He crossed to the table and lifted the photograph. “Before the tragedies. You met my son?”

“Indeed, sir.” The ‘sir’ came quite naturally.

“I raised my children according to Western tenets, Captain Sandman. To my daughter I gave freedom, and to my son pleasure. I do not think, on the whole, that I did well.” He said the last words drily, then crossed to a liquor cabinet. “You drink Irish whisky, I believe.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Jameson or Bushmills?” He had a New England accent. If it had not been for his name, and for the very dark eyes, I’d have taken him for a Wasp broker or banker.

“Either.”

He poured my whiskey, then helped himself to Scotch. As he finished pouring, the door opened and his son, escorted by Jill-Beth, wheeled himself into the room. Kassouli acknowledged their arrival by a gesture suggesting they helped themselves to liquor. “You don’t mind, Captain, if my son joins us?”

“Of course not, sir.”

He brought me my whisky that had been served without ice in a thick crystal glass. “Allow me to congratulate you on your Victoria Cross, Captain. I believe it is a very rare award these days?”

“Thank you.” I felt clumsy in the face of his suave courtesy.

“Do you smoke, Captain Sandman?”

“No, sir.”

“I’m glad. It’s a filthy habit. Shall we sit?” He gestured at the sofas in front of the fireplace.

We sat. Jill-Beth and Charles Kassouli positioned themselves at the back of the room, as if they knew they were present only to ob-serve. The son’s earlier and surly defiance had been muted to a respectful silence and I suspected that Charles Kassouli lived in some fear of his formidable father. He certainly did not light a cigarette in his father’s presence.

Yassir Kassouli thanked me for rescuing Jill-Beth. He thanked me again for coming to America. He spoke for a few minutes of his own history, of how he had purchased two tank-landing craft at the end of the Second World War and used them to found his present fortunes. “Most of that fortune,” he said in self-deprecation, “was based on smuggling. A man could become very rich carrying cigarettes from Tangiers to Spain in the late forties.

Naturally, when I became an American citizen, I gave up such a piratical existence.”

He asked after my father and expressed his regrets at what had happened. “I knew Tommy,” he said, “not well, but I liked him. You will pass on my best wishes?” I promised I would. Kassouli then enquired what my future was, and smiled when I said that it depended on ocean currents and winds. “I’ve often wished I could be such an ocean gypsy myself,” Kassouli said, “but alas.”

“Alas.” I echoed him.

The word served to make him look at his family portrait. I watched his profile, seeing the lineaments of the thin, savage face that had become fleshy with middle age. “In my possession,” he said suddenly, “I have the weather charts and satellite photographs of the North Atlantic for the week in which my daughter was killed.”

“Ah.” The suddenness with which he had introduced the subject of his daughter’s death rather wrong-footed me.

“Perhaps you would like to see them?” He clicked his fingers and Jill-Beth dutifully opened a bureau drawer and brought me a thick file of papers.

I spilt the photographs and grey weatherfax charts on to my lap.

Each one was marked with a red-ink cross to show where Nadeznha Bannister had died. I leafed through them as Kassouli watched me.

“You’ve sailed a great deal, Captain Sandman?” he asked me.

“Yes, sir.”

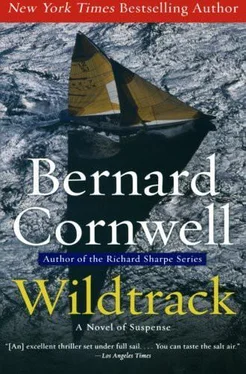

“Would you, from your wide experience, say that the conditions revealed in those photographs were such that a large boat like Wildtrack might have been pooped?” Kassouli still spoke in his measured, grave voice, as though, instead of talking about his daughter’s death, he spoke of politics or the Stock Market’s vagaries.

I insisted on looking through all the papers before I answered.

The sequence of charts and photographs showed that Wildtrack had been pursued, then overtaken, by a small depression that had raced up from New England, crossed the Grand Banks, then clawed its way out into the open ocean. The cell of low pressure would have brought rain, a half gale, and fast sailing, but the isobars were not so closely packed as to suggest real storm conditions. I said as much, but added that heavy seas were not always revealed by air pressure.

“Indeed not,” Kassouli acknowledged, “but two other boats were within a hundred miles, and neither reported exceptional seas.” I shuffled the photographs with their telltale whirl of dirty cloud.

“Sometimes,” I said lamely, “a rogue wave is caused by a ship’s wake. A supertanker?”

“Miss Kirov’s researches have discovered no big ships in the vi-cinity that night.” Kassouli had the disconcerting trick of keeping his eyes quite steadily on mine.

“Even so,” I insisted, “rogue waves do happen.” Kassouli sighed, as though I was being deliberately perverse. “The best estimate of wave height, at that time and in that place, is fifteen feet. You wish to see the report I commissioned?” He clicked his fingers again, and Jill-Beth dutifully brought me a file that was stamped with the badge of one of America’s most respected ocean-ographic institutes. I turned the typed pages with their charts of wave patterns, statistics and random sample analyses. I found what I wanted at the report’s end: an appendix which insisted that rogue waves, perhaps two or three times the height of the surrounding seas, were not unknown.

“You’re insisting that such seas are frequent?” Kassouli challenged me.

“Happily very infrequent.” I closed the report and laid it on the sofa.

“I do not believe,” he spoke as though he summarized our discussion, “that Wildtrack was pooped.”

There was a pause. I was expected to comment, but I could only offer the bleak truth, instead of the agreement he wanted. “But you can’t prove that she wasn’t pooped?”

His face flickered, as though I’d struck him, but his courteous tone did not falter. “The damage to Wildtrack ’s stern hardly supports Bannister’s story of a pooping.”

I tried to remember the evidence given at the inquest. Wildtrack had lost her stern guardrails, and with them the ensign staff, danbuoys and lifebelts. That added up to superficial damage, but it would still have needed a great force to rip the stanchions loose. I shrugged. “Are you saying the damage was faked?” He did not answer. Instead he leaned back in his sofa and steepled his fingers. “Allow me to offer you some further thoughts, Captain.

My daughter was a most excellent and highly experienced sailor.

Do you think it likely that she would have been in even a medium sea without a safety harness?”

I saw that Kassouli’s son was leaning forward in his wheelchair, intent on catching every word. “Not unless she was re-anchoring the harness,” I said, “no.”

“You are asking me to believe”—Kassouli’s deep voice was scornful—“that a rogue wave just happened to hit Wildtrack in the two or three seconds that it took Nadeznha to unclip and move her harness?”

It sounded lame, but sea accidents always sound unlikely when they are calmly recounted in a comfortable room. I shrugged.

Kassouli still watched closely for my every reaction. “Have you seen the transcript of the inquest?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“It says that the South African, what was his name?” He clicked his fingers irritably, and Jill-Beth, speaking for the first time since she had come into the room, supplied the answer. “Mulder,” Kassouli repeated the name. “The report says Mulder was on deck when my daughter died. Do you believe that?”

Читать дальше