Death of Kings

by Bernard Cornwell

Dedication

Death of Kings is for

Anne LeClaire,

Novelist and Friend,

who supplied the first line.

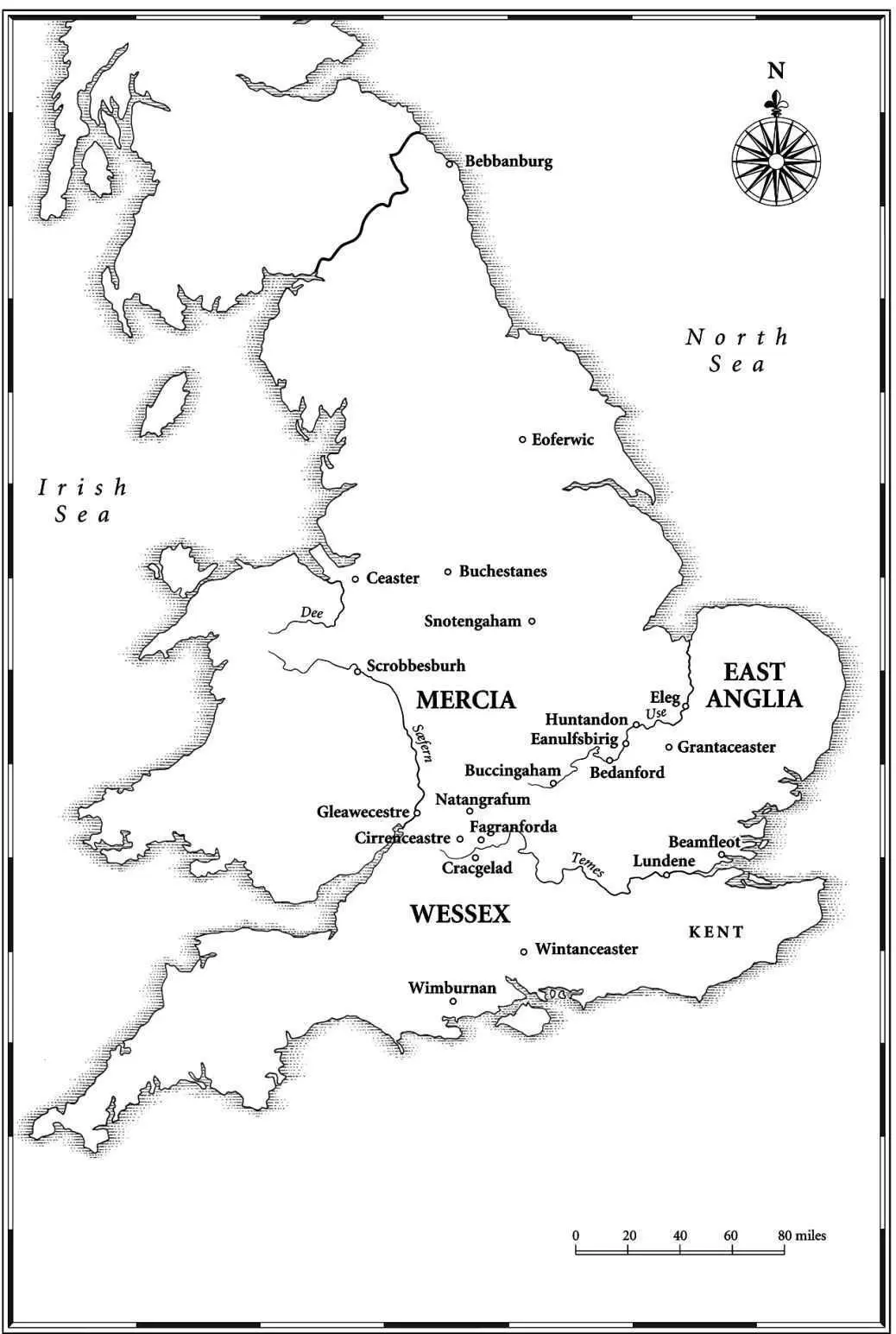

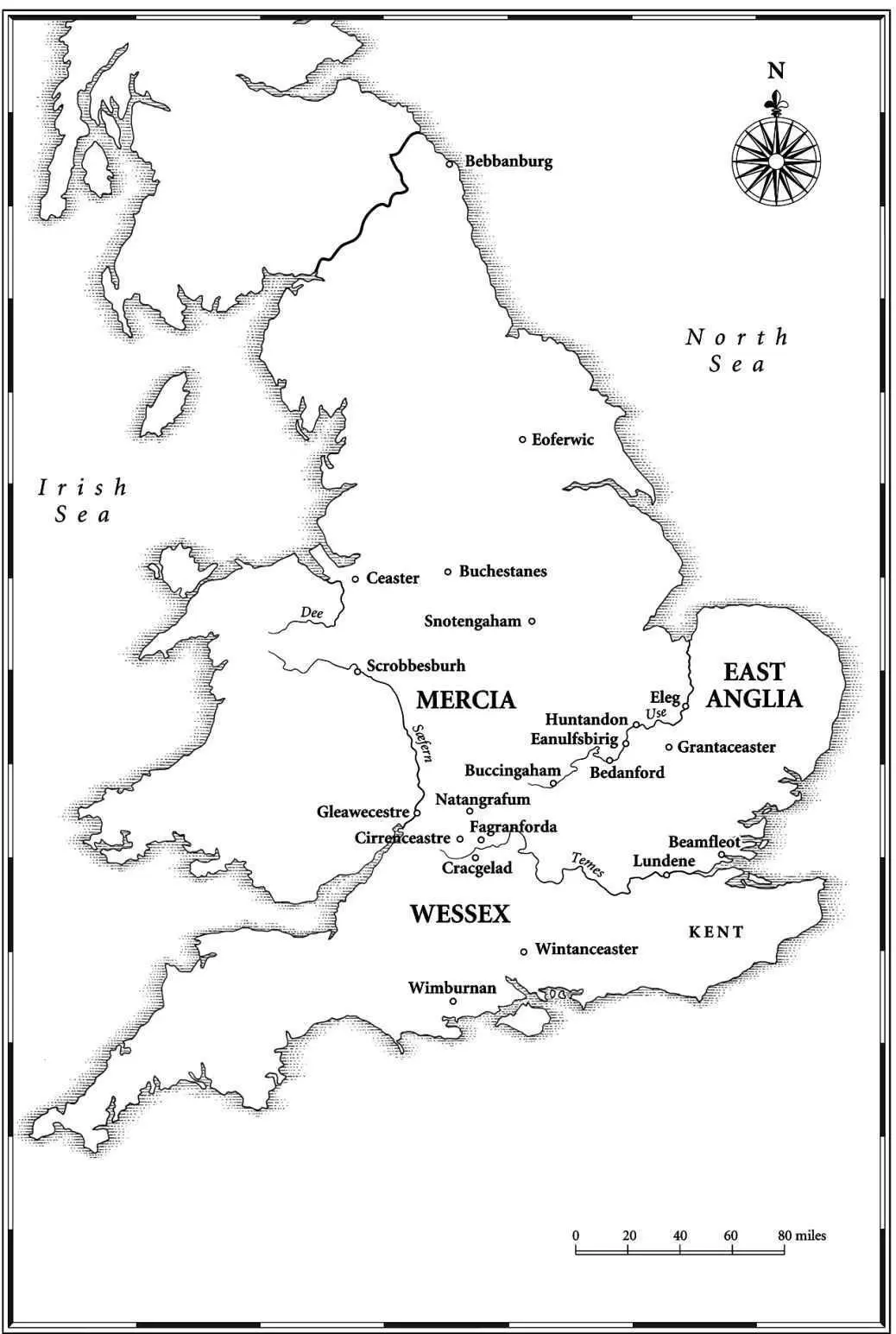

The spelling of place names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest to AD 900, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I should spell England as Englaland, and have preferred the modern form Northumbria to N  rhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

rhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

Baddan Byrig — Badbury Rings, Dorset

Beamfleot — Benfleet, Essex

Bebbanburg — Bamburgh, Northumberland

Bedanford — Bedford, Bedfordshire

Blaneford — Blandford Forum, Dorset

Buccingahamm — Buckingham, Bucks

Buchestanes — Buxton, Derbyshire

Ceaster — Chester, Cheshire

Cent — County of Kent

Cippanhamm — Chippenham, Wiltshire

Cirrenceastre — Cirencester, Gloucestershire

Contwaraburg — Canterbury, Kent

Cracgelad — Cricklade, Wiltshire

Cumbraland — Cumberland

Cyninges Tun — Kingston upon Thames, Greater London

Cytringan — Kettering, Northants

Dumnoc — Dunwich, Suffolk

Dunholm — Durham, County Durham

Eanulfsbirig — St Neot, Cambridgeshire

Eleg — Ely, Cambridgeshire

Eoferwic — York, Yorkshire (called Jorvik by the Danes)

