Mansur bowed and made the customary introduction, but this time the Sultan did not invite the newcomers to share betel nut. Instead he sat silently for a long interval, blinking his rheumy eyes and staring malevolently at the foreigners. When eventually he spoke, Mansur translated in a low, obsequious voice.

‘His Majesty has been informed that your colleagues have stolen away in the night like thieves.’

‘We knew nothing of their plans,’ Hector answered.

‘You must have overheard them plotting this act of disobedience.’

‘They are not of our people. When they speak among themselves in their own language, neither I nor any of my companions know what they are saying.’

The Sultan shifted irritably on his cushions, crossing and recrossing his legs. He swayed back and forward slightly as if suffering from stomach cramps, then beckoned to one of his attendants, who came forward with a metal cup of water. The Sultan took a sip. Hector sensed the courtiers in the room behind him were holding their breaths, waiting for an outburst of royal rage. Seconds passed and the atmosphere grew more and more tense. Prince Jainalabidin was totally still, but stared at the visitors, his eyes glittering. Hector was reminded of a small, very poisonous viper about to strike.

Abruptly the Sultan let out a high-pitched cackle. The sound was unsettling, a demented gleeful noise, which ended in a series of watery coughs before the old man delivered his next pronouncement.

‘His Majesty says he is delighted that the Hollanders have gone,’ Mansur translated. Relief was evident in his tone. ‘His Majesty states they were useless mouths, expensive to feed, idlers who did not do any work.’

The Sultan’s eyes were streaming, the tears trickling down the grooves in his wrinkled face. An attendant hurried forward with a cloth. When the coughing had subsided and the Sultan had wiped his face, Prince Jainalabidin leaned across and whispered something in his father’s ear. The Sultan flapped the cloth towards Jezreel and wheezed a few words.

‘His Majesty says the big man is to join his troops. He is a skilful soldier, and Omoro needs good warriors,’ Mansur translated.

‘My companion has done some sword fighting in the prize ring, but he was never in the army,’ Hector answered. He was puzzled at how the Sultan had come to the idea that Jezreel was a professional military man. The Sultan’s next remark provided the answer.

‘That is not what my son tells me.’

Hector glanced at the young prince. Maria must have told the youngster that Jezreel was a soldier, he thought. She’d probably been trying to impress the lad with the importance of their captives, hoping they’d be better treated. The prince had been staring at them out of curiosity and boyish admiration, not with dislike.

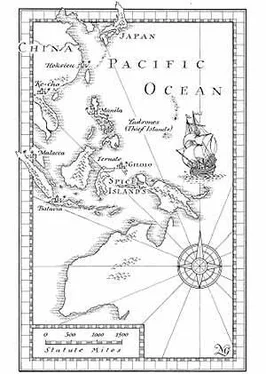

The Sultan spoke again. ‘His Highness Prince Jainalabidin has asked to lead another hongi-tochten against Sugala,’ translated Mansur. ‘He says that our men now have muskets that work properly and the Sugala will not be expecting a second attack this season. He will take them by surprise and teach them not to trespass on our forests.’ The old man glanced down at his son indulgently. ‘The prince is clever. He knows that the more bird skins we have to sell, the more traders will come to Omoro and the richer we will become. That way our kingdom will regain its former glory.’ The Sultan hawked into the cup from which he had been drinking. A lackey hurried forward to remove it from his shaking hand.

Hector thought quickly. A successful campaign against Sugala, with Jezreel taking a leading part, was the obvious chance to obtain the Sultan’s favour. He stole another look at the boy sitting beside the Sultan. He could see that Prince Jainalabidin was agog at the idea of leading another attack on Sugala. His eyes were shining with anticipation. It occurred to Hector that the youngster’s eagerness might just as quickly turn to disappointment and blame. It was more than likely Jezreel and his colleagues would be made the scapegoats if the new expedition was a failure. He recalled what the Malaccan trader had said: all previous campaigns against the Sugala had achieved nothing. Jezreel’s presence would make no difference.

He worded his answer carefully, hoping to discourage the idea of the new expedition, without contradicting what he thought were Maria’s claims about Jezreel’s prowess.

‘Your Majesty, I am sure my friend Jezreel is eager to serve you. I have been told that the Sugala are fearful of the Omoro and hide behind their walls.’

The Sultan reached out and laid a wizened hand fondly on his son’s shoulder.

‘His Majesty says his son is clever. He has already asked to take with him our lantaka to destroy their defences. Never before have our lantaka left Omoro, but His Majesty has given him permission to use them on this campaign.’

Hector hadn’t the slightest idea what the Sultan was talking about.

‘His Majesty says you and your companions will prepare the lantaka for the hongi-tochten,’ Mansur continued. ‘You will also be responsible for their safe return, so that they stand before the palace as proof of the high regard in which His Majesty is held by distant peoples.’

For a moment Hector could think only of the bizarre four-wheeled vehicle parked outside the palace. He failed to see how it could be used against the Sugala. Then he recalled the two bronze cannon on their wooden gun carriages. His heart sank. In his boyish enthusiasm, Prince Jainalabidin had come up with the notion of using these guns to batter down the Sugala defences. His idea was utterly impractical. The two guns were showpieces, presented a generation ago by foreigners seeking to gain favour with the Sultan. The weapons looked impressive, but they were little better than popguns. They might be good for firing a salute, or a shower of small shot that would tear into human flesh. But they had never been meant for serious warfare and certainly not as siege weapons.

He caught the gleam of triumph in the prince’s eye. The lad was feeling very pleased with himself, and Hector realized that he’d insult the youngster if he dismissed the ill-judged scheme out of hand. ‘An inspired suggestion,’ he said, then added what he hoped would be a practical objection. ‘We would need gunpowder of very good quality.’

The Sultan positively beamed at this new opportunity to boast of his son’s intelligence. ‘Prince Jainalabidin has told His Majesty that the jong from Malacca brought a dozen kegs of the best powder to exchange for our bird skins. His Majesty has given him permission to take as much of the gunpowder as he wants to make his attack on Sugala a success.’

Out of the corner of his eye Hector could see Dan looking across at him in astonishment. The Miskito had been following what was being said and knew how unrealistic the new scheme was. Yet Hector could see no tactful way to dampen the prince’s enthusiasm or deflect his father’s decision. So he bowed. ‘With your permission, my colleagues and I will begin to prepare the lantaka without further delay.’

The moment they were outside the portico, Dan hurried over to take a closer look at the lantaka. He stuck a finger into the muzzle of one of the guns. ‘Not even a one-inch bore,’ he commented wryly. He gave his friend a serious look. ‘The ball would bounce off the flimsiest palisade.’

Hector agreed. The lantaka were just three feet long. Their bronze castings had acquired a rich dark-green patina and were embellished with swirling floral patterns and whorls. Each rested on its heavy wooden sledge, made of some dark tropical wood. These gun carriages were exquisitely carved with patterns to mimic the guns’ decoration. It was as he’d feared: they were elegant, showy and of little practical use beyond firing salutes or scatter-shot.

Читать дальше