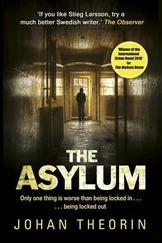

John Harwood - The Asylum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Harwood - The Asylum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Asylum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9780544003293

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Asylum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Asylum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Asylum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Asylum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On a wintry afternoon, she seemed to rally. She had slept most of the day, and, on waking, asked for an infusion and had me arrange her pillows so that she was sitting upright. Her hand felt very cold in mine, as it always did now, no matter how assiduously we kept up the fire.

“I think you should go to your uncle,” she said.

“But you would hate London, Aunt; you’ve always said so.”

“I meant, when I am gone.”

“You are going to get better,” I said firmly, “and then we shall find another cottage—not so close to the cliff this time—and live as we always have.”

“No, my dear, I’m not getting better. No tears now, child; I’ve had a good life, and I count myself lucky to have spent these last years with you.”

“Please, Aunt, you musn’t—”

“Pay attention, child,” she said, with a flash of her old self. “Things you need to know. I wrote it all down, but that’s at the bottom of the cliff now.”

I dabbed at my eyes and tried to compose myself.

“I’ve provided for the servants, of course. You’ll have about a hundred a year. Sorry it’s not more, but half our income dies with me because I never married. And there’s about two hundred capital, in trust from your mother. The cottage was to be yours, and everything in it—no use now. If you go to Josiah, you’ll be able to save a bit. Maybe find an occupation—we’ve talked of it often enough—more chance for you in London.

“Our solicitor’s name is Wetherell—Charles Wetherell, in George Street, Plymouth. When I’m gone, write to him. I’ve named Josiah as your guardian—has to be someone—told him to let you do as you please.

“Now—marriage. You know what I think, but you’re a handsome gel, not like I was. You’ll have offers. If you accept someone, write to Mr. Wetherell—tell him who you’re marrying. Papers to draw up—he’ll tell you what’s needed.”

She slid back amongst the pillows, breathing hard, and closed her eyes. I could not bring myself to disturb her, and three days later she was dead.

I arrived at Gresham’s Yard in the midst of a fog that would last another three weeks. I was used to the gentle mists that drifted about our house on the cliffs, and I had vaguely assumed that fog was the same, only denser. But this was altogether different: noxious, laden with soot, a dark, greasy yellow by day, pitch-black by night, clutching at the throat and choking the lungs. My uncle cheerfully informed me that this was nothing compared to the fog of two winters before, which had begun in November and lasted until the following March. And even when it lifted, the streets remained shrouded, either in smoke or driving rain: I woke each morning feeling as if I had inhaled a lungful of coal dust, and I was always catching cold.

My spirits, desolate enough when I arrived, sank lower as the weeks dragged on. My uncle was interested only in bookselling, and since his specialty was obscure theological works, there was little to converse about. To any question about our family, his invariable reply was, “You know, Georgina, it was such a long time ago; I really can’t recall,” until I gave up asking. What I had taken for benign approval was really benign indifference, an absolute lack of interest in anything beyond the confines of his shop.

As the days lengthened, and I began to venture out of doors, I discovered that everything sounded louder, and smelt worse, than I had ever imagined; my nostrils were constantly assailed by the stench of dung and drains, decaying meat and rotting fish, my ears deafened by the clatter of hooves and the cries of street vendors; yet the sheer extremity of sensation was a relief from the oppression of the house. In my wanderings through Bloomsbury, I was constantly amazed at how quickly the scene could change, from the grand houses in Bedford Square to wretched tenements a mere hundred paces away. The first time I saw a man sprawled dead drunk in the gutter, with passersby taking no more notice of him than of a sack of coals—far less, indeed, for the coals would have been carried off at once—I wondered if it was my duty to help him. But I soon learnt to avoid meeting the eyes of my fellow pedestrians, to walk briskly through the less-salubrious streets, and which streets to avoid altogether.

Gresham’s Yard was a small, cobbled square, opening onto Duke Street, close by the Museum. A little sign above the entrance said JOSIAH RADFORD: ANTIQUARIAN BOOKS BOUGHT AND SOLD. There were other shops in the square, including a stationer, a cabinetmaker, a tailor and a haberdasher. You passed through the entrance, which was like a short tunnel of blackened stone, roofed over by the upper floors of the houses, turned left, and there was the entrance to the bookshop, where my uncle sat in the front room at a battered roll-top desk when he was not pottering with the stock.

Despite his shortsightedness, he seemed to know where any book was in the shop, and if the price was not pencilled on the flyleaf, he would always give it without hesitation. The customers were mostly elderly men like my uncle, scholars who worked at the Museum. The whole of the ground floor, a warren of small rooms on several different levels, was crammed with books; shelves extended from floor to ceiling on every available wall. The rooms, some of them windowless, were lit by gaslights in chimneys, and heated by two stoves at the front and back. My uncle was mortally afraid of fire, and would not allow a naked flame anywhere in the house. He was also, I discovered, mortally afraid of spending money on anything other than books. I gave him fifteen shillings a week for my keep, which was certainly more than it cost him, and took over the duties of the boy who had helped him with the parcels in the mornings, but he still blanched at the smallest expense.

Beside the entrance to the bookshop was the area, protected by iron railings, with steps going down to the kitchen and scullery. Beyond that was the house door, opening onto a flight of stairs that ran straight up to the first floor, where my uncle had his quarters overlooking Duke Street. Here also was the dining room, served by a dumbwaiter and another narrower staircase leading down to the servants’ quarters. Mrs. Eddowes, the housekeeper, was a gaunt, elderly woman with steel-grey hair who kept very aloof, in the manner of one who was doing my uncle a great favour by remaining, though she had been with him a decade or more. She had seven dishes, one for each day of the week, with which my uncle seemed entirely content. There was a washerwoman who came in, and the maid, Cora, of whom I saw very little—the latest in a series of maids, I gathered, though Uncle Josiah did not seem to notice the difference. My uncle did not like servants waiting at table, and had everything sent up in the dumbwaiter. I preferred to clear away myself and to send the dishes down to be washed, which I am sure suited Cora very well.

On the next floor up were a bedroom and bathroom, and above that two more bedrooms on the third floor. I chose the westward-facing one of these for my sitting room, because of the view over the rooftops; when the air was clear enough, you could catch glimpses of the river. It was barely ten feet square, with a small grate; a Persian rug so faded you could scarcely see the pattern; a tattered old chaise longue, which I draped with velvet; a small round table; and two upright chairs. I repapered the walls myself, in a green leafy pattern, which sometimes caught the afternoon light, and placed the sofa beneath the window. There I spent much of that interminable winter, desultorily reading novels and yearning for a friend. But where was I to find one? As the weather improved, I took to visiting the Museum and various galleries, and I would sometimes smile tentatively at other women, but they were almost never unaccompanied; at best they might smile faintly in return, and then move on.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Asylum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Asylum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Asylum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)