When her mother could no longer afford the allowance, John Blofeld suddenly wrote saying that he and his friend, a Thai princess called Mom Smoe, had decided they both wanted to support her.

‘I wrote back thanking him and saying I could live on half the amount he was suggesting. He replied that if he took a Thai farmer out to a 10-baht meal it would seem an enormous amount to the farmer but little to him and that likewise I should accept. When Mom Smoe died John took over her share until his own death. He used to put the money, about £50 a year, into a bank account and I would take it out when I needed it. His donations were extremely helpful when I was living at Tayul Gompa and not going out and meeting anybody to give me donations,’ she said.

Still, £5 or less a month is little to live on, even in India. Sometimes there was not even that. It taught her, the hard way, the fundamental principle of being non-attached to the material, and the rare lesson of trust: ’There have been times when I have had no money, not even for a cup of tea. I can remember one time in Dalhousie when I didn’t have anything left. Not a single rupee. I had nowhere to live, and nothing to buy food with. I stood on the top of a hill with waves of isolation and insecurity running over me. And then I thought, if you really take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha (the monastic community), as we all do at our ordination, and sincerely practise, then you really shouldn’t be concerned. Since that time I have stopped worrying,’ she said nonchalantly.

‘I have learnt not to be scared. It’s not important. The money appears from somewhere, usually the exact amount I need, and nothing more. For example, one time I needed £80 for a train fare to visit friends. I had arrived with just £10 in my purse. On the day I was leaving the woman I was staying with handed me an envelope with a donation of just £80 in it. I thanked her and laughed. It was such a strange amount to give, but precisely what I required. So it’s like that.

‘Actually, as ordained Buddhists we shouldn’t care about money – be it big or small,’ she went on. ‘I always travel third class in Asia and sleep on the floor of pilgrims’ rest houses, but I’m not adverse to travelling first class and staying in beautiful places if they’re offered. We also have to learn not to be attached to simplicity and poverty. Wherever one is one should feel at home and at ease, be it an old chai shop or a five star hotel. The Buddha was entertained by kings and lepers. It was all the same to him. And Milarepa said, “I live in caves for the practitioners of the future. For me, at this stage, it’s irrelevant."’

But for the Englishwoman wanting to get out of London and back to Lahoul money was definitely needed. True to form, her faithful friend and sponsor John Blofeld offered her a plane ticket but this time Tenzin Palmo refused. Her principles wouldn’t allow it. ‘I said I could not possibly accept donations as I had not been doing any dharma activity in the West to earn them,’ she said crisply.

There was nothing for it but to get a job. So, dressed in her robes, with her severely short hair-do, Tenzin Palmo fronted up to the Department of Employment to ask for work. Unfazed by her unorthodox appearance, or perhaps intrigued by it, they listened to her curriculum vitae (librarian skills, office work, teaching experience) and promptly hired her themselves. She was just the person they were looking for to set up panels of different professionals to interview applicants for vocational training. In spite of being out of the workforce for ten years, Tenzin Palmo was so efficient at her job they begged her to stay on to co-ordinate the whole project.

She politely but hastily declined. If ever she had any doubts about her vocation, her two and a half months at the Department of Employment soon banished them. ‘I felt very sad. There were all these middle-aged guys saying, “What have I done with my life?" and young married people with mortgages, already trapped. All they talked about was what was on TV. I was in my robes and because of that they opened up. They told me about their lives and used to ask me all sorts of questions they were very interested in my way of life and what it meant,’she said.

Her appearance, still extremely unusual in the early seventies, in fact drew people to her everywhere. They were fascinated by the phenomenon of an English Buddhist nun and hungry for the values that she had embraced. More than once she was approached in social gatherings and told she looked like St Francis of Assisi. One well-dressed man stopped her in Hyde Park and told her she looked so chic that she must be French. There was also the time when she was travelling by train to Wales to visit her brother who was living there and she was joined by two policemen, a detective inspector and a sergeant. Conversation started up and they explained that they were on their way to arrest a man in a Welsh village for murder.

‘Can you tell me anything that will help me make sense of my life?’ asked the Inspector, obviously depressed by his mission.

Tenzin Palmo answered by telling him about karma, the law which decrees that every action of body, speech and mind, when accompanied by intention, brings about a correlating reaction. In short, she said, we are all ultimately responsible for our lives and as such can actively influence the future. It was a long lucid discourse and the policemen listened attentively. When it was over the Inspector leaned across and said in appreciation: ‘I think it is the custom to make offerings to Buddhist monks and nuns,’ and handed her £5. The sergeant did likewise. These were gratefully added to her escape fund.

Finally she had earned enough money and was off, back to her beloved India. En route she stopped over in Thailand to visit John Blofeld, who attempted once again to give her a donation. ’Since you are too proud to take my offerings for secular purposes, here is some money for you to go to Hong Kong to take the Bhikshuni ordination,’ he said.

This was an offer she couldn’t refuse. The Bhikshuni ordination meant nothing less than official and full admittance into the Buddhist order with all the authority and prestige that that entailed. It was a gem all Buddhist nuns yearned for, and few ever received. For complicated reasons steeped in tradition and the patriarchy, no Buddhist country other than China allowed their nuns the honour and respect of full ordination, thereby relegating them to inferior standing in the community. And since few nuns had the money or means to travel to Taiwan or Hong Kong (the only places it was available), that was where they stayed.

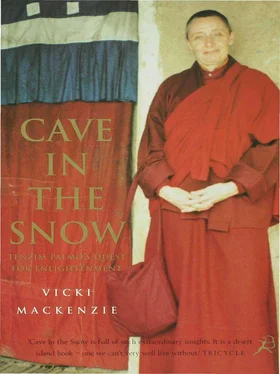

Arriving in Hong Kong, Tenzin Palmo duly donned the black and brown robes of the Chinese Buddhist nun and with head bowed and hands together stood through the long ceremonies which formally accepted her as a full member of the Buddhist monastic community. As she did so camera lights flashed and reporters scribbled furiously. Tenzin Palmo made the headlines. Once again she was the first Western woman to take such a step and the Chinese occupants of the former British colony were mesmerized. What the photographers did not pick up, however, were the little stumps of incense which, as part of the ritual, had been placed on the nuns’ heads and left to burn slowly down on to the freshly shaven scalps, leaving a small scar to remind them for ever of their commitment. Tenzin Palmo cried, but not from pain.

‘I was absolutely blissed out,’ she said. Later, when she showed a photograph of the event to H. H. Sakya Trizin, her second guru, he took one look at her white beatific face silhouetted against the black cloth and remarked: ‘You look like a bald-headed Virgin Mary.’

After all these delays and detours she finally reached Lahoul and resumed her way of life with renewed determination: getting in supplies during the summer weeks, strict meditational practice during the winter. Her mind and heart were still set on Enlightenment. But for all her enthusiasm, and the strength of her will, the conditions at Tayul Gompa for the sort of spiritual advancement that Tenzin Palmo was seeking were still far from satisfactory.

Читать дальше