Exanceaster — Exeter, Devon

Fagranforda — Fairford, Gloucestershire

Fearnhamme — Farnham, Surrey

Fifhidan — Fyfield, Wiltshire

Fughelness — Foulness Island, Essex

Gegnesburh — Gainsborough, Lincolnshire

Gleawecestre — Gloucester, Gloucestershire

Grantaceaster — Cambridge, Cambridgeshire

Hothlege, River — Hadleigh Ray, Essex

Hrofeceastre — Rochester, Kent

Humbre, River — River Humber

Huntandon — Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire

Liccelfeld — Lichfield, Staffordshire

Lindisfarena — Lindisfarne (Holy Island), Northumberland

Lundene — London

Medwæg, River — River Medway, Kent

Natangrafum — Notgrove, Gloucestershire

Oxnaforda — Oxford, Oxfordshire

Ratumacos — Rouen, Normandy, France

Rochecestre — Wroxeter, Shropshire

Sæfern — River Severn

Sarisberie — Salisbury, Wiltshire

Sceaftesburi — Shaftesbury, Dorset

Sceobyrig — Shoebury, Essex

Scrobbesburh — Shrewsbury, Shropshire

Snotengaham — Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

Sumorsæte — Somerset

Temes, River — River Thames

Thornsæta — Dorset

Tofeceaster — Towcester, Northamptonshire

Trente, River — River Trent

Turcandene — Turkdean, Gloucestershire

Tweoxnam — Christchurch, Dorset

Westune — Whitchurch, Shropshire

Wiltunscir — Wiltshire

Wimburnan — Wimborne, Dorset

Wintanceaster — Winchester, Hampshire

Wygraceaster — Worcester, Worcestershire

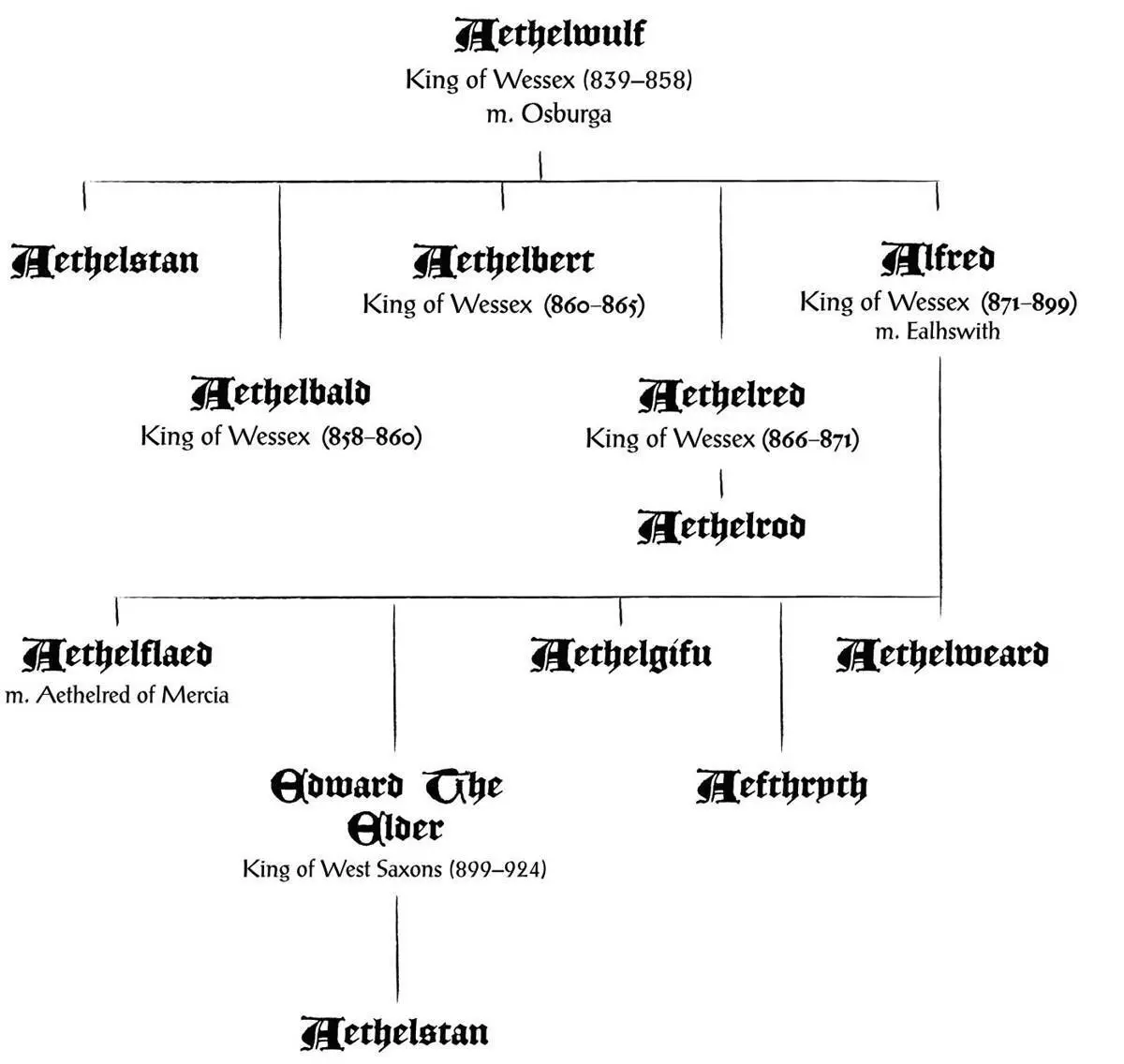

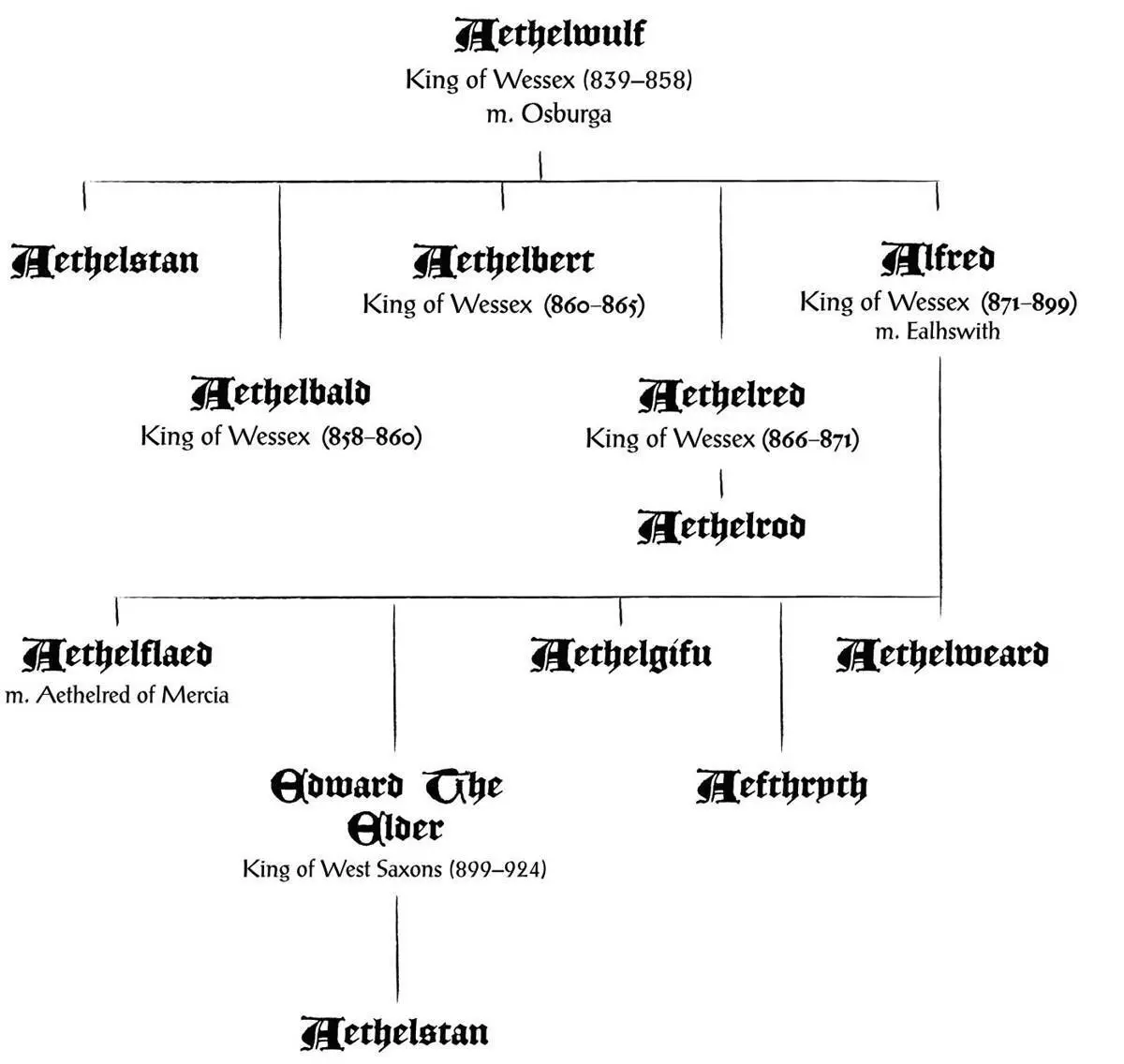

The Royal Family of Wessex

