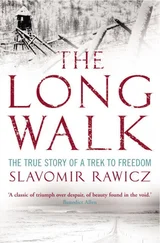

Nelson Mandela - The Long Walk to Freedom

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nelson Mandela - The Long Walk to Freedom» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Long Walk to Freedom

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Long Walk to Freedom: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Long Walk to Freedom»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Long Walk to Freedom — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Long Walk to Freedom», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

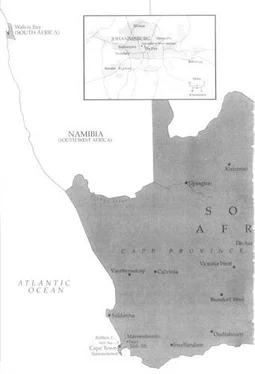

In that moment of beholding Jongintaba and his court I felt like a sapling pulled root and branch from the earth and flung into the center of a stream whose strong current I could not resist. I felt a sense of awe mixed with bewilderment. Until then I had had no thoughts of anything but my own pleasures, no higher ambition than to eat well and become a champion stick-fighter. I had no thought of money, or class, or fame, or power. Suddenly a new world opened before me. Children from poor homes often find themselves beguiled by a host of new temptations when suddenly confronted by great wealth. I was no exception. I felt many of my established beliefs and loyalties begin to ebb away. The slender foundation built by my parents began to shake. In that instant, I saw that life might hold more for me than being a champion stick-fighter.

* * *

I learned later that, in the wake of my father’s death, Jongintaba had offered to become my guardian. He would treat me as he treated his other children, and I would have the same advantages as they. My mother had no choice; one did not turn down such an overture from the regent. She was satisfied that although she would miss me, I would have a more advantageous upbringing in the regent’s care than in her own. The regent had not forgotten that it was due to my father’s intervention that he had become acting paramount chief.

My mother remained in Mqhekezweni for a day or two before returning to Qunu. Our parting was without fuss. She offered no sermons, no words of wisdom, no kisses. I suspect she did not want me to feel bereft at her departure and so was matter-of-fact. I knew that my father had wanted me to be educated and prepared for a wide world, and I could not do that in Qunu. Her tender look was all the affection and support I needed, and as she departed she turned to me and said, “Uqinisufokotho, Kwedini!” (Brace yourself, my boy!) Children are often the least sentimental of creatures, especially if they are absorbed in some new pleasure. Even as my dear mother and first friend was leaving, my head was swimming with the delights of my new home. How could I not be braced up? I was already wearing the handsome new outfit purchased for me by my guardian.

I was quickly caught up in the daily life of Mqhekezweni. A child adapts rapidly, or not at all — and I had taken to the Great Place as though I had been raised there. To me, it was a magical kingdom; everything was delightful; the chores that were tedious in Qunu became an adventure in Mqhekezweni. When I was not in school, I was a plowboy, a wagon guide, a shepherd. I rode horses and shot birds with slingshots and found boys to joust with, and some nights I danced the evening away to the beautiful singing and clapping of Thembu maidens. Although I missed Qunu and my mother, I was completely absorbed in my new world.

I attended a one-room school next door to the palace and studied English, Xhosa, history, and geography. We read Chambers English Reader and did our lessons on black slates. Our teachers, Mr. Fadana, and later, Mr. Giqwa, took a special interest in me. I did well in school not so much through cleverness as through doggedness. My own self-discipline was reinforced by my aunt Phathiwe, who lived in the Great Place and scrutinized my homework every night.

Mqhekezweni was a mission station of the Methodist Church and far more up-to-date and Westernized than Qunu. People dressed in modern clothes. The men wore suits and the women affected the severe Protestant style of the missionaries: thick long skirts and high-necked blouses, with a blanket draped over the shoulder and a scarf wound elegantly around the head.

If the world of Mqhekezweni revolved around the regent, my smaller world revolved around his two children. Justice, the elder, was his only son and heir to the Great Place, and Nomafu was the regent’s daughter. I lived with them and was treated exactly as they were. We ate the same food, wore the same clothes, performed the same chores. We were later joined by Nxeko, the older brother to Sabata, the heir to the throne. The four of us formed a royal quartet. The regent and his wife No-England brought me up as if I were their own child. They worried about me, guided me, and punished me, all in a spirit of loving fairness. Jongintaba was stern, but I never doubted his love. They called me by the pet name of Tatomkhulu, which means “Grandpa,” because they said when I was very serious, I looked like an old man.

Justice was four years older than I and became my first hero after my father. I looked up to him in every way. He was already at Clarkebury, a boarding school about sixty miles distant. Tall, handsome, and muscular, he was a fine sportsman, excelling in track and field, cricket, rugby, and soccer. Cheerful and outgoing, he was a natural performer who enchanted audiences with his singing and transfixed them with his ballroom dancing. He had a bevy of female admirers — but also a coterie of critics, who considered him a dandy and a playboy. Justice and I became the best of friends, though we were opposites in many ways: he was extroverted, I was introverted; he was lighthearted, I was serious. Things came easily to him; I had to drill myself. To me, he was everything a young man should be and everything I longed to be. Though we were treated alike, our destinies were different: Justice would inherit one of the most powerful chieftainships of the Thembu tribe, while I would inherit whatever the regent, in his generosity, decided to give me.

Every day I was in and out of the regent’s house doing errands. Of the chores I did for the regent, the one I enjoyed most was pressing his suits, a job in which I took great pride. He owned half-a-dozen Western suits, and I spent many an hour carefully making the crease in his trousers. His palace, as it were, consisted of two large Western-style houses with tin roofs. In those days, very few Africans had Western houses and they were considered a mark of great wealth. Six rondavels stood in a semicircle around the main house. They had wooden floorboards, something I had never seen before. The regent and the queen slept in the right-hand rondavel, the queen’s sister in the center one, and the left-hand hut served as a pantry. Under the floor of the queen’s sister’s hut was a beehive, and we would sometimes take up a floorboard or two and feast on its honey. Shortly after I moved to Mqhekezweni, the regent and his wife moved to the uxande (middle house), which automatically became the Great House. There were three small rondavels near it: one for the regent’s mother, one for visitors, and one shared by Justice and myself.

The two principles that governed my life at Mqhekezweni were chieftaincy and the Church. These two doctrines existed in uneasy harmony, although I did not then see them as antagonistic. For me, Christianity was not so much a system of beliefs as it was the powerful creed of a single man: Reverend Matyolo. For me, his powerful presence embodied all that was alluring in Christianity. He was as popular and beloved as the regent, and the fact that he was the regent’s superior in spiritual matters made a strong impression on me. But the Church was as concerned with this world as the next: I saw that virtually all of the achievements of Africans seemed to have come about through the missionary work of the Church. The mission schools trained the clerks, the interpreters, and the policemen, who at the time represented the height of African aspirations.

Reverend Matyolo was a stout man in his mid-fifties, with a deep and potent voice that lent itself to both preaching and singing. When he preached at the simple church at the western end of Mqhekezweni, the hall was always brimming with people. The hall rang with the hosannas of the faithful, while the women knelt at his feet to beg for salvation. The first tale I heard about him when I arrived at the Great Place was that the reverend had chased away a dangerous ghost with only a Bible and a lantern as weapons. I saw neither implausibility nor contradiction in this story. The Methodism preached by Reverend Matyolo was of the fire-and-brimstone variety, seasoned with a bit of African animism. The Lord was wise and omnipotent, but He was also a vengeful God who let no bad deed go unpunished.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Long Walk to Freedom»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Long Walk to Freedom» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Long Walk to Freedom» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.