Like all Tenzin Palmo’s desires to progress on the spiritual path, this one too was thwarted by opposition from the community. She continued to be given the most elementary of teachings. Finally, one day she cracked. She packed her bags and prepared to say farewell to Khamtrul Rinpoche, the man who had guided her for hundreds of years and whom in this life it had been so difficult to meet.

‘Leaving? You’re not leaving! Where do you think you’re going?’ Khamtrul Rinpoche exclaimed.

‘You’ll always be my lama in my heart but it seems that I have to go elsewhere to get the teachings – otherwise I could die and still not have received any dharma,’ she replied.

‘One thing I can assure you, you will not die before you have all the teachings you need,’ he promised, and organized for her to be taught by one of the of Togdens. It helped but not enough. The situation to her mind was still far from satisfactory. And then one day Khamtrul Rinpoche turned to her and announced: ‘Now it is time for you to go away and practise.’

Her probation was over. She looked at her guru and suggested Nepal. Khamtrul Rinpoche shook his head. ‘You go to Lahoul,’ he said, referring to the remote mountainous region in the very northernmost part of Himachal Pradesh, bordering on to Tibet. It was renowned for its meditators and Buddhist monasteries, especially those started by a disciple of the sixth Khamtrul Rinpoche, the yogi whom Tenzin Palmo had been close to in a previous life.

This time happily following her guru’s wishes, Tenzin Palmo packed up her few belongings and set off. A gompa (monastic community) had been found to accommodate her. It was 1970, she was twenty-seven years old, and another entirely new way of life lay in store.

Like all journeys taken with a spiritual goal in mind, the way into Lahoul was strewn with difficulties and dangers, as if such obstacles were deliberately set in place by the heavenly powers in order to test the resolve of the spiritual seeker. For one thing, the remote Himalayan valley was totally cut off from the rest of the world for eight months of the year by an impenetrable barrier of snow and ice. There were only a few short summer weeks when Tenzin Palmo could get through and she had to time it correctly. For another, the way into this secret land was guarded by the treacherous Rhotang Pass. At 3,978 metres, it had claimed many a life, rightly earning its name, ‘Plane of Corpses’. As if this was not enough, Tenzin Palmo had to make the journey on foot, for when she first went there Lahoul and its more inaccessible neighbour Spitti had not been discovered by the tourists and there were no nicely constructed roads carrying busloads of adventurers clutching their Lonely Planet Guides, no young men making romantic journeys on motorbikes, as there are today.

She began the climb before dawn. It was essential she cross the Rhotang before noon. After midday the notorious winds would rise, whipping up the snow that still remained at the very top even in the height of summer, blinding unwary travellers, disorientating them, causing them to lose their way. A night spent lost on the Rhotang meant exposure and inevitable death. Knowing this, the authorities insisted that before she set off Tenzin Palmo supply them with a letter absolving them of all responsibility should she meet her doom. She happily complied.

As she climbed she left far behind the lush, soft greenness of Manali, with its heavily laden orchards and chaotic bazaars full of its famous woven shawls. The picturesque town in the Kulu valley had been her last stop from Tashi Jong, and she had taken the opportunity to stay with an eminent lama, Apho Rinpoche (a descendant of the famous Sakya Shri from her own Drugpa Kargyu sect), in his small, charming monastery surrounded by roses and dahlias. He had welcomed her, impressed by the spiritual fervour of the Western nun, a sentiment which would be reinforced over the coming years as he and his family got to know her better. Now she headed for the Rhotang Pass, climbing beyond the treeline, the land growing more rugged and desolate with every step. Here and there she saw the occasional shaggy-haired yak, small herds of stocky wild horses, and in the distance a huge solitary vulture perched imperiously on a rock. At this altitude the slopes were no longer friendly and pine-covered but austere, jagged and bare, scarred by the heavy weight of near-perpetual snow and the run-off from the summer melt. Crossing her path were slow-moving glaciers, and ’streams’ of loose rock from recent landslides. Even in the height of summer the wind was icy. Undeterred, she continued climbing until she reached the pinnacle. Then, as if to reward her for her considerable effort, she was greeted by a remarkable sight.

‘At the top was this large piece of flat ground, about a mile long, with snow mountains all around. It was incredible. The sky was deep blue, flawless. I met a lama up there with his hand drum and human thigh bone, which he used as a ritual trumpet to remind him of death, and I walked along with him. We crossed the pass together and virtually slid all the way down the other side,’ she said.

When she got to the bottom she found she had entered another world. ‘It was like arriving in Shangri-la. I had gone from an Indian culture to a Tibetan one. The houses all had flat roofs, there were Buddhist monasteries dotted over the mountainsides, it was full of prayer wheels and stupas and the people had high cheekbones, almond-shaped eyes and spoke Tibetan,’ she recalled.

Tenzin Palmo had stumbled upon one of the oldest and most potent strongholds of Buddhism in the world. It had been in existence for centuries – first fed by the influx of refugees fleeing the Islamic invasion (which sacked the great monastic universities existing in India at that time) and then nourished by a constant stream of accomplished yogis from both neighbouring Ladakh and Tibet. Secreted away in these vast mountains and narrow valleys, Buddhism had flourished, spurred on by the efforts of the many mystical hermits who took to the caves in the area to practise in solitude. Over the years their spiritual prowess had grown to legendary proportions, so that, it was said, the very air of Lahoul was ionized with spirituality. And just setting foot on the soil there was guaranteed to shift any sincere spiritual aspirant into a higher gear.

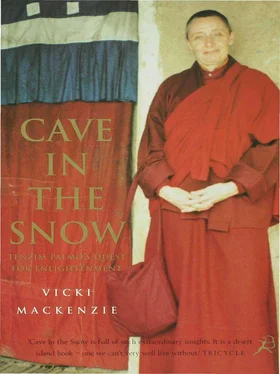

In 1970, when Tenzin Palmo got there, the Lahoulis had seen little of the outside world. They were a good-looking, simple people steeped in their faith, who spent their lives cultivating their potato and barley crops and tending their animals. Twentieth-century inventions such as electricity and television had yet to be seen, as had many white faces. Tenzin Palmo’s arrival, in maroon and gold Buddhist robes no less, caused flurries of excitement and distrust. What was such a strange-looking person doing there? How could a Westerner be a Buddhist nun? Rumour hurriedly went round that the only possible explanation was that she was a government spy! It was only when they witnessed the sincerity of her spiritual life and her complete dedication that they relaxed and accepted her as one of their own. She became known as ’Saab Chomo’(European nun), and after her long retreat in the cave was hailed as a saint.

Her destination was Tayul Gompa, meaning ‘chosen place’ in Tibetan. It was an impressive building some 300 years old, situated among the trees a few miles away from the capital, Keylong. It contained an excellent library, a fine collection of religious cloth paintings and a large statue of Padmasambhava, the powerful saint accredited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet. In many Buddhists’ eyes he was regarded as a Buddha. Now Tenzin Palmo’s living conditions improved. After years of moving from rented room to rented room she was finally given her own home, one of the small stone and mud houses on the hill behind the temple where all the individual monks and nuns lived. She liked the people of the district enormously and over the years befriended many of them, becoming especially close to one man, Tshering Dorje, whom she called ‘my Lahouli brother’. He was a big, craggy man of aristocratic descent, who came from one of Lahoul’s oldest and most famous families. He had made his name as a scholar, amassing a collection of fine books from all over the world, and later becoming a guide and friend to several trekking dignitaries including the publisher Rayner Unwin.

Читать дальше