‘Every day is ordinary,’ Father Willibald said, ‘until it isn’t.’ He smiled happily, as though he had just said something he thought I would find significant, then looked disappointed when I said nothing. ‘Every day,’ he started again.

‘I heard your drivelling,’ I snarled.

‘Until it isn’t,’ he finished weakly. I liked Willibald, even if he was a priest. He had been one of my childhood tutors and now I counted him as a friend. He was gentle, earnest, and if the meek ever do inherit the earth then Willibald will be rich beyond measure.

And every day is ordinary until something changes, and that cold Sunday morning had seemed as ordinary as any until the fools tried to kill me. It was so cold. There had been rain during the week, but on that morning the puddles froze and a hard frost whitened the grass. Father Willibald had arrived soon after sunrise and discovered me in the meadow. ‘We couldn’t find your estate last night,’ he explained his early appearance, shivering, ‘so we stayed at Saint Rumwold’s monastery,’ he gestured vaguely southwards. ‘It was cold there,’ he added.

‘They’re mean bastards, those monks,’ I said. I was supposed to deliver a weekly cartload of firewood to Saint Rumwold’s, but that was a duty I ignored. The monks could cut their own timber. ‘Who was Rumwold?’ I asked Willibald. I knew the answer, but wanted to drag Willibald through the thorns.

‘He was a very pious child, lord,’ he said.

‘A child?’

‘A baby,’ he said, sighing as he saw where the conversation was leading, ‘a mere three days old when he died.’

‘A three-day-old baby is a saint?’

Willibald flapped his hands. ‘Miracles happen, lord,’ he said, ‘they really do. They say little Rumwold sang God’s praises whenever he suckled.’

