“I don’t know.” I hesitated, and Kassouli let the silence stretch uncomfortably. “There’s a rumour,” I said weakly, “that Mulder lied to the inquest, but it’s only pub gossip.”

“Which also says that Bannister was the man on deck.” Kassouli, who had clearly known about the rumour all along, pounced hard on me as though he was nailing the truth at last. “Why, in the name of God, would they lie about that?” I was beginning to regret that I had come to America. It had seemed like a blithe adventure when Jimmy had delivered the ticket to Sycorax , but now the trip had turned into a very uncomfortable inquisition. “We don’t know that it was a lie,” I said.

“You would let sleeping dogs dream,” Kassouli said scathingly,

“because you fear their bite.”

I feared Kassouli’s bite more. He was not a sleeping dog, but a very wideawake wolf. “There is something else.” Kassouli closed his eyes for a few seconds, as if his next statement was painful. “My daughter, I believe, was in love with another man.”

“Ah.” It was an inadequate response, but my Army training was not up to any other reaction. I could discuss the sea with a fair equanimity, but I was discomforted by this new, embarrassing and personal strain in the conversation.

Kassouli, oblivious to my embarrassment, turned to his son. “Tell him, Charles.”

Charles Kassouli shrugged. “She told me.”

“Told you what?” I asked.

“There was another fellow.” He was laconic, and his voice was very slightly slurred.

“But she did not say who he was?” his father asked.

“No. But she was kind of excited, you know?” I did know, but I kept from looking at Jill-Beth. “Isn’t it odd,” I said instead, “that she sailed with her husband if she was in love with someone else?”

“Nadeznha was not a girl to lightly dismiss a marriage,” Kassouli said. “She would have found divorce very painful. And, indeed, she shared her husband’s ambition to win the St Pierre. It was a mistake, Captain. She sailed to her murder.”

He waited once more for me to chime in with an agreement that her death had been murder. I’d even been fetched clean across the Atlantic to provide that agreement, but I did not oblige.

Kassouli gave the smallest shrug. “May I tell you about Nadeznha, Captain?”

“Please.” I was excruciatingly embarrassed.

He stood and paced the rug. Sometimes, as he spoke, he would glance at the family photograph. “She was a most beautiful girl, Captain. You would expect a father to say that of his daughter, yet I can put my hand on my heart and tell you that she was, in all honesty, a most outstanding young lady. She was clever, modest, kind and accomplished. She had a great trust in the innate decency of all people. You might think that naivety, but to Nadeznha it was a sacred creed. She did not believe that evil truly existed.” He stopped pacing and stared at me. “She was named after my mother”—he added the apparent irrelevance—“and you would have liked her.”

“I’m sure,” I said lamely.

“Nadeznha was a good person,” Kassouli said very firmly as if I needed to understand that encomium before he proceeded. “I believe that I spoilt her as a child, yet she possessed a natural balance, Captain; a feel for what was right and true. She made but one mistake.”

“Bannister.” I helped the conversation along.

“Exactly. Anthony Bannister.” The name came off Kassouli’s tongue with an almost vicious intensity; astonishing from a man whose tones had been so measured until this moment. “She met him shortly after she had been disappointed in love, and she married him on what, I believe, is called the rebound. She was dazzled by him. He was a European, he was famous in his own country, and he was glamorous.”

“Indeed.”

“I warned her against a precipitate marriage, but the young can be very headstrong.” Kassouli paused, and I noted this first betrayal of a crack in the perfect image he had presented of his daughter. He looked hard at me. “What do you think of Bannister?”

“I really don’t know him well.”

“He is a weak man, a despicable man, Captain. I take no pleasure in thus describing one of your countrymen, but it is true. He was unfaithful to my daughter, he made her unhappy, and yet she persisted in offering him the love and loyalty which one would have expected from a girl of her sweet disposition.”

There was confusion here. A sweet girl? But headstrong and wilful too? There was no time to pursue the confusion, even if I had wanted to, for Kassouli turned on me with a direct challenge. “Do you believe my daughter was murdered, Captain Sandman?” I sensed Jill-Beth and the crippled son waiting expectantly for my answer. I knew what answer they wanted, but I was wedded to the truth and the truth was all I would offer. “I don’t know how Nadeznha died.”

The truth was not enough. I saw Yassir Kassouli’s right hand clenching in spasms and I wondered if I had angered him. The son made a hissing noise and Jill-Beth stiffened. I was among believers, and I had dared to express disbelief.

Yet if Kassouli was angry, his voice did not betray it. “I only have two children, Captain Sandman. My son you see, my daughter you will never see.”

The grief was suddenly palpable. I hurt for this man, but I could not offer him what he wanted—agreement that his beloved daughter had been murdered. Perhaps she had been, but there was no proof.

I was prepared to admit that it was unlikely that Nadeznha Bannister had been unharnessed in a stiff sea, I could even say that it was possible she had been pushed overboard, but such lukewarm support was of no use to Yassir Kassouli. I was in the presence of an enormous grief; the grief of a man who could buy half the world, but could not control the death of a child he had loved.

“It was murder,” Kassouli said to me now, “but it was the perfect murder. That means it cannot be proved.”

I opened my mouth to speak, found I had nothing to say, so closed it again.

“But just because a murder is perfect,” Kassouli said, “does not mean that it should go unavenged.”

I needed to move, for the sofa’s rich comfort and the man’s heavy gaze were becoming oppressive. I stood and limped to the room’s far end where I pretended to stare at a model of a supertanker. She was called the Kerak . It struck me, as I stared at the striking kestrel on her single smokestack, that despite Kassouli’s Mediterranean birth he had one very American trait; he believed in perfection. The Mayflower had brought that belief in her baggage, and the dream had never been lost. To Americans Utopia is always possible; it will only take a little more effort and a little more goodwill. But a large part of Yassir Kassouli’s dream had died in the North Atlantic, in nearly two thousand fathoms of cold water. I turned. “You need proof,” I said firmly.

He shook his head. “I need your help, Captain. Why else do you think I brought you here?”

“I—”

He cut me off. “Bannister has asked you to navigate for him?”

“I’ve refused him.”

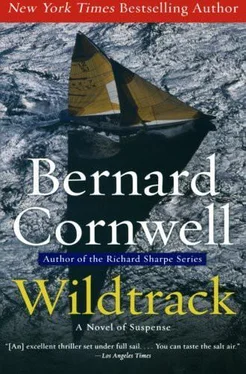

Kassouli ignored the words. “I will pay you two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, Captain Sandman, if, on the return leg of the St Pierre, you navigate the Wildtrack on a course that I will provide you.”

Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. The sum hung in the air like a monstrous temptation. It spelt freedom from everything; it would give Sycorax and me the chance to sail till the seas ran dry.

Kassouli mistook my hesitation. “I do assure you, Captain, that your life, and the lives of the Wildtrack ’s crew, will be entirely safe.” I did not doubt it, but I noted how one man’s name was excepted from that promise of mercy; Bannister’s. I’d known Kassouli was Bannister’s enemy, now I saw that the American would not be content until his enemy was utterly and totally destroyed. Something primeval, almost tribal, was at work here. A tooth for a tooth, an eye for an eye, and now a life for a life.

Читать дальше