Jezreel stooped over one of the lantaka and put his massive arms under the barrel and the knob of the cascabel. He gave a grunt and lifted the weapon clean out of its carriage. ‘Well, no difficulty in taking it with us,’ he said with a grin.

Dan ignored him. He was looking thoughtful. ‘I suggest we clean up these pea-shooters and test-fire them to make sure the Malaccan gunpowder is of good quality.’

Jezreel lowered the gun back into its carriage. ‘Even if it turns out that the Malaccan is trading in shoddy goods, I get the impression the Sultan will still indulge his son and send out another expedition under his command.’

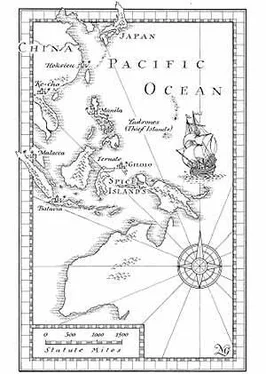

The Miskito did not appear to have heard him. He was looking out to sea, over the township and the harbour. ‘We could try using one of Captain Vlucht’s cannon to knock down the defences of the Sugala, provided they’re not stone-built. Let us hope that the Westflinge is still hung up on the reef.’

EIGHTEEN

CLEANED AND POLISHED, the lantaka made a brave show lashed securely to the foredeck of the kora kora. The little cannon gleamed in the early morning sunshine as the expedition headed out from Pehko. The Sultan’s purple banner was once again hoisted from the vessel’s stubby flagstaff, and the crew seated on their outrigger benches had caught the optimistic mood of the departure. They roared their work chant as they chopped at the water with their paddle blades. Through the soles of his feet Hector could feel each sudden surge as the kora kora was thrust forward, and he couldn’t help glancing back towards the Kedatun sultan high on the hillside. Mansur had told him that the royal women were required to stay out of sight whenever there were strangers in the palace, but at other times they were free to go about the building as they pleased. He was wondering if Maria was standing on the portico and watching the kora kora head out to sea.

‘Good morning. How are you?’ The question startled him. Prince Jainalabidin had emerged from the little hut-like cabin behind him and was addressing him in halting Spanish.

Hector overcame his surprise. He guessed the boy had received lessons from Maria. Clearly the youngster had a good ear and a quick intelligence. Here, at last, was a chance to find out how she was.

‘Your Highness speaks Spanish well. His teacher will be pleased.’

The lad flashed him a smile. ‘You are her man, yes?’

Hector had not expected Maria to have talked about him with her pupil. He felt a thrill of pleasure that she had done so.

‘Is Maria well?’ he asked.

‘My sisters her friends.’

The boy reached into a fold of his robe. ‘She say me to give you this,’ he said and pressed a scrap of paper into Hector’s hand.

Hector felt the blood rush to his head as he scanned the few lines of writing:

Dearest Hector,

I hear that you are well and that Captain Vlucht and the Hollanders have gone, but Dan and our other friends remain. I long to see you. News comes to me at second hand, and I am told that you will soon be leaving on an expedition of war. The prince speaks much about all of you and has agreed to give you this note. He is a good boy. Make sure that you come back safe, and that he does also. Do not worry about me for I am in good health, my days are comfortable and I will be waiting for your return. You have my love.

Maria.

The prince was watching for his reaction. Hector gave him a grateful look. ‘Thank you for bringing me this note. It has made me very happy.’

‘We come back, we have a . . .’ The lad’s voice trailed away as he searched for the right word. He beckoned to Mansur and spoke to him in his own language.

‘His Highness says that his father the Sultan has promised him a great victory celebration on his return to Pehko,’ Mansur translated for him.

‘My companions and I will do everything we can to make sure of that victory,’ Hector replied. He was not at all sure the expedition would be a success, and it felt very strange to be under the command of a child. He wondered again what the penalty would be if the expedition turned out to be a disaster.

THE WRECK OF the Westflinge came in view shortly before midday. The ship still lay crumpled across the reef. Even at a distance, it was clear that her back was now broken. The tall, narrow stern of the vessel had become detached and drifted a short distance from the rest of the hull, which was still impaled on the coral where she’d been abandoned. At the waterline the midships section had bulged, bursting open like a rotten melon. There was no sign of any of the three masts. They must have toppled overboard and been carried away by the current. The gnawing of the tide and the action of waves had searched out the wreck’s weaknesses and were prising her apart. There were breaches in her sides through which daylight showed. In places the planks had cracked off short, leaving jagged ends. The remaining timbers were dappled with blotches of black fungus.

The kora kora approached cautiously, a lookout in the bows searching for a clear passage between the coral heads, the paddlers barely dipping their blades into the water. Eventually, a hundred paces from the remains of the Westflinge, the lookout called a halt. The kora kora could approach no closer without risking her own fragile hull.

‘Hector, let us see if we can get at those guns. Best keep your boots on, or the coral will cut your feet,’ Dan advised. He was already pulling off his shirt, and a moment later was clambering down the outrigger struts and lowering himself into the warm, pale-green water. Hector followed him, and together they half-waded, half-swam towards the wreck. As they floundered forward, they could hear the suck and gurgle of the tide washing through the gaping holes in the Westflinge ’s side, and caught the flicker of small, brightly coloured fish that clustered near the hull, feeding on the growth of weed.

They came close enough to the wreck and circled round so that they could climb in through the open stern. Dan reached up and took hold of a plank’s end to pull himself inside. As he tugged, the plank broke off and he slipped back with a splash. He regained his feet and looked down at the fragment of wood still in his grasp. ‘Now we know why we couldn’t find any leak,’ he said. He held out the timber to show to his friend. The three-inch-thick piece of wood was riddled with passageways the thickness of a straw. Dotted amongst the passageways were small, pale shelly grubs smaller than a fingernail. Looking closer, Hector saw they were tiny, burrowing animals, each with a spiral-shaped head like a miniature drill.

‘Shipworm,’ declared Dan. ‘The hull is consumed with them. I am amazed she stayed afloat as long as she did. She must have been leaking in dozens of places.’

He reached out again and snapped off another chunk of wood. It came away in his hand like a section of honeycomb. Grimacing with disgust, he threw it into the sea. ‘In another couple of years there’ll be nothing left of her on this reef, except a few iron bolts and a pile of ballast stones.’

‘Not many of them, either. We dumped most of the ballast overboard,’ Hector reminded him.

Together they climbed through the opening and found themselves in the aft section of the hold. The water was up to their knees, and there was a reek of decay in the half-lit belly of the ship. Small, grey crabs scuttled up the curved frames of the hulk and fled into dark cracks in the timber as they waded carefully towards the companionway leading up to the deck. They trod gingerly. The footing was uneven where sections of plank had buckled inwards, and layers of seaweed and slime made the footing treacherous. They climbed the companionway – half the steps were missing – and emerged on the decaying deck. Skirting around the more obviously rotten patches, they made their way to the starboard gunwale. There, still lashed down to ring bolts, was one of the two cannon they’d kept back. Dan tapped the barrel. ‘That is lucky. Brass,’ he said. ‘Old-fashioned, but more durable. If it had been iron, we could have had a problem with the weight.’

Читать дальше