Nelson Mandela - The Long Walk to Freedom

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nelson Mandela - The Long Walk to Freedom» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Long Walk to Freedom

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Long Walk to Freedom: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Long Walk to Freedom»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Long Walk to Freedom — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Long Walk to Freedom», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In later years, I discovered that my father was not only an adviser to kings but a kingmaker. After the untimely death of Jongilizwe in the 1920s, his son Sabata, the infant of the Great Wife, was too young to ascend to the throne. A dispute arose as to which of Dalindyebo’s three most senior sons from other mothers — Jongintaba, Dabulamanzi, and Melithafa — should be selected to succeed him. My father was consulted and recommended Jongintaba on the grounds that he was the best educated. Jongintaba, he argued, would not only be a fine custodian of the crown but an excellent mentor to the young prince. My father, and a few other influential chiefs, had the great respect for education that is often present in those who are uneducated. The recommendation was controversial, for Jongintaba’s mother was from a lesser house, but my father’s choice was ultimately accepted by both the Thembus and the British government. In time, Jongintaba would return the favor in a way that my father could not then imagine.

All told, my father had four wives, the third of whom, my mother, Nosekeni Fanny, the daughter of Nkedama from the amaMpemvu clan of the Xhosa, belonged to the Right Hand House. Each of these wives — the Great Wife, the Right Hand wife (my mother), the Left Hand wife, and the wife of the Iqadi or support house — had her own kraal. A kraal was a homestead and usually included a simple fenced-in enclosure for animals, fields for growing crops, and one or more thatched huts. The kraals of my father’s wives were separated by many miles and he commuted among them. In these travels, my father sired thirteen children in all, four boys and nine girls. I am the eldest child of the Right Hand House, and the youngest of my father’s four sons. I have three sisters, Baliwe, who was the oldest girl, Notancu, and Makhutswana. Although the eldest of my father’s sons was Mlahlwa, my father’s heir as chief was Daligqili, the son of the Great House, who died in the early 1930s. All of his sons, with the exception of myself, are now deceased, and each was my senior not only in age but in status.

When I was not much more than a newborn child, my father was involved in a dispute that deprived him of his chieftainship at Mvezo and revealed a strain in his character I believe he passed on to his son. I maintain that nurture, rather than nature, is the primary molder of personality, but my father possessed a proud rebelliousness, a stubborn sense of fairness, that I recognize in myself. As a chief — or headman, as it was often known among the whites — my father was compelled to account for his stewardship not only to the Thembu king but to the local magistrate. One day one of my father’s subjects lodged a complaint against him involving an ox that had strayed from its owner. The magistrate accordingly sent a message ordering my father to appear before him. When my father received the summons, he sent back the following reply: “Andizi, ndisaqula” (I will not come, I am still girding for battle). One did not defy magistrates in those days. Such behavior would be regarded as the height of insolence — and in this case it was.

My father’s response bespoke his belief that the magistrate had no legitimate power over him. When it came to tribal matters, he was guided not by the laws of the king of England, but by Thembu custom. This defiance was not a fit of pique, but a matter of principle. He was asserting his traditional prerogative as a chief and was challenging the authority of the magistrate.

When the magistrate received my father’s response, he promptly charged him with insubordination. There was no inquiry or investigation; that was reserved for white civil servants. The magistrate simply deposed my father, thus ending the Mandela family chieftainship.

I was unaware of these events at the time, but I was not unaffected. My father, who was a wealthy nobleman by the standards of his time, lost both his fortune and his title. He was deprived of most of his herd and land, and the revenue that came with them. Because of our straitened circumstances, my mother moved to Qunu, a slightly larger village north of Mvezo, where she would have the support of friends and relations. We lived in a less grand style in Qunu, but it was in that village near Umtata that I spent the happiest years of my boyhood and whence I trace my earliest memories.

2

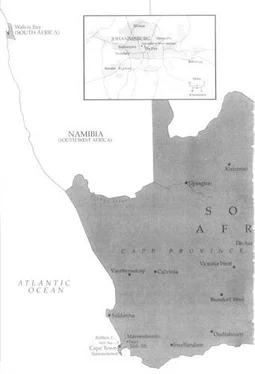

THE VILLAGE OF QUNU was situated in a narrow, grassy valley crisscrossed by clear streams, and overlooked by green hills. It consisted of no more than a few hundred people who lived in huts, which were beehive-shaped structures of mud walls, with a wooden pole in the center holding up a peaked, grass roof. The floor was made of crushed ant-heap, the hard dome of excavated earth above an ant colony, and was kept smooth by smearing it regularly with fresh cow dung. The smoke from the hearth escaped through the roof, and the only opening was a low doorway one had to stoop to walk through. The huts were generally grouped together in a residential area that was some distance away from the maize fields. There were no roads, only paths through the grass worn away by barefooted boys and women. The women and children of the village wore blankets dyed in ocher; only the few Christians in the village wore Western-style clothing. Cattle, sheep, goats, and horses grazed together in common pastures. The land around Qunu was mostly treeless except for a cluster of poplars on a hill overlooking the village. The land itself was owned by the state. With very few exceptions, Africans at the time did not enjoy private title to land in South Africa but were tenants paying rent annually to the government. In the area, there were two small primary schools, a general store, and a dipping tank to rid the cattle of ticks and diseases.

Maize (what we called mealies and people in the West call corn), sorghum, beans, and pumpkins formed the largest portion of our diet, not because of any inherent preference for these foods, but because the people could not afford anything richer. The wealthier families in our village supplemented their diets with tea, coffee, and sugar, but for most people in Qunu these were exotic luxuries far beyond their means. The water used for farming, cooking, and washing had to be fetched in buckets from streams and springs. This was women’s work, and indeed, Qunu was a village of women and children: most of the men spent the greater part of the year working on remote farms or in the mines along the Reef, the great ridge of gold-bearing rock and shale that forms the southern boundary of Johannesburg. They returned perhaps twice a year, mainly to plow their fields. The hoeing, weeding, and harvesting were left to the women and children. Few if any of the people in the village knew how to read or write, and the concept of education was still a foreign one to many.

My mother presided over three huts at Qunu which, as I remember, were always filled with the babies and children of my relations. In fact, I hardly recall any occasion as a child when I was alone. In African culture, the sons and daughters of one’s aunts or uncles are considered brothers and sisters, not cousins. We do not make the same distinctions among relations practiced by whites. We have no half brothers or half sisters. My mother’s sister is my mother; my uncle’s son is my brother; my brother’s child is my son, my daughter.

Of my mother’s three huts, one was used for cooking, one for sleeping, and one for storage. In the hut in which we slept, there was no furniture in the Western sense. We slept on mats and sat on the ground. I did not discover pillows until I went to Mqhekezweni. My mother cooked food in a three-legged iron pot over an open fire in the center of the hut or outside. Everything we ate we grew and made ourselves. My mother planted and harvested her own mealies. Mealies were harvested from the field when they were hard and dry. They were stored in sacks or pits dug in the ground. When preparing the mealies, the women used different methods. They could grind the kernels between two stones to make bread, or boil the mealies first, producing umphothulo (mealie flour eaten with sour milk) or umngqusho (samp, sometimes plain or mixed with beans). Unlike mealies, which were sometimes in short supply, milk from our cows and goats was always plentiful.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Long Walk to Freedom»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Long Walk to Freedom» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Long Walk to Freedom» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.