All this is news for blokes everywhere, I think: if the Neanderthals could get lucky with human females, there’s hope for us all. (One thing which blew my mind is that I have less Neanderthal in me than quite a few very brainy people. The professor guy who founded Knome, George Church, has three times more caveman in him than I do.)

Speaking of dead relatives, it also turns out that I share some DNA with the people killed in Pompeii when Mount Vesuvius blew its top in AD 79 (scientists took samples from the bodies in the ash, which is how they can tell). That means I’m also probably also descended from some of the survivors. Which makes a lot of sense, I suppose. If any of the Roman Osbournes drank anywhere near as much booze as I used to, they wouldn’t have even felt the burning lava. They could have just walked it off.

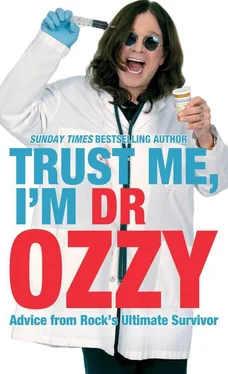

DR. OZZY’S INSANE BUT TRUE STORIES—

How the “Osbourne Identity” Was Unlocked

♦ In July 2010, a “phlebotomist”—whatever the fuck that is—took a sample of my blood and sent it to a lab in New Jersey.

♦ DNA was taken from my white blood cells, dissolved in a salt solution, and then sent off to Cofactor Genomics in St. Louis, Missouri.

♦ At Cofactor, my DNA was “chopped up” into 10 to 25 trillion pieces thanks to some heavy-duty shaking. After that, they spelled out all the chemical letters—in precise order—that make me the certifiable nutter I am.

♦ For the next 16 days, Cofactor used a photocopier-sized machine—which costs more than three Ferraris, so I’m told—to “read” my genome 13 times over and put it on a hard drive.

♦ The hard drive with “me” on it was sent to Knome, Inc., in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

♦ Knome compared the 6 billion letters in my genome with every other genome on the planet—to find why the fuck I’m still alive. Then they put all the findings on a little USB stick thing and presented it to me at home.

♦ While trying to understand what had just happened… my brain exploded.

Apart from the distant ancestor stuff—which seems more fun than useful, to be honest—Dr. Nathan told me things based on my DNA that only my wife or my personal assistant could ever have known. Trying to get him to say it in English was another matter. “There are some variants in your ‘ RNASE3 ’ gene that suggest you’re 240 times more likely than other people to have allergies, according to research,” he told me, for example.

Now, although those kind of odds are supposed to be quite unreliable—Dr. Nathan said they shouldn’t be trusted—they happen to be spot on in my case: I’m allergic to dust mites, and I get bad sinus infections. So who knows? Maybe the Osbourne snot gene might end up helping to find a cure for hay fever. I could think of worse ways to be remembered.

But that was just the beginning of what they found in the nose department when they were poking around in my DNA. “You also have some nonsense variants in nine of your odor receptor genes,” said Dr. Nathan.

“Eh?”

“Basically it means you might not be able to smell a few things—which isn’t all that unusual, because modern humans don’t have to sniff-out their dinner from two miles away, then go and club it to death. As the species has evolved, our sense of smell has become less sensitive.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: my old man used to claim that he didn’t have any sense of smell—or very little. We always thought he was taking the mickey. Me and my brother used to take it in turns to fart silently next to him, to try and catch him out. But he never fell for it—so maybe he was telling the truth, after all. Maybe it was all in his genes.

Another thing they found is that my body ain’t any good at metabolising coffee. (“You’re a slow acetylator of caffeine,” is how Dr. Nathan put it—according to Tony’s scribbled notes—“because of the way your NAT2 gene works.”) That explains a lot: I like the occasional blast of espresso, but all it takes is one shot, and my eyeballs feel like they’re gonna explode and I start shaking enough to register on the Richter scale.

Now I know why.

Bearing in mind what Dr. Nathan said about those odds figures being a bit dodgy, here are some of the other interesting things he told me: I’m 6.13 times more likely than the average person to have alcohol dependency or alcohol cravings (er… yeah); 1.31 times more likely to have a cocaine addiction; and 2.6 times more likely to have hallucinations while taking cannabis (makes sense, although I was usually loaded on so many different things at the same time, it was hard to know what was doing what). Meanwhile, I scored low on the genes associated with heroin addiction (I was never addicted to street heroin, ’cos it made me throw up—a terrible waste of booze—but I did get very addicted to morphine for a long time). I also scored low for nicotine addiction, which is interesting, ’cos cigarettes were the first thing I gave up when I got sober.

To be completely honest with you, some of the stuff Dr. Nathan told me seemed a bit on the bleedin’ obvious side. I mean, if I’d have been the bloke who forked out $3 billion for the first test, I’m not sure I would have been too impressed when the doc told me, “Well, Mr Osbourne, Your PTPN11 gene is normal-ish—so you don’t have Noonan Syndrome.”

“What’s Noonan Syndrome?” I asked.

“A type of dwarfism.”

“So I’m not a dwarf?”

“No.”

“Oh. That’s a relief then.”

And like I said before, there are lot of things they just don’t know yet. For example: Dr. Nathan says I have 300,000 completely new “spellings” in my DNA—“Of course I do, I’m fucking dyslexic!” I told him—but they don’t really know what that means. “One of those never-seen-before things we found in your genome was a regulatory segment in your ADH4 gene, which metabolises alcohol,” said Dr. Nathan. “It could make you more able to break down alcohol than the average person. Or less able.” Given that I used to drink four bottles of cognac a day, I’m not sure anyone needs a Harvard scientist to get to the bottom of that particular mystery.

“We also found new disruptions in your TTN and CLTCL1 genes,” the doc went on. “The first one might be associated with anything from deafness to Parkinsonianism, while we know that the second one can affect brain chemistry. If you wanted to find out more about your addictive behaviour, that might not be a bad place to start.”

If anything tells you how far all this stuff has to come, that pretty much sums it up for me: I mean, if there’s a gene for addictive behaviour, you’d have thought that mine would be written in pink neon with a ribbon and a bow on top.

Of all the parts of my genome that make up who I am—from my Pompei ancestors to my snotty nose and the fact I’m ready to blast through the ceiling after one cup of coffee—it was the last thing Dr. Nathan told me that really stuck in my mind. “You have two versions of a gene known as COMT ,” he said. “The first is often called the ‘warrior variant,’ and the second is known as the ‘worrier variant.’ A lot of people have one or the other—not both.” I suppose that makes me both a warrior and a worrier.

It reminded me of a time, years and years ago, when I was on holiday in Hawaii with this chick I knew. We were walking along a cliff-edge one day, and when I told her I was afraid of heights, she couldn’t believe it.

“I’m being serious,” I remember saying. “I’d get vertigo wearing your high heels.”

She just burst out laughing. I couldn’t work out what was so funny. Eventually, she said, “You don’t remember last night, do you? We were walking along this very same cliff and you ripped off your shirt and took a running jump. I don’t think you even looked to see if there were any rocks below. Luckily, you hit water. Then you wanted me to jump after you.”

Читать дальше