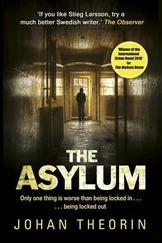

John Harwood - The Asylum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Harwood - The Asylum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Asylum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9780544003293

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Asylum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Asylum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Asylum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Asylum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was shaken to realise how long it had been since I had embraced anyone, and how much I had missed that intimacy. I remained kneeling before Lucia’s chair, with her head resting upon my shoulder and her cheek against mine until she disengaged herself—reluctantly, I felt—and sat up again. We both began to apologise at once; she for being so affected and I for distressing her, each reassuring the other until she confessed that she had eaten nothing all day except a square of toast and a cup of tea at breakfast.

“But where are you living?” I asked.

“In a temperance hotel in Marylebone. I have only a hundred a year, apart from a little capital, but I am determined to stay in England. My clothes are an extravagance, I know, but I must be well turned out; as I have no friends, no family, and no one to recommend me. I think I must go on the stage, but I wanted to see something of London first.”

“I should very much like to be your friend,” I said. “And I shall certainly not let you starve; you must come upstairs with me and have something to eat, and then I will show you Rosina Wentworth’s letters.”

She looked up at me, startled.

“But how can you have her letters, when you lost everything with your house?”

“My mother left them—and some other papers I am not allowed to see—with our solicitor; I shall tell you all about it in a moment.”

I closed the shop without a second thought and drew her to her feet, relieved to see the colour stealing back into her face.

After she had eaten—she wanted only tea and bread and butter, and did not seem very hungry, in spite of her fast—we went on up to my own small sitting room, where I told her about my mother’s perplexing bequest, and sat beside her on the sofa whilst she read through the letters with rapt attention. Pale sunlight slanted through the dusty pane, heightening the rich colours of her gown and sending tiny sparks through her hair, which she wore pinned up in a fashion very like my own. After she had finished, she was silent for some time, turning the letters in her hands as if she could not quite believe she was holding them.

“It is strange,” she said at last, “but I feel as if I know her already. Mama loved the piano, too, and she would play, very beautifully, whenever there was an instrument . . .”

We looked at each other, and I saw my own presentiment mirrored in her face.

“Lucia—may I ask how old you are?”

“Twenty-one.”

“And when is your birthday?”

“The—the fourteenth of February.”

“Just a month before mine—and a little more than nine months after Rosina’s last letter. And your mother loved the piano, and would never talk about her past.”

The papers rattled in her grasp; she set them aside and turned to me slowly, like someone waking from a dream.

“It explains everything,” she said. “Why we could never stay . . . why Mama never told anyone where we were going next . . . why I was drawn to you, here, today. It is fate, as you said . . . That is what the grey-faced man meant, that day in the garden: he had kept her secret, but someone had found out that Rosina Wentworth was in Rouen . . . and so we fled the very next day.”

Her hands trembled in her lap; a hectic spot of colour appeared on her cheek.

“Of course it means that I am a . . . that Mama was not married when she . . .”

“We don’t know that,” I said, placing my hand on hers, which were icy cold. “Perhaps Felix Mordaunt did marry her, and then—something happened to him.”

“No, I am certain he seduced and abandoned her, just as the maid Lily feared he would. Mama always warned me: ‘When you are in love,’ she would say, ‘you must never trust your heart, only your head. A man will say anything, promise anything—and mean it quite sincerely—to seduce you, but once you have given yourself, the chase is over: he will cast you aside without a backward glance.’ I knew she spoke from bitter experience, though she would never admit it.”

“Even if you are right,” I said, “your father—Jules Ardent, I mean—took pity upon her. You are his child according to law,” I added, wishing I felt more confident than I sounded.

“Perhaps there never was a Jules Ardent. Would an elderly Frenchman really have married a penniless English girl, disowned by her father, who was bearing another man’s child? I think Mama invented him for the sake of respectability.”

“What did your mother call herself?” I asked. “I mean, her Christian name?”

“She called herself Madeleine.”

“And—when was her birthday?”

“The twenty-seventh of July—she never told me her age. When I was small, I often thought how young and beautiful she looked. But then the lines crept over her face, and year by year she grew thinner . . . Of course, it was fear that aged her . . .”

“And—what did she die of?”

“Her heart gave out—just like your own mother’s. We were climbing the stairs in a pension—last December, it was, in Paris—she gave a little cough, and then a sigh, and her knees gave way. I caught her, thinking it was a faint, but she died in my arms.”

“I am so sorry,” I said, chafing her cold hands. “How strange, that our mothers should both . . . not so strange, perhaps, if they were cousins . . . though of course we cannot be sure.”

I had a momentary pang of doubt: was this no more than an extraordinary coincidence? If Rosina had become Madeleine Ardent, surely she would have gone on writing to my mother? But perhaps she had; perhaps those were the letters Mr. Wetherell was keeping from me.

“I am already sure,” said Lucia, regarding me with luminous eyes. Perched on the sofa beside me, she looked like some exotic bird of paradise come to earth. “It is blood that tells. You and I, we look alike, we think alike; already I feel I have always known you.”

“And I also,” I said, embracing her. “If only those letters had come to me while Rosina—your mother—was still alive; I should so love to have met her—and to have known you sooner.”

“I wish you had, too. But even if Mama had seen your advertisement, she would not have replied.”

“No, I suppose not—for fear of her father,” I said. Lucia shook her head in seeming bewilderment; she was studying Rosina’s letters again. A horrid realisation struck me.

“If he is still alive, he may have seen my advertisement, too. You may be in danger because of me.”

She looked up from the page and smiled, a little wanly.

“If you had not advertised, Georgina, we should never have met. As for Thomas Wentworth, he would be an old man by now, and surely—”

“Lucia . . . why did you call him Thomas Wentworth?”

She started, and glanced at me fearfully. “I must have read it here.”

“I am sure she never mentions his Christian name.”

We went through the letters again, line by line, without finding it.

“Lucia,” I said, “you see what this means. You must have overheard your mother—or someone—speaking of him. Just as Rosina’s name came to me.” Our shoulders were touching; I could feel a faint, continuous vibration thrilling through her body.

“Of course you must be right. The grey-faced man, perhaps . . .”

“Did you ever see him again?”

“No, never.”

“He, at least, was your friend. Did Rosina—your mother—not leave you any letters or papers?”

“Nothing. She received very few letters—few, at least, that I saw—and those she burned as soon as she had read them. All she had were her clothes, her articles de toilette —I have forgotten the English word—a few necessities—everything she owned would fit into one small trunk, and she brought me up to do the same. ‘Possessions are a snare and a burden,’ she used to say. ‘They only weigh us down. The fewer things we have to carry, the freer we are.’”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Asylum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Asylum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Asylum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)