She smiled back. “Does that mean you’re going to help us, Nick?” I was hopeless at telling lies, and did not think that an outright statement of compliance would be convincing. I shrugged, then began pacing beneath the trees as I spoke. “I don’t know, Jill-Beth.

I just don’t share your conviction that Bannister’s guilty. That worries me. I don’t like him, but I’m not sure that’s sufficient grounds for ruining his chances of the St Pierre.” I was making noises to cover my nervousness, then I realized that by pacing up and down I was constantly turning the microphone away from Jill-Beth. Not that she was saying much, except the odd acknowledgement, but I stopped and faced her.

She sighed, as though exasperated by my havering. “All you have to do, Nick, is sail on Bannister’s boat. You agree to do that, and you get one hundred thousand dollars now, and another three hundred thousand when it’s over.”

“I’ve already told him I won’t sail,” I said, as though it was an insuperable barrier to her ambitions.

She shrugged. “Would he believe you if you changed your mind?” It was very silent under the trees; the wind was muffled and the dead needles acted as insulation. It made our voices seem unnaturally loud.

“He’d believe me,” I said reluctantly.

“So tell him.”

“And if I don’t do it—” I was trying not to make my voice stilted, even though I was stating the obvious “—Kassouli will pull all his jobs out of Britain?”

She smiled. “You’ve got it. But not just his jobs, Nick. He’ll pull out his investments, and he’ll move his operations to the Continent.

And a slew of British firms can kiss their hopes of new contracts on American projects goodbye. It’ll be tough, Nick, but you’ve met him.

He’s a determined guy. Kassouli doesn’t care if he goes down for a few millions, he can spare them.”

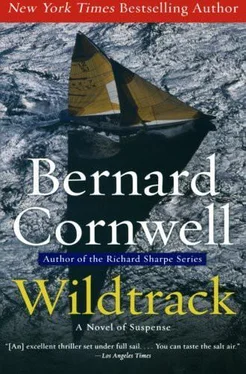

I paused. It seemed to me that Micky must have struck his pure gold for, in a few sentences, Jill-Beth had described Kassouli’s threat and, with any luck, all that damning evidence must be spooling silently on to the take-up reel of Micky’s recorder. All I had to do now was cross the Ts and dot the Is. “And Kassouli won’t do that if I sail on Wildtrack? ”

“Right.” She said it encouragingly, as though I was a slightly dumb pupil who needed to be chivvied into achievement. “Because we need your help, Nick! You’re our one chance. Persuade Bannister to take you as Wildtrack ’s navigator, and count your money!” It seemed odd to me that Yassir Kassouli, with all his millions, could only rely on me, but perhaps Jill-Beth was right. My arrival at Bannister’s house must have seemed fortuitous, so perhaps that explained her eagerness. I was a very convenient weapon to Bannister’s enemies, if I chose to be so. “And exactly what do I have to do?” I wanted her to spell it out for the microphone.

She showed no impatience at the pedantic question. “You just navigate a course that we’ll provide you.”

“What course?”

“Jesus! How do we know? That’ll depend on the weather, right?

All you have to do is keep a radio watch at the times we tell you, and that’s it. The easiest four hundred thousand you ever earned, right?”

I smiled. “Right.” That word, with its inflection of compliance, had been hard to say, yet I seemed to be convincing Jill-Beth with my act. And it was an act, a very amateur piece of acting in which I was struggling to invest each utterance with naturalness so that, consequently, my words sounded heavy and contrived. Yet, it occurred to me as I tried to seek my next line, Jill-Beth herself was just as mannered and awkward. I should have noted that with more interest, but instead I asked her what would happen when I had navigated Wildtrack to wherever I was supposed to take her.

“Nothing happens to you. Nothing happens to the crew.”

“But what happens to Bannister?”

“Whatever Yassir wants.” She said it slowly, almost as a challenge, then watched for my reaction.

I was silent for a few seconds. Jill-Beth’s words could be taken as an elliptical hint of murder, but I doubted whether she would be more explicit. I think she expected me to bridle at the hint, but instead I shrugged as though the machinations of Kassouli’s revenge were beyond me. “And all this,” I asked with what I thought was a convincing tone of reluctant agreement, “on the assumption that Bannister murdered his wife?”

“You got it, Nick. You want the hundred thousand now?” I should have said yes. I should have accepted it, but I baulked at the gesture. It might have been a necessary deception, but the entrapment was distasteful.

“For Christ’s sake, Nick! Are you going to help us or not?” Jill-Beth thrust the handbag towards me. “You want it? Or are you just wasting my time?”

I was about to accept, knowing the money was the final proof that Micky needed, when a strangled shout startled me. It was a man’s cry, full of pain.

I turned, but instantly, and treacherously, my right leg numbed and collapsed. I fell and Jill-Beth ran past me. I cursed my leg, knelt up, and forced myself to stand. I used my hands to straighten my right leg, then, half limping and half hopping, staggered on from tree to tree. I wondered whether my leg would always collapse at moments of stress.

I found Jill-Beth twenty yards further on, stooping, and I already knew what it was she crouched beside.

It was Micky. There was fresh vivid blood on his scalp, on his wet shirt, and on his hands. He was alive, but unconscious and breathing very shallowly. He was badly hurt. The bag lay spilt beside him and I saw the radio receiver but no sign of the small tape-recorder.

Whoever had hit Micky had also stolen the evidence.

“Did you bring him?” Jill-Beth looked at me accusingly.

“Get an ambulance.” I snapped it like a military order.

“Did you bring—”

“Run! Dial 999. Hurry!” She would be twice as fast as I could be.

“And bring blankets from the pub!”

She ran. I knelt beside Micky and draped my jacket over him. I tore a strip of cotton from my shirt-tail and padded it to staunch the blood that flowed from his scalp. Head wounds always bleed badly, but I feared this was more than a cut. He’d been hit with too much power, and I suspected a fractured skull. Blood had soaked into the dry brown needles that now looked black in the encroaching and damp twilight. I stroked his hand for, though he was unconscious, he would need the feel of human warmth and comfort.

I felt sick. I’d guarded Sycorax against Kassouli, but I had not thought to guard Micky. So who had done this? Kassouli? Had Jill-Beth brought reinforcements? Had she suspected that I might try to blow Kassouli’s scheme wide open? Those questions made me wonder whether she would phone an ambulance and, leaving Micky for a few seconds, I struggled to the edge of the trees and stared towards the village. My right leg was shaking and there was a vicious pulsing pain in my spine. I wasn’t sure I could limp all the way to the village, but if Jill-Beth let me down then I would have to try.

I cursed my leg, massaged it, then, as I straightened up, I saw headlights silhouetting running figures at the bridge. I limped back to Micky. He was still breathing, grunting slightly.

Footsteps trampled into the trees. Efficient men and women, trained to rescuing lost hikers from the moors, came to Micky’s rescue. There was no need to wait for an ambulance for there was a Rescue Land-Rover nearby which could take him to hospital. He was carefully lifted on to a stretcher, wrapped in a space blanket, and given a saline drip.

I limped beside him to the Land-Rover and watched it pull away towards the road. Someone had phoned the police and now asked me if I’d wait for their arrival. I said I wanted to go to the hospital, then remembered that Micky still had the car keys.

Читать дальше