Hector felt ashamed that he’d taken advantage of the prince’s youthful bravado.

‘Then I suggest we land the cannon out of sight of the Sugala, so they have no idea what we’re doing,’ he said.

Mansur seemed to have accepted his prince’s decision. ‘There’s a small bay just around that spit of land over there. We’ve used it before as a campsite.’

He shouted an order and the paddlers began to turn the kora kora, heading away from Haar. As they retreated, they heard a final flurry of musket shots and a faint jeering from the defenders.

‘They’ve plenty of gunpowder to waste,’ commented Jezreel drily.

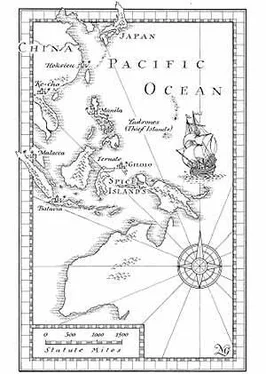

‘Probably got it from that same trader who sold it to the Sultan,’ said Hector. He was watching the coast ahead. He could already see the spit of land behind which the kora kora could shelter. ‘Jezreel, I think I should go ahead, while you and the others supervise the landing of the cannon. I want to scout that footpath we’ll be using. See if it’s as bad as Mansur claims, or if there’s some way we can get the five-pounder along it.’

LEAVING THE OTHERS on the beach, Hector headed inland. He had gone barely twenty yards when he began to appreciate just how difficult it would be to haul the cannon uphill. Had it not been for his guide, an Omoro warrior who had taken part in the previous expedition against Haar, he would never have guessed there was any sort of footpath through the jungle. He lost all sense of direction as he shouldered his way through thickets where the plants grew head-high, and his guide led him around the tangled roots of fallen trees piled awkwardly across one another. When that was impossible, he had to scramble over their massive rotting trunks, his hands sliding on the greasy coating of damp moss. Everywhere the ground was soggy, each footfall squelching into the thick layer of leaf mould. It was obvious the thick, eight-inch solid wooden wheels of the brass cannon’s carriage, designed to roll on a ship’s deck, would bog down and be useless in the jungle.

When at last they reached the stream whose course they had to follow, the conditions became even more awkward. It was impossible to stay on the bank. Shrubs and bushes forced Hector to step down into the water. The rocks in the stream bed shifted treacherously when he put his weight on them. Once or twice he tripped and fell forward, saving himself by throwing out his arms and plunging elbow-deep into the water. After twenty minutes of slow, bruising progress he reached the conclusion that Mansur was right. A short distance ahead of him the stream cascaded down a set of rapids, which an agile man might pass by clambering from one rocky shelf to the next, but it would be impossible to haul a heavy cannon up the cataract.

Disheartened, he paused to catch his breath. He felt insignificant within the immensity of the forest. Overhead the canopy of enormous trees blocked out the sunlight and any view of the sky. He was aware only of the constant sound of the rapids, the swirl of water rippling past his ankles, the musty smell of the damp earth, and the myriad itching insect pinpricks on his neck and arms.

The sudden loud, metallic cry of a large bird made him jump. It was a double squawk, very noisy and close at hand. The cry was repeated after a few seconds, then again, echoing through the jungle. From somewhere in the far distance, he heard an answering call. His Omoro guide had stopped abruptly a few yards ahead and held up a warning hand. Hector cautiously peered upwards, trying to see the bird. The nearest trees had straight trunks that soared upwards for at least eighty feet before spreading their mass of branches. They reminded him of the tall columns within a cathedral.

The metallic call came again, even closer. He looked towards his guide, who was making a dancing motion with both hands. ‘Manuk dewata,’ the man mouthed softly.

God’s Birds, Hector thought to himself. This was why he was here: to decide the rights of ownership over this green wilderness and the brilliant coloured plumage of the birds that lived within it. He scanned the jungle canopy, but could see nothing.

The next call was shockingly close by, no more than ten yards away. It came not from the branches high above him, but from the lip of the stream bank just to his right. He looked in that direction and, as he did so, a man stepped into view. He was, at most, five feet tall. Small-boned, with a thick bush of wiry black hair surrounding a head far too large for his body, he was completely naked except for a loincloth. He had a gourd hanging on a cord around his neck, and in his hand was a bamboo hoop to which clung three small, bright red and green parrots.

The extraordinary apparition looked at Hector and his companion for a long, slow interval. Then the grave face broke into a shy smile. Turning away from Hector, he faced into the jungle, lifted his free hand and pinched his nose. He took in a breath through his mouth and let loose a loud, metallic squawk through one nostril.

Somewhere in the distance the call was answered. The forest man was a bird hunter, tracking down his prey.

Cautiously Hector clambered up the bank and approached the stranger, careful not to frighten him. The little man had the manner of a timid forest creature who might suddenly take flight. ‘Salaam aleikum,’ Hector said gently. The man bobbed his head in a friendly way and stood his ground, but made no reply. The three gaily coloured parrots twittered and scrabbled on their perch, using beaks and claws to maintain their grip. Hector looked back enquiringly at his Omoro guide, who shrugged helplessly. It seemed the Omoro did not speak the newcomer’s language. Hector turned back to the bird catcher. ‘Is there a way to Haar from here?’ he asked in English. Large brown eyes regarded him wonderingly, and Hector thought to himself it was probably the first time the little man had seen someone with a pale skin and grey eyes. Hector raised his left hand, palm upwards, and made a walking motion across it with the fingers of his right hand. Then he pointed uphill and spread his arms wide, indicating a broader track.

The bird catcher considered for a moment, then beckoned Hector to follow. He turned and made his way between the trees, angling across the slope of the hill. Keeping up was difficult. The little man slipped nimbly through the forest, casually dangling his parrot perch. From time to time he paused and waited for Hector and his Omoro escort to catch up. Eventually, after some fifteen minutes, he came to a stop and pointed uphill. They were on the edge of what must have been a landslip some years earlier. A substantial section of the hillside had collapsed from the rim above and slid downslope. The torrent of rock and earth had swept away the taller trees and left a deep scar down the flank of the hill. They were standing at the midway point of the landslide, and, looking downslope to his right, Hector could see where the narrow coastal plain began.

Hector hid his disappointment. The gash in the forest caused by the landslide might once have provided an open track up the steep hill, but the undergrowth had grown back with tropical vigour in the intervening years. The way to the summit was now completely choked with a tangled mass of bushes, shrubs, saplings and ground creepers. It was impossible as a roadway for a heavy cannon.

‘Thank you, thank you very much,’ he said, nodding and smiling.

The bird catcher gave another of his shy smiles and gestured that he was willing to lead them towards the crest in the direction of Haar. But Hector had seen enough. He was despondent and tired, and it was time to return to the beach to report his findings. He shook his head and retraced his steps to where he had left the stream. The bird catcher darted ahead. Within moments he had outdistanced them and disappeared altogether. Hector slipped and slithered for another few paces until he again heard the metallic bird call. This time it definitely came from the treetops. Looking over to his right, he was astonished to see the bird catcher gazing down at him. The little man was perched forty feet off the ground on the branch of a huge tree, and was tying his parrots to the branches.

Читать дальше