, of course, none of the bleeding officers knew where we were or what we were bloody doing. I tell you, mate”—this was to Micky—“if the Russkies ever do come, they’ll fuck through us like a red hot poker going up a pullet’s arse.”

“It’s not surprising, is it?” Micky asked, “when most of our soldiers are as delicate and fastidious as your good self?”

“There is that,” Terry laughed. “So what are we doing?”

“Nick’s nervous,” Micky said dismissively as we walked to the car.

I told Terry that I was indeed nervous, that I was meeting this American girl, and it was just possible, but extremely unlikely, that she might threaten my boat if I didn’t agree to do whatever she wanted, and so I would appreciate it if Terry sat on Sycorax until Micky and I got back to the river.

“Nothing’s going to happen.” Micky accelerated back on to the motorway. “You just get to sit on a bloody boat while it gets dark outside.”

Terry, eating the first of his cold bacon sandwiches, ignored Micky.

“So what will these buggers do? If they do anything?”

“Fire,” I said. Jill-Beth had hinted at arson, and it frightened me.

A hank of rags, soaked in petrol and tossed into the cockpit, would reduce Sycorax to floating ash in minutes. If I turned Jill-Beth’s pro-posal down, which I planned to do, Sycorax would be vulnerable, and never more so than in the hour it would take me to get back from our rendezvous to the river. That fear presupposed that Jill-Beth had already stationed men near the river; men whom she could alert by telephone. The whole scheme seemed very elaborate and fanciful now, but the fear had seemed very real as I had brooded on it during the weekend. Yassir Kassouli was a determined man, and a bitter one, and the fate of one small boat on a Devon river would be nothing to such a man. The fear had prompted me to phone the Sergeants’ Mess from the public phone in the Norfolk village. I’d left a message and Terry had phoned back an hour later. I’d told Angela I’d been talking to Jimmy Nicholls about anchor chains and, though I had hated telling her lies, they seemed preferable to explaining the complicated truth. Now, with Terry’s comforting solidity on my side, I wondered if I had over-reacted. “I don’t think anything will happen, Terry,” I confessed, “but I’m a bit nervous.”

“End of problem, boss. I’m here.” Terry slumped in the back seat and unwrapped another sandwich.

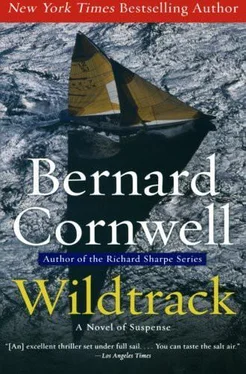

We reached the river two hours later and, as Micky waited on the road above Bannister’s house, I took Terry down through the woods and behind the boathouse to Sycorax . I saw two of Mulder’s crewmen preparing Wildtrack II in the boathouse, ready for tomorrow’s outing when she would be the camera platform for Sycorax ’s maiden trip. I assumed, from their presence, that Mulder must have returned from his victorious Mediterranean foray, but I did not ask. I looked up at the house, but could see no one moving in the windows. I thought of Bannister sleeping with Angela tonight and an excruciating bite of jealousy gnawed at me.

The tide was low. Terry and I climbed down to Sycorax ’s deck and I unlocked the cabin. I did not tell him about the hidden Colt, for I didn’t want his career ruined by an unlicensed firearm’s charge.

“Any food, boss?” he asked hopefully.

“There’s some digestive biscuits in the drawer by the sink, apples in the upper locker and beer under the port bunk.”

“Bloody hell.” He looked disgusted at the choice of food.

“And you might need these.” I dropped the two fire-extinguishers on the newly built chart table. Sycorax might lack a radio, pump, anchors, log, chronometer, compass, loo and a barometer, but I’d taken good care to buy fire-extinguishers. She was a wooden boat and her greatest enemy was not the sea but fire. “And if anyone asks you what you’re doing here, Terry, tell them you’re a mate of mine.”

“I’ll tell them to fuck off, boss.”

“I should be back by nine,” I said, “and we’ll go over the river for a pint.”

“And a baby’s head?” he asked hopefully.

“They do a very good steak and kidney pudding,” I confirmed.

If there was one certainty about this evening now, it was that Sycorax was safe. Kassouli would need an Exocet to take out Terry Farebrother, and even then I wasn’t sure the Exocet would win.

Читать дальше