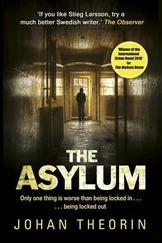

John Harwood - The Asylum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Harwood - The Asylum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Asylum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9780544003293

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Asylum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Asylum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Asylum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Asylum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I can’t. I’ll never find the way.”

“S’pose not,” she said after a pause. “But if the sky clears, go at once.”

Even halfway up the path—as surely we must be?—the roar of the sea was terrifying. The time could not be much past nine o’clock; nearly ten hours until the dawn, unless the clouds parted. The moon had been full a week ago, before the rain began, but even starlight would be enough to guide us. We were both shivering now, and I could not feel my feet. I wrapped my arms still more tightly around my aunt and waited for the end, trying not to imagine the ground opening beneath us, the bone-crushing fall, being buried under tons of rock and yet still conscious—and recalled, with terrible clarity, a torrent of earth and rock plummeting down the cliff, and my being suspended in midair by a tangle of roots, with red dirt spilling over me.

“Rosina! Help me!” I heard myself cry.

My aunt gave a violent start and twisted in my arms.

“What? What did you say?”

“It was—only a sort of prayer.”

She muttered something I did not catch, and subsided. I remembered my mother finding me at the mirror, and the fear in her voice when she asked me about Rosina. If we lived, I thought, I would make Aunt Vida tell me—whatever there was to tell, about Rosina, and Nettleford, and my father . . .

But still the rain beat down, and the wind whipped about us in the darkness, carrying away what little warmth remained in my body. The shivering increased until I had to clench my teeth against it. It would be the worst of ironies, I thought, if we were found frozen to death with the house still standing. I had read somewhere that shivering was the body’s way of keeping itself warm, and I began hugging my aunt rhythmically, hoping to squeeze some warmth into her. Mud squelched beneath us; I kept feeling that we were toppling to one side or the other, with only the pressure of the gorse against my back to tell me it was an illusion. Pinpoints of coloured light drifted before my eyes; for a wild moment I thought they were stars, until I realised that my eyes were tightly shut; the pinpoints were still there when I opened them. I clung to my aunt, and shook, and prayed for rescue.

Her head lolled against my cheek, lurched away, and lolled again. The rain had lessened; even the roar of the waves had receded. I realised that I was no longer shivering. My arms and legs were numb, but that did not seem to matter, as I did not feel cold anymore, only pleasantly drowsy, as if I were sinking into a warm bath . . .

I was lying in soft grass, beside a hedgerow crowded with blossom, the colours richer and more dazzling than anything I had seen: reds and crimsons and violets and pinks and whites so breathtaking I could feel them softly vibrating. Sunlight warmed my cheek; the air quivered with the chirruping of birds and the deep, resonant hum of bees, growing louder and louder until my body shook to the sound. Then the sun vanished with a colossal roar, and I was plunged back into freezing darkness, with the long, booming echoes of another landslide reverberating in the darkness below.

“’S the end,” my aunt mumbled. “Mus’ leave me.”

“Aunt, you must wake up,” I said. “We’ll die if we go to sleep again.”

I began squeezing her once more, with arms I could not feel, assuring her that we had slept most of the night away—and wishing I believed it myself—but she only stirred, and muttered something unintelligible. The rain, at least, had stopped, but the wind still swirled around us, and the sea, now that I was fully awake, sounded even louder and closer than before.

How much more of the cliff had gone? Had it taken the house this time? As I strained my eyes toward the crashing of the waves, it seemed to me that the darkness was no longer impenetrable. Looking up, I caught a glimpse of stars, blurred by a flying skein of cloud. Faint outlines of bracken coalesced around me. To see if the house was still there, I would have to stand, but my legs refused to obey me; for all the feeling in them, they might have been amputated.

What should I do? If the starlight held, and I could make my legs move, and climb the path, I could reach Niton in twenty minutes, and my aunt would be rescued within the hour. If I stayed, she would survive the cold longer—but not until morning, which I felt certain was still many hours away, even if a third landslide did not claim us.

As gently as I could, I withdrew my arm from around her, took one of my lifeless legs in both numb hands, and began to work at it, pushing and pulling until a spasm of cramp seized my calf. I did the same to the other, clutched at the gorse for support, and dragged myself slowly upright.

A pale gleam, low in the sky, appeared from behind a cloud. It was the moon, only just risen—so the time could not be much past midnight—above a seething chaos of foam. Where the silhouette of our house should have been, no more than fifty yards down the slope, there was only an uneven line of darkness, stark against the white of the sea.

Numb with dread as much as cold, I turned to face the climb. Pain shot through an ankle; my foot, I realised, must be trapped in the mud. As I tried to free it, the moon was blotted out, and I was plunged once more into absolute darkness.

No, not absolute. A star—a bright yellow star—shone out above me. And no, not a star but a lantern, swaying as it descended, and voices calling our names.

Though I escaped with only a severe head cold and a lingering chill in my bones, my aunt was stricken with fever. She lay delirious for several days, hovering between life and death, and by the time the fever broke, her lungs had been gravely weakened. We had been taken to the vicarage, where we remained in adjoining rooms, tended by Amy and Mrs. Briggs, whom Mr. Allardyce had kindly allowed to join us.

If the cottage had been spared, I think my aunt might have regained her health. I had somehow assumed, from her muttered words on the path that night, that she knew it had gone. But the first thing she said to me after the fever had subsided was “When can we go home?” and all I could bear to reply was, “Not yet, Aunt; you must get stronger first.”

I walked round to the headland later that morning and stood for a while in pale sunlight, looking down from the top of the path. Our rescuers’ trampled footprints were still clearly visible around the place where my aunt and I had waited. Fifty yards farther down, the path ran straight over what was now the edge of the cliff. The rubble was completely hidden from view; of the house and garden, nothing remained but empty air, and the wash and slide of the sea below. Everything we possessed—our clothes, our books, our furniture, my mother’s jewel box, the trunk containing her own belongings—everything but my brooch and writing case lay buried under hundreds of tons of earth. I wondered how long I could put off telling my aunt, but someone must have let it slip, for when I returned from an errand a few hours later, she took my hand and said quietly, “It’s all right, my dear; I know.”

From that day onward, she ceased to struggle. The Aunt Vida of old would have been up and dressed the minute she could stand, waving away objections and declaring that all she needed was a good walk. But now she seemed content to lie propped up on a litter of pillows and watch the last of the autumn leaves drifting to earth. Our windows faced inland, but she showed no interest in what the sea was doing; nor did she ever ask me to describe the scene where the cottage had stood.

Her awkwardness about being touched had gone, too. She no longer withdrew her hand from mine, or held herself rigid when I put my arm around her, but simply accepted my embrace. Even Mr. Allardyce, himself now very old and frail, would hold her hand when he sat with her. We kept up the pretence that she was convalescing, but as the days passed, her breathing became more laboured, and when she slept, I could hear a faint, bubbling undertone. Fluid on the lungs, the doctor said; there was nothing to be done but keep her warm and comfortable and hope for the best.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Asylum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Asylum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Asylum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)