“Scuttles,” I insisted. They were beautifully made, with thick greenish glass and heavy brass frames. They had hinged shutters that could be bolted down in bad weather.

I screwed and caulked the scuttles home. Beneath them I was rebuilding the cabin. I made two bunks, a big chart table and a galley.

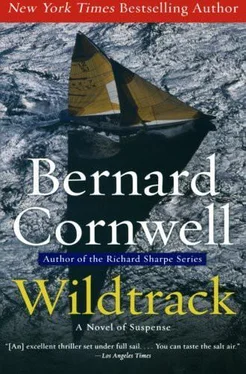

I turned the forepeak into a workshop and sail locker. I built a space for a chemical loo and Angela wanted to know why I didn’t put in a proper flushing loo like the ones on Wildtrack and I said I didn’t want any unnecessary holes bored in Sycorax ’s hull. Why bother with a loo at all, she asked tartly, why not just buy an extra bucket?

I said that the girls I planned to live with liked to have something more than a zinc bucket. She hit me.

The sails were repaired in a Dartmouth loft and came back to the boat on a day when the film crew was absent. Jimmy and I could not resist bending mizzen and main on to their new spars. The sails had to be fully hoisted if they were to be properly stowed on the booms and I felt the repaired hull shiver beneath me as the wind stirred the eight-ounce cotton. “We could take her out?” Jimmy suggested slyly.

I wound the gaff halliard off its belaying pin and lowered the big sail. “We’ll wait, Jimmy.”

“Put on staysails, boy. Let’s see how her runs, eh?” I was tempted. It was a lovely day with a south-westerly wind gusting to force five and Sycorax would have revelled in the sea, but I’d promised Angela I’d wait so that the film crew could record my first outing in the rebuilt boat. I lifted the boom and gaff so Jimmy could unclip the topping lift and thread the sail cover into place.

He hesitated. “Are you sure, boy?”

“I’m sure, Jimmy.”

He pushed the cover on to the stowed sail. “It’s that maid, isn’t it? Got you right under her thumb, she do.”

“I promised her I’d wait, Jimmy.”

“You keep your brains in your trousers, you do, Nick. When I was a boy, a proper man wouldn’t let a maid near his boat. It means bad luck, letting a woman run a boat.”

I straightened up from the belaying pin. “So what about Josie Woodward? Who put her in the club three miles off Start Point?” He laughed wickedly and dropped the subject. I promised him it would only be a day or two, no more, before we could film the sequence I had dreamed of for so long; the moment when Sycorax sailed again. Two months before, I reflected, I would have taken Jimmy’s hint and we would have taken the old boat out to sea and debated whether ever to come back again, but now I was as committed to the film as Angela herself. I had even begun to see it through her eyes, though I still refused to contemplate sailing on the St Pierre, and Angela had agreed that we’d devise a different ending for the film; one with Sycorax beating out to sea.

I telephoned Angela at her London office that afternoon. “She’s all ready,” I said. “Sails bent on, ma’am, ready to go.”

“Completely ready?”

“No radio, no navigation lights, no stove, no barometer, no chronometer, no compass, no bilge pumps, no anchors, no radar reflector, no…” I was listing all the things Fanny Mulder had stolen.

“They’re ordered, Nick,” Angela said impatiently.

“But she can sail,” I said warmly. “ Sycorax is ready for sea. She awaits your bottle of champagne and your film crew.”

“That’s wonderful.” Angela did not sound very pleased, perhaps because I was finishing a boat that would take me away from her, which made my own enthusiasm tactless. There was a pause. “Nick?”

“There’s a train that leaves Totnes at twenty-six minutes past five this afternoon,” I said, “and it reaches London at—”

“Twenty-five minutes to nine,” she chimed in, and did sound pleased.

“I suppose I could just make it.” I made my voice dubious.

“You’d bloody well better make it,” she said, “or there’ll be no radio, no navigation lights and no stove.”

“Bilge pumps?”

She pretended to think about it. “Definitely no bilge pumps. Ever.” I made it.

Angela’s flat was a gloomy basement in Kensington. She only used it when Bannister was away, but the very fact that she had retained the flat spoke for her independence. At least I thought so. The flat had a somewhat abandoned feel. It was sparsely furnished, the plants had all long died of thirst, and dust was thick on shelves and mantelpiece. Papers and books lay in piles everywhere. It was the flat of a busy young woman who spent most of her time elsewhere.

“Next Tuesday,” she told me.

“What about it?”

“That’s when we’ll film Sycorax going to sea.”

“Not till then?”

She must have heard my disappointment. “Not till then.” She was sitting at her dressing-table wiping off her make-up. “We can’t do it till Tuesday because Monday’s the travelling day for the crew.”

“Why can’t they travel on Sunday?”

“You want to pay them triple time? Just be patient till Tuesday, OK?”

“High tide’s at ten forty-eight in the morning,” I said from memory, “and it’s a big one.”

“Does that matter?”

“That’s good. We’ll go out on a fast ebb.”

She leaned towards the mirror to do something particularly intricate to an eyelid. “There’s another reason it has to be Tuesday,” she said, and I heard the edge of strain in her voice.

“Go on.”

“Tony wants to be there.” She did not look at me as she spoke.

“It’s important that he’s there. I mean, the film is partly about how he helped you, isn’t it? And he wants to see Sycorax go to sea.”

“Does he want to be on board?”

“Probably.”

I lay in her bed, saying nothing, but feeling jealousy’s tug like a foul current threatening a day’s perfection. It was stupid to feel it, but natural. I knew that Angela’s prime loyalty was to Bannister, yet I resented it. I had lived these past weeks in a mist of happiness, revelling in the joys of a new love’s innocence, and now the real world was snapping shut on me. This present happiness was an il-lusion, and Bannister’s return was a reminder that Angela and I shared nothing but a bed and friendship.

She turned in her chair. She knew what I was thinking. “I’m sorry, Nick.”

“Don’t be.”

“It’s just that…” she shrugged, unable to finish.

“He has prior claim?”

“I suppose so.”

“And you have no choice?” I asked, and wished that I had not asked because I was betraying my jealousy.

“I’ve got choice.” Her voice was defiant.

“Then why don’t we sail Sycorax out on Sunday.” On Sunday Bannister would still be in France, even though Wildtrack had sailed for home three weeks before. “You come with me,” I said. “We’ll be in the Azores in a few days. After that we can make up our minds.

You want to see Australia again? You fancy exploring the Caribbean?”

She twisted her long hair into a hank that she laid up on her skull.

“I get sea-sick.”

“You’ll get over it in three days.”

“I never get over it.” She was staring into the mirror as she pinned up her hair. “I’m not a sailor, Nick.”

“People do get over it,” I said. “It takes time, but I promise it doesn’t last.”

“Nick!” I was pressing her too hard.

“I’m sorry.”

She stared at herself in the mirror. “Do you think I haven’t been tempted to get away from it all? No more of Tony’s insecurity, no more jealousy at work, no more sodding around with schedules and film stocks and worrying where the next good idea for a programme will come from? But I can’t do that, Nick, I can’t! If I was twenty years old I might do it. Isn’t that the age when people think the world will lap them in love and all they need do is show a little faith in it?

Читать дальше