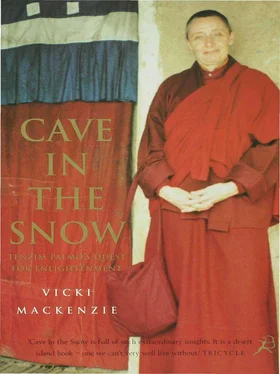

With the cave finished, Tenzin Palmo moved in and began her extraordinary way of life. She was thirty-three years old. This was to be her home until she was forty-five.

Her quest may have been purely spiritual but before she could get down to grappling with the immaterial she first had to conquer the eminently mundane business of simply staying alive. For the bookish, other-worldly and decidedly un-robust woman this was a challenge.

‘I was never practical. Now I had to learn to do umpteen physical things for myself. In the end I surprised even myself at how well I managed and how self-sufficient I became,’ she admitted.

The first priority was water.

‘Initially I had to get my water from the spring, which was about a quarter of a mile away. In summer I’d have to make several trips, carrying it to my cave in buckets on my back. In the winter, when I couldn’t get out, I melted snow. And if you’ve ever tried to melt snow you would know how difficult that is!A vast amount of snow only gives you a tiny amount of water. Fortunately in the winter you don’t need a lot because you’re not really washing either yourself or your clothes and so you can be very economical with the water you use. Later, when I did my three-year retreat, and could not venture beyond my boundary, someone paid for a water-pipe to be laid right into the cave’s compound. It was an enormous help,’ she explained.

Next was food.

There was of course nothing to eat on that sparse mountainside. No handy bushes bearing berries. No fruit trees. No pastures of rippling golden wheat. Instead she arranged for supplies to be brought up from the village in the summer, but as often as not they would not arrive and Tenzin Palmo would be reduced to running up and down the mountain herself carrying gigantic loads. ‘It took a lot of time and effort,’ she said. For the bigger task of stocking up for her three-year retreat Tshering Dorje was put in charge:

‘I would hire coolies and donkeys to carry up all that she needed,’ he recalled. ‘There would be kerosene, tsampa, rice, lentils flour, dried vegetables, ghee [clarified butter], cooking- oil, salt, soap, milk powder, tea, sugar, apples and the ingredients for ritual offerings such as sweets and incense. On top of that I employed wood-choppers to cut logs and these were carried up as well.’

To supplement these basic provisions with a source of fresh food Tenzin Palmo made a garden. Just below the ledge outside her cave she created two garden beds in which she grew vegetables and flowers. Food to feed her body, flowers to feed her soul. Over the coming years she experimented to see what would survive in that rocky soil. ‘I tried growing all sorts of vegetables like cabbages and peas but the rodents ate them. The only things they wouldn’t touch were turnips and potatoes. Over the years I truly discovered the joy of turnips! I am now ever ready to promote the turnip,’ she enthused. ‘I discovered that turnips are a dual-purpose vegetable. You have the wonderful turnip greens, which are in fact the most nutritious of all vegetable greens and absolutely delicious, especially when young,’ she waxed. ‘No gourmet meal in the world is comparable to your first mouthful of fresh turnip greens after the long winter. And then you’ve got the bulb, which is also very good for you. Both of them can be cut up and dried, so that right through the winter you’ve got these wonderful vegetables. Actually I was waiting for the book One Hundred and Eight Ways to Cook Turnips but it never showed up,’ she joked.

She ate once a day at midday, as is the way with Buddhist nuns and monks. Her menu was simple, healthy and to ordinary palates excruciatingly monotonous. Every day she ate the same meal: rice, dhal (lentils) and vegetables, brewed up together in a pressure-cooker. ’My pressure cooker was my one luxury. It would have taken me hours to cook lentils at that altitude without it,’ she said. This meagre fare she supplemented with sour-dough bread (which she baked) and tsampa. Her only drink was ordinary tea with powdered milk. (Interestingly, the traditional tea made with churned butter and salt was one of the few Tibetan customs she did not like.) For desert she had a small piece of fruit. Manali was renowned for its apples and Tshering Dorje would deliver a box of them. ‘I’d eat half an apple a day and sometimes some dried apricot.’

For twelve years this was how it was. There was no variation, no culinary treats like cakes, chocolates, ice creams – the foods which most people turn to to relieve monotony, depression or hard work. She professed she did not mind and as she logically pointed out: ‘I couldn’t pop down to Sainsbury’s if I wanted anything anyway. Actually, I got so used to eating small quantities that when I left the cave people would laugh seeing me eat only half an apple, half a slice of toast, half a quantity of jam. Anything more seemed so wasteful and extravagant.’

And then there was the cold. That tremendous unremitting, penetrating cold that went on for month after month on end. In the valley below the temperature would regularly plunge to -35 degrees in winter. Up on that exposed mountain it was even bleaker. There were huge snowdrifts that piled up against her cave and howling winds to contend with too. Once again, Tenzin Palmo made light of it. ‘Just as I suspected, the cave proved to be much warmer than a house. The water offering bowls in front of my altar never froze over in the cave as they did in my house in Tayul Gompa. Even in my store-room, which was never heated, the water never froze. The thing about caves is that the colder it is on the outside the warmer it is on the inside and the warmer it is outside the cooler it is inside. Nobody believed this when I told them, but the yogis had told me and I trusted them,’ she insisted.

For all her avowed indifference, the cold must have been intense. She lit her stove only once a day at noon and then only to cook lunch. This meant in effect that when the sun went down she was left in her cave without any source of heat at all. Somehow she survived. ’Sure I was cold, but so what?’ she stated, almost defiantly, before adding in a somewhat conciliatory tone, ‘When you’re doing your practice you can’t keep jumping up to light the stove. Besides, if you are really concentrating you get hot anyway.’ And her comment begged the further question of how far she had got in her ability to raise the mystic heat, like Milarepa had done in his freezing cave all those centuries ago and the Togdens, who had practised drying wet sheets on their naked bodies on cold winter nights in Dalhousie. ‘Tumo wasn’t really my practice,’ was all she would say.

Endurance was one thing, however, comfort another. The pleasure of a hot bath, a fluffy towel, scented soap, a soft bed, crisp sheets, an easy chair, a clean lavatory – the soft touches that most women appreciate and need – she had none of. This desire for physical ease was said, by men, to be one of the biggest obstacles to women gaining Enlightenment. How could they withstand the rigours of isolated places necessary to spiritual progress, they argued, when by nature they wanted to curl up cat-like in front of a warm fire? In this, as in many things, Tenzin Palmo was to prove them wrong.

Her bath was a bucket. She washed sparingly, especially in winter when water was scarce and temperatures reduced body odours to zero. Her lavatory in summer was the great outdoors – her privacy was guaranteed. ‘In the winter I’d use a tin and later bury it.’ None of this bothered her. ‘To be honest I didn’t miss a flushing toilet or a hot shower because I’d already been so long without those things,’ she said.

Compounding her asceticisms was the total absence of any form of entertainment. Up in that cave she had no TV, no radio, no music, no novel, in fact no book which spoke of anything but religion. ‘There was no “luxury” I missed. Life in Dalhousie had prepared me admirably. I had everything I needed,’ she repeated.

Читать дальше