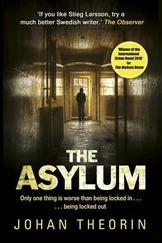

John Harwood - The Asylum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Harwood - The Asylum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Asylum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9780544003293

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Asylum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Asylum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Asylum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Asylum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“There will be no expense, Uncle; Lucia will contribute fifteen shillings a week, just as I do, which is more than enough to pay for her keep.”

The last part, at least, was true; I had resolved to pay him myself, without telling her. It would leave me less than ten shillings a week, but I did not care.

“And there will be no inconvenience, either; Lucia will help in the shop, when she can, and we will take our meals upstairs in my sitting room, so that you can read at table in peace, without being disturbed by our chatter.”

“Well—I shall think about it,” he said, folding his catalogue.

“No, Uncle, we must decide now. She is staying in a hotel, and she needs a home.”

“Mrs. Eddowes will not like it—she will complain.”

“I will deal with Mrs. Eddowes,” I said, realising to my surprise that I meant it.

“But, but—we know nothing about Miss Ardent.”

“I know already that she is my dearest friend,” I said firmly. “She and I have a great deal in common.”

“No, no, no; I really cannot allow it. The inconvenience has already begun; I was very surprised, Georgina, to find the shop closed when I returned from yesterday’s sale. If you are going to be gadding about with Miss Ardent when you should be minding the shop . . . and now I must get on.”

“Uncle,” I said breathlessly, “if you will not allow Lucia to stay, then I must leave your house. I shall always be grateful to you for taking me in, but I have been very unhappy, and desperately lonely here, and without Lucia’s company, I can bear it no longer.”

He sank back into his chair, with one hand pressed against his heart.

“But, Georgina, what has possessed you? I had no idea you were unhappy. If you wished to take an afternoon off, you had only to say so. How will I manage without you? The orders . . . the parcels! How will I ever get out to a sale?”

He looked and sounded so feeble that I feared he might collapse on the spot. If he does, I thought, I will be wholly to blame: I encouraged him to dismiss the boy, and I insisted upon helping in the shop; of course he has grown to depend upon me. But the thought of Lucia spurred me onward.

“You managed perfectly well before, Uncle. We can easily find you someone else to do the parcels and mind the shop.”

“But he would want to be paid! I cannot afford the expense!”

“In that case, Uncle, you have only to agree that Lucia may live with us.”

“Oh very well, very well, if you insist. But it is really most . . . most inconvenient.”

“You will not be inconvenienced in the slightest, Uncle. Everything will be exactly the same.”

“I do not see how, but I suppose I must put up with it.”

He rose unsteadily to his feet and shuffled out of the room, leaving me shaken by my own boldness and wondering if I had grown callous and hard-hearted.

Thursday, 12 October

It is after midnight. Lucia is (or so I imagine) asleep in her room, which is already quite transformed; it is such a delight to have her here, and I know that she shares my feeling. Such a contrast to yesterday: Uncle was wounded and huffish all morning; then, as the afternoon dragged on and still Lucia did not return, I paced about the empty shop like a caged animal, imagining all sorts of catastrophes.

When at last she appeared in the doorway, I confess I shed tears of joy, and then felt very ashamed of myself: she had woken very early and did not want to disturb me. She had been walking and thinking all day, she said, reliving her life as if it were someone else’s. Charlotte and I had aired her room and made up the bed, but she chose to spend one more night in the hotel, “to prove to myself that I am not afraid to be alone,” she said, “now that I know I don’t have to be.” I spent the evening composing a letter to Mr. Lovell, and tossed and turned most of the night . . . but she is here now, and safe, and that is all that matters.

Wednesday, 18 October

It is only a week since Lucia appeared in the shop, and already I cannot imagine life without her. The likeness astonishes me more every day. Uncle cannot tell us apart, and nor, I think, can Mrs. Eddowes; not that she would care. Lucia wears my clothes, having so few of her own apart from the gorgeous peacock gown; she is having two new dresses made in the same pattern as my own. When I teased her about it, she smiled and said, “Yes, I am a chameleon; I take on the colour of my surroundings.” We often wonder whether our mothers resembled each other as closely as we do, but without so much as a miniature between us, we can only speculate. Lucia is always constrained when she talks of “Mama”—the mother she remembers—whereas she will speculate freely about “Rosina,” as if they were quite separate beings. She finds my childhood inexhaustibly fascinating, and steers the conversation back to me at every opportunity. Mr. Lovell has not yet replied, so we have nothing more to go upon.

Uncle is still being huffish and put upon with me (or with Lucia, when he confuses us—she takes it in very good part). I should never have promised him that everything would stay the same. He sighs ostentatiously at the smallest change to his routine, and reminds me at least twice a day that he is far too old to manage without me. I had selfishly imagined that Lucia and I would look after the shop together, but she prefers to walk alone in the afternoons. She is very tactful about it, but I can tell that she craves solitude in which to reflect. “It is like remembering two different lives at once,” she said yesterday, “and wondering which of them is mine,” but she will not be drawn beyond generalities.

I worry about her wandering the city alone, with very little idea of where her feet are carrying her; she insists that she is not afraid of Thomas Wentworth—or anybody—but is she simply putting on a brave show for my sake? I cannot tell. I suspect she broods, as I would surely do in her place, over the dark strain in the Mordaunt blood, and whether it runs in her veins, but of course I dare not speak of that in case I am mistaken. Sometimes, when her face is shadowed, a chill comes over me, and I fear she would have been happier if we had never met.

I understand completely why she needs this time alone; yet I long to be of more comfort to her: I would happily spend every waking—and sleeping—minute beside her. Every smile, every caress, every kiss, is precious to me: friends and cousins in novels are always kissing and embracing, but every evening—the time I most look forward to—when we embrace and say good night, I long to say, Come to bed with me, and let me hold you as I did that first night.

On Sunday I summoned the courage to say, “Lucia, I know you suffer from nightmares; why don’t you stay with me, and then I can comfort you?” She smiled and caressed me, and seemed to hesitate before she replied, “Thank you, dearest cousin, but I’m sure I shall sleep soundly tonight.” I am afraid to ask her again, in case she should think—I am not even sure what. Is it wrong of me to feel as I do? Am I like Narcissus, falling in love with my own reflection?

Thursday, 19 October

Today, for once, Uncle Josiah did not go out; he was expecting one of his oldest clients, and said I might take the afternoon off. Lucia, to my delight, insisted that I accompany her. We walked up to Regent’s Park, arm in arm, and wandered around until we came upon a little grotto with a seat inside, just out of sight of the path. This, surely, was where Rosina and Felix Mordaunt had sat and talked. There was even a coffee stall nearby, kept by a wizened old man who said he had been there twenty-seven years, perhaps the very same one; it was like being served by a ghost.

We took our tea back to the grotto and sat down on the bench, which was only just wide enough for two. Our shoulders were touching; I took my cup in my left hand so as not to jostle Lucia, and edged a little closer to her, until it came to me that this was how Rosina must have felt, sitting in this exact spot, with Felix Mordaunt beside her.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Asylum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Asylum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Asylum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)