‘I feel much the same when I get hold of a tit,’ I said, ‘so does that make me a saint?’

Willibald shuddered, then sensibly changed the subject. ‘I’ve brought you a message from the ætheling,’ he said, meaning King Alfred’s eldest son, Edward.

‘So tell me.’

‘He’s the King of Cent now,’ Willibald said happily.

‘He sent you all this way to tell me that?’

‘No, no. I thought perhaps you hadn’t heard.’

‘Of course I heard,’ I said. Alfred, King of Wessex, had made his eldest son King of Cent, which meant Edward could practise being a king without doing too much damage because Cent, after all, was a part of Wessex. ‘Has he ruined Cent yet?’

‘Of course not,’ Willibald said, ‘though…’ he stopped abruptly.

‘Though what?’

‘Oh it’s nothing,’ he said airily and pretended to take an interest in the sheep. ‘How many black sheep do you have?’ he asked.

‘I could hold you by the ankles and shake you till the news drops out,’ I suggested.

‘It’s just that Edward, well,’ he hesitated, then decided he had better tell me in case I did shake him by the ankles, ‘it’s just that he wanted to marry a girl in Cent and his father wouldn’t agree. But really that isn’t important!’

I laughed. So young Edward was not quite the perfect heir after all. ‘Edward’s on the rampage, is he?’

‘No, no! Merely a youthful fancy and it’s all history now. His father’s forgiven him.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

rhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

rhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.